What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page revised in January 2013. |

Part one - The Walls of Famagusta Part one - The Walls of Famagusta(detail of a Venetian Winged Lion in the fortifications of Famagusta) Introduction These pages deal with the surviving monuments of the French and Venetian rule over Cyprus (1192-1571). In 1187 Saladin the Great, Sultan of Egypt and Syria, conquered Jerusalem. Pope Gregory VIII issued a papal bull (Audita tremendi .. - Having heard the horrible news..) which called for a new crusade (the third one). In April 1191, King Richard the Lionheart, who was one of the leaders of the crusade, sailed from Messina in Sicily to reach the Holy Land. Some of his ships were wrecked on Cyprus and the crews were maltreated by the men of Isaac Comnenos, the local ruler who belonged to an important Byzantine family. Richard subsequently seized the island and captured Isaac who was released for a ransom many years later. In June King Richard set sail for Acre where he joined the Christians who had been besieging this port since 1189. Richard remained in the Holy Land until 1192, when, after having vainly attempted to restore the Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem, he reached an agreement with Saladin which allowed Christian pilgrims to safely access the Holy Sites. Richard sold the Kingdom of Cyprus to Guy de Lusignan, his vassal in Poitou, a region of France, who was the titular King of Jerusalem by right of marriage, as a compensation for having failed to reinstate him on the throne.

The Lusignans ruled Cyprus for nearly three centuries and they did so by introducing the feudal system existing in western Europe which meant serfage for the Greek population of the island. In the XIVth century the Lusignans had to face the growing influence of Venice and Genoa in the Levant and they usually sided with the Venetians; in 1373 the Genoese occupied Famagusta, the main port of the island. In 1453, the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople brought a new actor to the political scene of the Levant. Venice signed a peace treaty with Sultan Mehmet II in 1454, but the confrontation between the two powers was only postponed. War erupted in 1463 when the Ottomans seized Argo. In 1470 the Venetians lost Negroponte (Euboea), a key island in the Aegean Sea. The Lusignans borrowed significant amounts of money from Venetian bankers, in particular from the Cornaro (aka Corner) family, in order to reconquer Famagusta which they did in 1464. In 1468 King James II the Bastard, whose right to the throne was challenged by Louis Count of Savoy (the husband of James' legitimate half-sister Charlotte), decided to strengthen his ties with his bankers and Venice by marrying by proxy Caterina Cornaro, daughter of Ser Marco Cornaro. The Senate of Venice seized this opportunity for counterbalancing its losses in Greece. Caterina was named "Daughter of the Republic" and James was forced to sign a statement by which Caterina inherited the kingdom, should he die without leaving a heir. In 1473, a few months after the arrival of Caterina on Cyprus, James died at the age of 33 and Venice sent its fleet to Famagusta to protect the young widow, who was pregnant. Caterina, assisted by Venetian advisers, reigned over Cyprus on behalf of her infant son James III and after his death in her own right until 1489, when she was forced by her family to bequeath her kingdom to the Republic. Caterina returned to Venice where she was assigned the town of Asolo and here she set up a small court. The background of this page shows her in a drawing by Albert Durer, based on a painting by Giovanni Bellini. The Cornaro continued to be one of the richest Venetian families. You may wish to see the chapel Gian Lorenzo Bernini designed for Cardinal Federico Cornaro at S. Maria della Vittoria. Famagusta: the Walls

