What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page revised in July 2007. |

Corfu: the fortifications Corfu: the fortifications

Corfu played a key role in the expansion plans of the Kingdom of Naples in the XIth and XIIth centuries. First the Normans, then the Angevins occupied the island and used it as a base for their expeditions against Constantinople. At the end of the Angevin domination the Genoese occupied the island for a short period of time, but were expelled by the Venetian admiral Giovanni Miani. The lion banner of St Mark was hoisted over the city in May 1386 and in 1401 Ladislas, King of Naples formally sold the island to the Venetians.

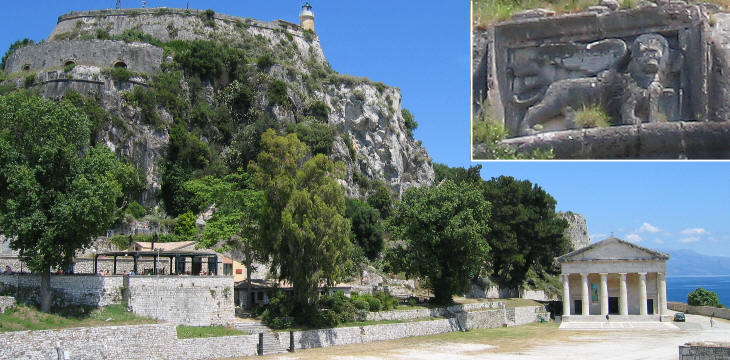

The Venetians strengthened the two fortresses which protected the small medieval town: the site of Corcyra, the ancient residence of King Alcinous who welcomed Ulysses and granted him safe passage to Ithaca, was located a few miles to the south of the medieval town.

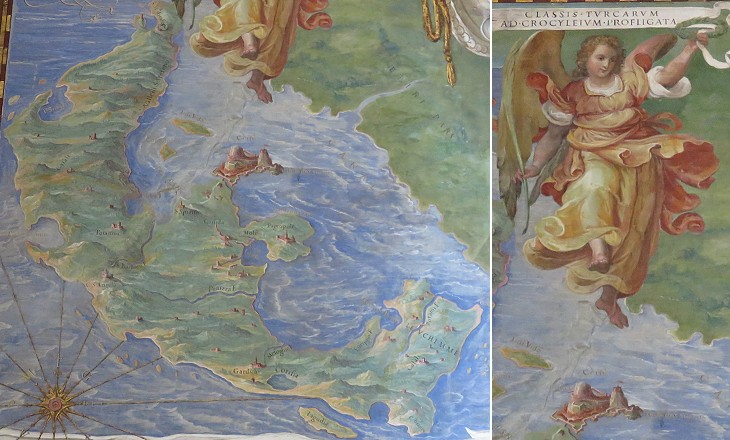

The Venetians called the island of Corfu Gateway to the Gulf as it controlled the maritime route giving access to the Adriatic Sea. Venice claimed her own sovereign rights over the whole sea which was also called Gulf of Venice. Corfu lies parallel to the shore of mainland Greece: the town is located in a central position from which it controls the whole channel between the island and the continent. In order to upgrade the fortifications to the development of cannon, the Venetians built some round bastions.

On account of its great strategic importance Corfu was subjected to attacks by the Ottomans who had established themselves on the mainland opposite the island. During the wars between Venice and the Ottoman Empire the inhabitants of Corfu fought by the side of the Venetians at Parga and at Butrinto in 1454 and at the Isthmus of Corinth and at Patras in 1462. In 1537 and 1716 the town of Corfu was besieged by the Turks.

In 1537 Khayr al Din Barbarossa (Red beard), a corsair who became admiral of the Ottoman fleet, attacked Corfu: the move was part of a larger plan conceived by Sultan Suleyman I. In alliance with King Francis I of France who was at war with Emperor Charles V he was preparing an invasion of southern Italy; in order to protect supplies to his army he needed to conquer Corfu. The decision to attack the island was made rather late: 25,000 Ottomans landed on August 25, but Khayr al Din soon realized he needed more troops and cannon: his forces were doubled by the Sultan, but the Venetians managed to check the enemy attacks until the Ottomans decided to raise the siege and leave the island.

In 1538 an allied Christian fleet was defeated by the Ottomans near Preveza: this event led the Venetian authorities to develop a major plan for ensuring Corfu could withstand a new Ottoman siege for a long time. Changes were radical: a large canal was dug between Castello della Campana and the island and two powerful bastions ensured the Venetian galleys could moor there without fear of being attacked by the enemy.

The plan developed by the Venetian engineers was not limited to the new bastions: almost all the inhabitants who lived in the old town were relocated in the burg beyond the canal. Walls surrounded the burg and a new fortress was built on a hill at its western end: this led over time to a change in naming the fortresses and the town: Castello della Campana and Castel da Mar were jointly called Old Fortress and the burg became known as the town and today it is referred to as the Old Town (this is how in 2007 UNESCO named the site when it included it in its World Heritage List).

