What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page revised in November 2011. |

Lepanto (Nafpaktos)

Lepanto (Nafpaktos)

Key dates: 1407 Venice bought the port of Lepanto 1499 Lepanto was conquered by the Turks 1571 Battle of Lepanto between a Christian fleet, gathered at the request of the Pope and led by Don John of Austria, and the Turkish fleet 1687 Lepanto was occupied by the Venetians but it was returned to the Turks by the peace of Karlowitz (1699) Lepanto (Nafpaktos) is located a few miles to the east of the Little Dardanelles the narrows which close the Gulf of Corinth. It was fortified by the Venetians and the Turks maintained the walls and the castle. The fortifications were made up of a castle on top of a little hill from which two walls went down to the sea. The sea-line was protected by maritime walls and three other walls were built at various levels on the hill between the maritime walls and the castle (see sketch here below) /___\ /_____\ /_______\ /_________\

The entrance to the harbour was protected by two towers and a large number of cannons. In 1570 the Turks attacked Cyprus and in August 1571 they conquered Famagusta, the last Venetian stronghold on the island. In the meantime at the request of Pope Pius V a large Christian fleet gathered at Messina in Sicily. Spain, Venice and the other Italian states were part of the alliance. The command was given to Don John of Austria, aged 26, natural son of Emperor Charles V. Venice moved the galleys located in Corfù and Candia to Messina. The commander of the Turkish fleet took advantage of this decision and from Negroponte (Euboea) moved around the Peloponnese and entered the Adriatic Sea where he attacked several towns belonging to Venice. He then moved to Lepanto to obtain new supplies.

The Christian fleet left Messina for the Ionian Islands and on October 7, 1571 it moved from the bay of Samos, in Cefalonia, towards Lepanto. It was in the interest of the Turks to avoid the battle or at least to fight in the vicinity of Lepanto to make use of the artillery of the fortress, but the Turkish commander underestimated the strength of the Christian fleet and thought that a victory would lead to the conquest of Candia and Corfù. What followed was the largest sea battle between oar fleets from the time of the Roman Empire. The ships were so many and in a limited space that the fight was decided by the Spanish swordsmen.

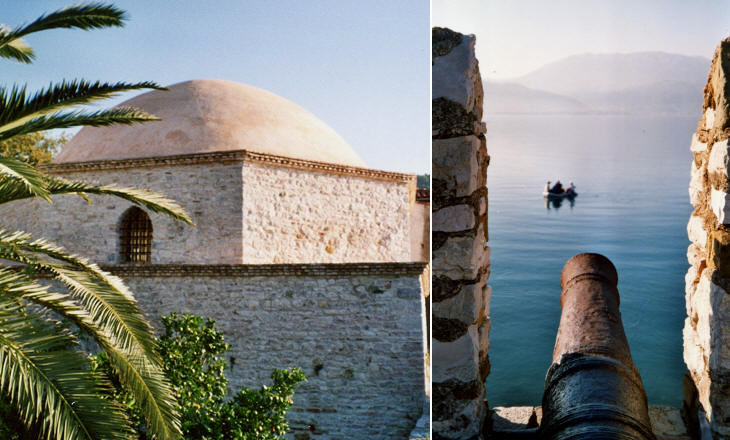

Both Venice and Spain have put inscriptions on the maritime walls of Lepanto to celebrate the battle. There is also a statue of Miguel de Cervantes, who fought and was seriously wounded in the battle. The tiny harbour has maintained (it is a miracle!) its ancient looks and even some symbols of the Turkish rule have been preserved.

The inner walls had only one point of passage located on the side of a tower. The walls are in general well kept but many of the buildings on the upper part of the hill have been abandoned and lie in ruins. Some of them show their Turkish origin.

The castle is surrounded by a beautiful pine wood. Little is little left of the barracks and of the other buildings which once were in the castle.

The views from the castle reward the effort made to get there. In particular the view over the harbour is very evocative of the past.

The victory of Lepanto was celebrated in all western Europe and in particular by Pope Pius V and his successor Pope Gregory XIII who wanted the event to be painted on a wall of the Vatican Palace. The red dot shows the castle of Lepanto. A 1900 map provides a more accurate view of where the battle took place.

The two fleets met near an islet which is today known as Oxia, but which at the time was called Isole Curzolari (the name included some smaller islets). For this reason the Venetians often called the fight as the battle of the Curzolari Islands. They celebrated it at the entrance of their Arsenale in Venice. The 1683 failed attempt by the Turks to conquer Vienna was regarded as a second Lepanto. Excerpts from Memorie Istoriografiche del Regno della Morea Riacquistato dall'armi della Sereniss. Repubblica di Venezia printed in Venice in 1692 and related to this page:

Introductory page on the Venetian Fortresses Pages of this section: On the Ionian Islands: Corfù (Kerkyra) Paxo (Paxi) Santa Maura (Lefkadas) Cefalonia (Kephallonia) Asso (Assos) Itaca (Ithaki) Zante (Zachintos) Cerigo (Kythera) On the mainland: Butrinto (Butrint) Parga Preveza and Azio (Aktion) Vonizza (Vonitsa) Lepanto (Nafpaktos) Atene (Athens) On Morea: Castel di Morea (Rio), Castel di Rumelia (Antirio) and Patrasso (Patra) Castel Tornese (Hlemoutsi) and Glarenza Navarino (Pilo) and Calamata Modon (Methoni) Corone (Koroni) Braccio di Maina, Zarnata, Passavà and Chielefà Mistrà Corinto (Korinthos) Argo (Argos) Napoli di Romania (Nafplio) Malvasia (Monemvassia) On the Aegean Sea: Negroponte (Chalki) Castelrosso (Karistos) Oreo Lemno (Limnos) Schiatto (Skiathos) Scopello (Skopelos) Alonisso Schiro (Skyros) Andro (Andros) Tino (Tinos) Micono (Mykonos) Siro (Syros) Egina (Aegina) Spezzia (Spetse) Paris (Paros) Antiparis (Andiparos) Nasso (Naxos) Serifo (Serifos) Sifno (Syphnos) Milo (Milos) Argentiera (Kimolos) Santorino (Thira) Folegandro (Folegandros) Stampalia (Astipalea) Candia (Kriti) You may refresh your knowledge of the history of Venice in the Levant by reading an abstract from the History of Venice by Thomas Salmon, published in 1754. The Italian text is accompanied by an English summary. Clickable Map of the Ionian and Aegean Seas with links to the Venetian fortresses and to other locations (opens in a separate window) |