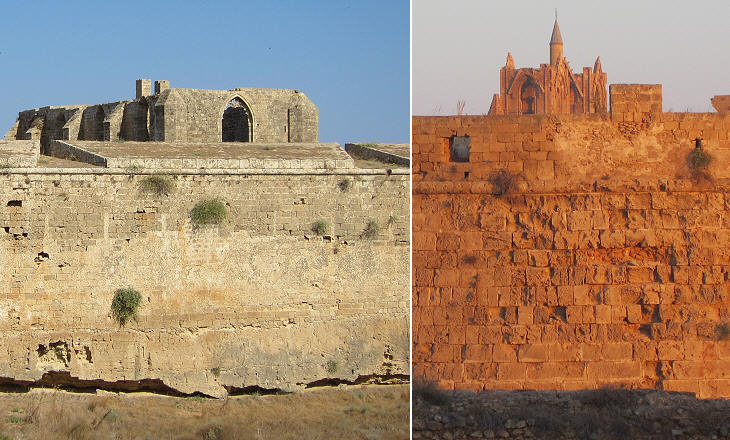

Famagusta rose to great importance as one of the main trading centres of the Levant after the loss of Acre in 1291. The Lusignans built a small fortress to protect the harbour.

Today it is known as Othello's castle. Othello, in the novel by Cinthio (Giovan Battista Giraldi) written in 1565 and in the tragedy by Shakespeare (Othello, the Moor of Venice) written in 1603, is a fictional Venetian commander of Arab/African origin, as the reference to Moor is not precise enough for determining his ethnical origin.

The Lusignans introduced Gothic architecture to Cyprus and the interior of the fortress has some large halls similar to those built by the Knights Hospitallers at Krak des Chevaliers and Marqab in Syria. In 1341 a member of the Lusignan family became King of Lesser Armenia, but the expansionistic policy of the Lusignans suffered a blow in 1373 when the Genoese seized Famagusta by surprise. Without their main port the Lusignans were unable to support their troops on the mainland and in 1375 the Mamelukes conquered the Kingdom of Lesser Armenia.

The Venetians soon realized that the fortress of Famagusta was not able to withstand an attack supported by cannon and they built round towers at its corners. They did not however spend too much effort on this fortress as they developed a major plan to turn the whole town into a state-of-the-art fortress.

From a legal viewpoint Cyprus was a kingdom, although it belonged to a Republic and for this reason the Lion of St. Mark, the symbol of Venice, was portrayed wearing a crown near a castle, a symbol of Cyprus or of Famagusta. Maintaining a legal identity with Cyprus was perhaps a way to limit papal interference on religious and trade matters. Famagusta in particular housed communities of many different Christian beliefs and it is likely that even some Muslim merchants lived in the town (see page three).

On crossing the drawbridge we ascended by a stone staircase to a defended passage leading to the sea at the end of which was a strong tower overlooking and completely commanding the port. The thickness of the walls and their domineering situation show this passage and tower to have been formerly of prodigious strength. William Turner - Journal of a Tour in the Levant - 1815. The fortress was linked to a bastion at one end of the harbour; in case of danger a chain was lifted between this bastion and the outer pier thus blocking the access to the harbour. A chain may seem a not very effective mean of defence, but chains were utilized even to close large stretches of water as on the Bosporus or at Nauplia.

The Venetians moved the government of the island from Nicosia to Famagusta and they concentrated their efforts on building new walls to protect the new capital. Massive round towers and a deep moat were among the key features of these walls; they were similar to those built at Rhodes by the Knights of St. John at approximately the same time. The walls which remain uninjured are immensely thick and strong and are fortified by a fosse (moat) in many parts hewn from the rock about eighty feet wide and twenty five deep into which the sea was formerly admitted but it is now dry. W. Turner - Journal.

Bastions having the shape of arrowheads were typical of Italian fortresses (aka star forts). Their design allowed the placement of guns in a side position from which they could fire on the enemies who were trying to climb the walls. In addition the guns protected a gate at the moat level from which the defenders could make sallies. The guns could not be hit by enemy artillery because of their sheltered location. A cavalier, an additional fortification on the top of the bastion was the last resort for its defenders (see a page on Valletta with details on its fortifications which included cavaliers).

Another feature of the defensive system was the ability to rapidly move cannon and other war machinery to the sites where they were needed.

For this reason even the highest points of the fortifications were made accessible to carriages and pack animals. The strategic objective of the fortifications of Famagusta was to gain time in order to allow the Venetian fleet to reach Famagusta and bring supplies and new troops.

