What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page revised in December 2011. |

Cefalonia (Kephallonia) Cefalonia (Kephallonia)

Homer gave a summary of the ancient Greek world in his long catalogue of the participants in the War of Troy. Cefalonia and nearby Ithaca and Zante were part of that world, but a lesser one because Ulysses led a small fleet of twelve ships, whereas Nestor from Pilos went to war with ninety ships. The island was referred to also as Same or Samos, its port on the eastern coast (from where in 1571 the Christian fleet set sail to engage the Ottomans at Lepanto).

The history of Cefalonia was strictly associated with that of mainland Greece until the end of the XIth century when Robert Guiscard, King of Sicily and Southern Italy made an unsuccessful attempt to attack the Byzantine Empire. Eventually in 1185 a Norman fleet led by Margarito da Brindisi seized Cefalonia, Zante and Ithaca. The three islands became a personal possession of Margarito and at his death they were acquired by Riccardo Orsini, a member of an important Roman family, who married Margarito's daughter. After the 1204 conquest of Constantinople by the Frank knights of the Fourth Crusade, the Orsini managed to expand their possessions in mainland Greece by acquiring the town of Arta. The Orsini possessions were inherited by Leonardo I Tocco who belonged to a noble family of Neapolitan origin and who expanded them to include Ioanina. The Tocco managed to retain their possessions until Sultan Mehmet II, after having conquered Constantinople in 1453 and most of mainland Greece in the following years decided to expand the Ottoman Empire by invading Italy. In 1479 Sultan Mehmet II, in order to achieve his ultimate goal, seized Cefalonia and Zante to protect his back; he then captured Otranto, an important port in Apulia, which he planned to use as the starting point of a large campaign. In May 1481 however Sultan Mehmet II died, perhaps poisoned, and his successor Bayezit II, who was involved in a dynastic quarrel with his brother Cem, withdrew from Otranto.

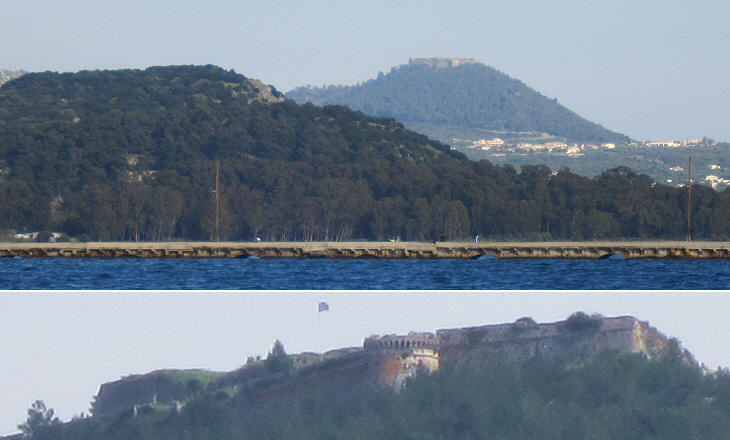

In 1500 the Venetians conquered the island with the help of Spanish troops. During their rule, the port of Samos lost importance in favour of the southern coast of the island where the Venetians promoted the production of wine and olive oil. A large fortress built on a hill had a commanding position which ensured this part of the island was protected. The fortress housed the residence of the governor and of other Venetian officers. Eventually the Venetians built a second large fortress at Asso to protect the inhabitants of the northern part of the island.

The hill was initially fortified by the Byzantines and after them by the Italian rulers of the island. It was named after a church dedicated to St. George. During the XVIth century the Venetians implemented a series of changes which almost completely transformed the old castle.

In 1453 the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans demonstrated that even the most imposing ancient walls could be breached by cannon. In the following decades a new development in the use of gunpowder led to the practice of digging tunnels to mine the walls of a fortification. Italian military architects reacted to these technological developments by designing large round bastions which could withstand the impact of cannon balls and of mines.