The Old Fortress retains many reliefs and inscriptions of the Venetian rule: while in the past they were carelessly stored, now (2007) they have been properly displayed. During the British protectorate (1814-62) barracks were built on the site of the old cathedral and a new church was erected on a terrace at the foot of Castello della Campana: it was dedicated to St George (maybe in honour of King George IV). It has the shape of a Greek temple, although it is unlikely the ancient Greeks would have built a temple in such a position.

In 1669 the loss of Candia (Crete) made Corfu even more important for the protection of Venice. The second great siege of Corfu took place in 1716. That year Sultan Achmet II appeared in Butrinto opposite Corfu. On July 8, an Ottoman fleet carrying 30,000 men sailed across to Corfu from Butrinto and landed on the island where they established a beachhead. On the same day the Venetian fleet engaged the enemy fleet off the Channel of Corfu and gained an important victory as it delayed the Ottoman attack. On July 19 the Turks reached the hills to the west of the town and laid siege to it. The time had come for the New Fortress to show its strength.

The winged lions placed on the outer walls of the fortress do not have an aggressive appearance, with the exception of that on the Sea Gate: its open jaws show all the rage of the lion and the writer of this page mistook a car screeching for a loud roar. The Ottomans managed to conquer all the fortress outposts, but they found themselves under the fire of the fortress cannon; in addition Venetian ships could easily attack the left flank of their encampment. A sally by the defenders proved unable to dislodge the Ottomans, but led their commander to realize he was in a weak position: he then decided to make a final attempt to seize the fortress. On the night of August 18 the assault was launched and the Ottomans managed to seize a ravelin which projected from the fortress: from there they tried to climb the fortress: the fight went on for the whole night, but the defenders were able to check the enemy until a sally routed them: on the next day a furious thunderstorm (typical of the season) flooded the Ottoman encampment and that was the end of the siege. This victory over the Turks was attributed not only to the leadership of Count von Schulenburg, the commander of the defence, but also to the miraculous intervention of St. Spyridon. The Venetian Senate decided to honour von Schulenburg by dedicating a statue to him and in St. Spyridon's honour by donating to his church in Corfu a finely decorated lamp to be kept lit in perennial memory of the event.

The New Fortress is today (2007) open to the public with the exception of a small section occupied by the Greek Navy. The Venetians ruled the island for more than four centuries until 1797. Corfu and the other islands which belonged to the Republic of Venice (Paxi, Santamaura, Cefalonia, Itaca, Zante and Cerigo) went through a period of change until the 1815 Treaty of Paris established that they constituted a republic under British protection: this explains why some buildings of the New Fortress are dedicated to Victoria Regina.

Relations between the inhabitants of Corfu and the Venetian government were occasionally tense mainly due to tax reasons. Venice promoted the agricultural development of the island and in particular the cultivation of olive trees. To this policy Corfu owes its countless olive groves which are a feature of its landscape. The inhabitants took part in the naval battle at Lepanto (1571) to which Corfu sent 4 galleys and 1,500 men and they contributed to the defence of the town during the sieges.

The walls which surrounded the southern part of the town were in part pulled down to facilitate the development of new quarters. Some of the Venetian buildings in this area do not exist any longer or have been modified to serve different purposes; a theatre has become the Town Hall and barracks house state offices. The northern part of the town retains its old Venetian appearance: you may wish to visit it. Excerpts from Memorie Istoriografiche del Regno della Morea Riacquistato dall'armi della Sereniss. Repubblica di Venezia printed in Venice in 1692 and related to this page:

Introductory page on the Venetian Fortresses Pages of this section: On the Ionian Islands: Corfù (Kerkyra) Paxo (Paxi) Santa Maura (Lefkadas) Cefalonia (Kephallonia) Asso (Assos) Itaca (Ithaki) Zante (Zachintos) Cerigo (Kythera) On the mainland: Butrinto (Butrint) Parga Preveza and Azio (Aktion) Vonizza (Vonitsa) Lepanto (Nafpaktos) Atene (Athens) On Morea: Castel di Morea (Rio), Castel di Rumelia (Antirio) and Patrasso (Patra) Castel Tornese (Hlemoutsi) and Glarenza Navarino (Pilo) and Calamata Modon (Methoni) Corone (Koroni) Braccio di Maina, Zarnata, Passavà and Chielefà Mistrà Corinto (Korinthos) Argo (Argos) Napoli di Romania (Nafplio) Malvasia (Monemvassia) On the Aegean Sea: Negroponte (Chalki) Castelrosso (Karistos) Oreo Lemno (Limnos) Schiatto (Skiathos) Scopello (Skopelos) Alonisso Schiro (Skyros) Andro (Andros) Tino (Tinos) Micono (Mykonos) Siro (Syros) Egina (Aegina) Spezzia (Spetse) Paris (Paros) Antiparis (Andiparos) Nasso (Naxos) Serifo (Serifos) Sifno (Syphnos) Milo (Milos) Argentiera (Kimolos) Santorino (Thira) Folegandro (Folegandros) Stampalia (Astipalea) Candia (Kriti) You may refresh your knowledge of the history of Venice in the Levant by reading an abstract from the History of Venice by Thomas Salmon, published in 1754. The Italian text is accompanied by an English summary. Clickable Map of the Ionian and Aegean Seas with links to the Venetian fortresses and to other locations (opens in a separate window) |