According to the traditional account which portrays Sultan Selim II as a drunkard his decision to conquer Cyprus was caused by the desire to secure the supply of a particular wine which was produced there. In September 1570 Lala Mustafa Pacha, the Ottoman commander who led the failed siege of Borgo (on Malta) in 1565, with an army of 80,000 landed on the island and easily conquered Nicosia; he then convinced the garrison of Cirenes (today's Kyrenia/Girne) to surrender, thus ensuring his army had a good port for receiving supplies. On August 22, the Ottomans laid siege to Famagusta. The troops were highly motivated as they could see the many churches of the town where they expected to find gold and silver reliquaries and other booty.

After a few weeks Lala Mustafa invited Marcantonio Bragadin, Governor of Cyprus, to surrender. Upon his refusal he sent him a tin box containing the head of Niccolò Dandolo, the Venetian commander of Nicosia. Notwithstanding the gruesome warning Bragadin refused again as he knew that Lala Mustafa should demobilize part of his troops in the forthcoming weeks before the arrival of the winter season, as was customary in the Ottoman army. The defenders resisted for the whole winter and with the arrival of spring they had high hopes of receiving help from Venice. The Republic however sought an alliance with Philip II, King of Spain and Pope Pius V; this had a delaying impact on the gathering of a large fleet. In April the Ottomans resumed large scale assaults on the walls of Famagusta. Cambulat, Bey (governor) of Kilis, led his men in the assault of the south-eastern bastion which protected the Venetian arsenal. He is regarded as a hero and he is now buried in the bastion where he lost his life.

The walls had only one gate on the land side. It was preceded by a ravelin, an outwork in front of the gate. From there a bridge crossed the fosse to another ravelin on the counterscarp (the outer side of a ditch), of which no trace now remains. The attack on the Land Gate was especially severe as it was directed by Mustafa Pacha himself. The Ottomans seized the outer ravelin but the Venetians exploded a mine under it. On July 9 at the cost of enormous losses the Ottomans conquered the inner ravelin, but this too was blown up by the Venetians causing more than a thousand casualties.

The Ottomans repeated their attacks and the eldest son of Mustafa Pacha died in an assault which lasted 48 hours. At this point Mustafa Pacha, discouraged by the limited results achieved by his troops, stricken by the death of his son and ignoring the fact that the defendants had exhausted their gunpowder, offered extremely good terms for the surrender of Famagusta. The terms included: a) military honours; b) safe transfer of the troops to Candia; c) freedom for the rest of the population to remain or follow the troops. On August 1 the offer was accepted and the troops with some families embarked on Ottoman ships.

On August 5, Bragadin and his lieutenants were ready to formally hand over the keys of Famagusta to Mustafa Pacha. The meeting was accepted and at the beginning the Ottoman commander was very polite, but soon his mood changed and he ordered his guards to kill Bragadin's lieutenants. Bragadin had his nose and ears cut off. Two weeks later he was brought to the harbour and he was taunted: Look if you can see your fleet; look, great Christian, if you can see succour coming to Famagusta. He was flayed alive near the Governor's Palace. He was quartered and the skin filled with straw was sent to Constantinople to be shown around. The Ottoman commander became then known as Kara (black/dark, a reference to his cruelty) Lala Mustafa Pacha. A few years later the Venetians smuggled the skin of Bragadin to Venice where it is now buried in SS. Giovanni e Paolo. It is likely that Mustafa Pacha acted in this way in order to gloss over the fact that he had overestimated the remaining strength of the defendants (a mistake he had made on Malta too). Two months later at the battle of Lepanto in Greece the Christian fleet defeated the Ottoman one. In the fight Ali Pacha, the commander of the Ottoman fleet, was killed and his head was placed on a pike and shown around as a trophy, thus twinning the horror of Bragadin's death. See the other pages of this section: Famagusta - Main Churches Famagusta - Other Monuments Nicosia - Walls and Houses Nicosia - Churches and Mosques Cirenes (Kyrenia) An Excursion to Bellapais Larnaca  SEE THESE OTHER EXHIBITIONS (for a full list see my detailed list). |