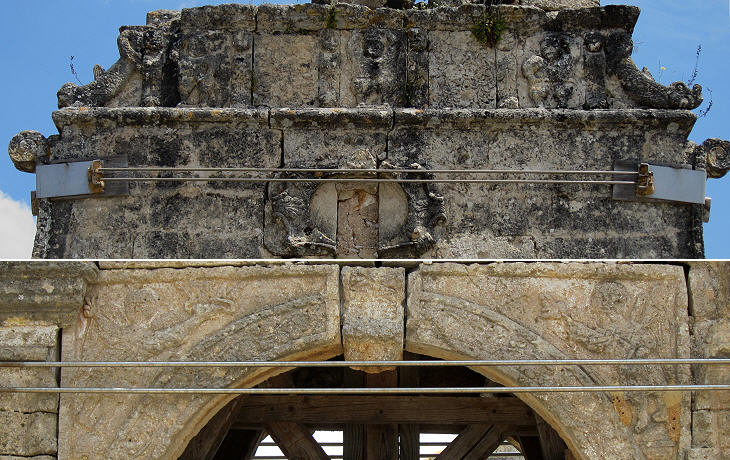

In 1545 the construction of three large round bastions was completed; military requirements were fulfilled without neglecting attention to elegance and proportions. In particular the western bastion was embellished with a very elaborate parapet.

Venetian governors of the island or commanders of the fortress placed their coats of arms on the bastions and on other facilities; a well was decorated with a corno dogale, the hat which was worn by the Doge, the highest magistrate of the Republic. It was called corno (horn) because of its shape; it was probably designed after Byzantine patterns or after the Phrygian cap, a symbol of liberty.

The protection granted by the fortress led to the development of Kastro (Castle), a small town outside the eastern bastion. Its main street lay between St. Theodore's and Panagia Evangelistria, the cathedral, which are the only remaining historical buildings of the town.

In 1953 what is called the Great Ionian Earthquake struck Cefalonia and Zante causing major destruction on the two islands. Evangelistria, the cathedral of the old town, is one of the very few buildings which did not collapse. The church was preceded by an imposing bell tower/grand portal. The modern cathedral (Mitropolis) of Argostoli is dedicated to Panagia Evangelistria (you may wish to see the sanctuary by the same name at Tinos).

The church is dated 1580, but the elaborate design and decoration of the bell tower suggests the latter was built at a later period; its structure resembles that of St. Charalambos' at Zante which was built in 1727.

The design of the church is rather plain and it shows the influence of Italian and Byzantine patterns. The detail of the hands holding the pole of a flag or a cross is rather unusual and it was perhaps designed by someone who had visited S. Maria di Aracoeli in Rome.

In 1636 a major earthquake struck Cefalonia; it did not have an impact on the huge bastions of the fortress, but it damaged many of the buildings of the nearby small town; many of its inhabitants moved to Argostoli, an excellent natural harbour from which oil, wine, raisins and currants were exported in large quantities. Eventually in 1757 Argostoli became the capital of the island.

Argostoli is located at the end of a long and narrow inlet which resembles a fjord. The very end of the inlet has shallow waters, but they were deep enough for the ships of the XVIIIth century. The extract from a 1692 Venetian book at the end of this page says that the whole Venetian Navy (Grossa Armata) could moor at Argostoli.

Cefalonia was a Venetian territory until 1797 when the Republic of Venice surrendered to Napoleon and its territories were shared between France and Austria. After Napoleon's fall, Cefalonia and the other Ionian islands became a British protectorate. For some time the local noble families of Venetian origin maintained a leading role in trade and administration. In books written in 1821 by Christian Miller, a British traveller, one can read about their standard of living: The stranger is surprised at the internal arrangements of private houses. Here we see mirrors, chandeliers, carpets, elegantly bound libraries of books with old French and Italian classics etc. Argostoli displays much wealth and mercantile spirit. The principal objects of trade are currants, oil, wine, cotton, silk, fowls, etc. It is interesting to see the wharf of Argostoli. The bustle here is very great; Argostoli has always had the largest shipping among the cities of the Ionian islands.

The Great Earthquake of 1953 razed Argostoli to the ground; the destruction had an enormous impact on the economy of the island and many inhabitants were forced to migrate. Eventually the beneficial effect of tourism reactivated the economy and Argostoli is today a very pleasant and quiet town (holidaymakers stay at a nearby resort on the other side of the peninsula of Argostoli).

From Christian Miller's book: The English have completed many new and useful works here. Of the best is Ponte Novo, a beautiful bridge built of stones similar to marble, over the neighbouring marshes. In its centre stands a pyramid with the inscription "To the Glory of the British Nation 1813". The inscription which was written also in Greek, Latin and Italian was erased during WWII.

The 1845 Murray Handbbok for Travellers in Greece dedicated a lengthy description to what seemed a mystery. Cephalonia presents a phenomenon apparently contrary to the order of nature; the water of the sea flowing into the land in currents or rivulets, which descend, and are lost in the bowels of the earth. This phenomenon occurs about a mile and a half from Argostoli, near the entrance of the harbour, where the shore is composed of freestone, and is low and cavernous, from the action of the waves. "The descending streams of salt water," says Dr. Davy, « are four in number; they flow with such rapidity, that an enterprising gentleman, an Englishman (Mr. Stevens), has erected (by permission of the Government) a grist-mill on one of them, with great success. The flow is constant, unless the mouths, through which the water enters, are obstructed by sea-weed. The phenomenon has been long known to the natives: familiar with it, it has excited no interest; they appear hardly to give it a thought. It is only recently that it has been brought to the knowledge of the English, within the last five or six years, and it is now become a subject of anxious inquiry and speculation.. It was eventually discovered by diluting red colour in the water that the chasms of Argostoli are linked to underground caves which are located at the opposite side of the island.

In May 1941, after the surrender of the Greek government, the country was partitioned into zones of occupation by Germany, Italy and Bulgaria. Cefalonia was part of the Italian zone of occupation and a division of 12,000 troops was stationed there. After Italy signed an armistice with the Allies on September 8, 1943 the Italians at Cefalonia were asked to surrender by the Germans. Upon their refusal, the Germans landed on the island and thanks to their complete air superiority after several days of combat they forced the Italians to surrender. Some 9,000 Italian soldiers and officers were not regarded as prisoners of war, but were summarily executed "for treason". Excerpts from Memorie Istoriografiche del Regno della Morea Riacquistato dall'armi della Sereniss. Repubblica di Venezia printed in Venice in 1692 and related to this page:

Introductory page on the Venetian Fortresses Pages of this section: On the Ionian Islands: Corfù (Kerkyra) Paxo (Paxi) Santa Maura (Lefkadas) Cefalonia (Kephallonia) Asso (Assos) Itaca (Ithaki) Zante (Zachintos) Cerigo (Kythera) On the mainland: Butrinto (Butrint) Parga Preveza and Azio (Aktion) Vonizza (Vonitsa) Lepanto (Nafpaktos) Atene (Athens) On Morea: Castel di Morea (Rio), Castel di Rumelia (Antirio) and Patrasso (Patra) Castel Tornese (Hlemoutsi) and Glarenza Navarino (Pilo) and Calamata Modon (Methoni) Corone (Koroni) Braccio di Maina, Zarnata, Passavà and Chielefà Mistrà Corinto (Korinthos) Argo (Argos) Napoli di Romania (Nafplio) Malvasia (Monemvassia) On the Aegean Sea: Negroponte (Chalki) Castelrosso (Karistos) Oreo Lemno (Limnos) Schiatto (Skiathos) Scopello (Skopelos) Alonisso Schiro (Skyros) Andro (Andros) Tino (Tinos) Micono (Mykonos) Siro (Syros) Egina (Aegina) Spezzia (Spetse) Paris (Paros) Antiparis (Andiparos) Nasso (Naxos) Serifo (Serifos) Sifno (Syphnos) Milo (Milos) Argentiera (Kimolos) Santorino (Thira) Folegandro (Folegandros) Stampalia (Astipalea) Candia (Kriti) You may refresh your knowledge of the history of Venice in the Levant by reading an abstract from the History of Venice by Thomas Salmon, published in 1754. The Italian text is accompanied by an English summary. Clickable Map of the Ionian and Aegean Seas with links to the Venetian fortresses and to other locations (opens in a separate window) |