What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page revised in October 2011. |

Napoli di Romania (Nauplia/Nafplio) Napoli di Romania (Nauplia/Nafplio)

If you came to this page directly, you might wish to read a page with an illustration of the old fortifications of Nauplia first. Palamidi

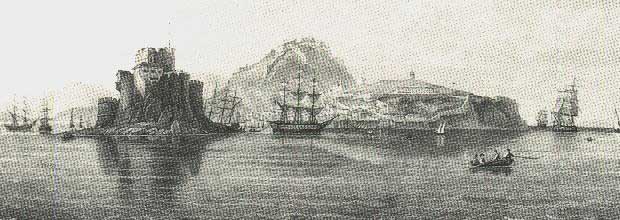

One of the reasons why in 1686 the Ottomans surrendered Nauplia was that the Venetians placed their cannon on Palamidi, a rocky hill to the east of the town. The Venetians were therefore aware that the control of Palamidi was essential to the protection of Nauplia; the western (towards the town) and southern (towards the sea) sides of Palamidi did not require major fortifications because of the nature of the ground.

The other sides of Palamidi did not enjoy the same natural protection and therefore the Venetians decided to build a complex of walls and bastions to prevent the enemy from reaching the top of the hill.

The Venetians decided to fortify the entire top of Palamidi, rather than concentrating their effort on its western end; the area covered by the new fortress was almost as large as that of the town. The original design by Antonio Giazich had the shape of a star, but the actual fortress ended up by having a very irregular aspect; it was made up of seven imposing bastions each of which was a small fortress; the main one, which housed a church dedicated to St. Andrew, has retained its original Venetian name, while the others are named after ancient Greek heroes.

The most impressive feature of Palamidi is St. Andrew's Bastion because of the 857 or so steps which allow direct access to the fortress from the town; the design of the bastion was such that it protected the upper section of the steps, while another section was protected by a vaulted passage. The new fortress was built in just three years between 1711 and 1714.

The administrative/military organization of the Venetian Republic was rather complex and it was based on a distribution of responsibilities; the navy was commanded by a Provveditor da Mar who usually resided on Corfu; he was assisted by a council of naval officers; the Peloponnese (or Morea) was placed under the responsibility of a separate governor; other officers were responsible for monitoring the expenses incurred by the navy and the garrisons of the fortresses. The commander of a fortress was often appointed on the basis of agreements reached in Venice among the members of the most important families; these agreements did not necessarily consider the actual military experience and leadership of the appointee. The shortcomings of such a management system showed all their negative impact when the Ottomans waged war on Venice with the primary objective of reconquering Morea.

In September 1714, at the end of a long career, Alessandro Bon was appointed governor of Morea; he reported to the Senate that he found that too many fortresses were built by his predecessors, including a major one at Modon without giving proper consideration to the need of garrisoning them appropriately and ensuring adequate supply of ammunition. The complex of fortifications of Nauplia (Palamidi, Acronauplia, Bourtzi and the city walls) would have required a garrison of at least five times that which appears in Venetian accounting records (1279 men).

The Ottoman declaration of war occurred in December 1714, but the actual Ottoman campaign started only in June of the following year. The Venetian Senate vainly called for help from Austria; Emperor Charles VI was too busy in consolidating the territorial gains he made as a result of the Spanish Succession War and he was not interested in opening a new front. The Senate hoped to appease the enemy calling for negotiations, but with no result because the Sultan regarded the occupation of Morea as unlawful. Overall the Venetian governing bodies were unable to develop an effective political or military strategy to cope with the impending war. The Ottomans seized Tinos, Corinth and Aegina easily; on July 9 1715 they laid siege to Nauplia and in less than two weeks they conquered it because the Venetian mercenaries were unable to effectively control all the defensive lines. The Ottomans noticed that the maritime walls of the town were almost unguarded and they managed to set foot on the wharf of the harbour from where they entered the town and opened the main gate. The Venetians retreated in disarray inside Palamidi, but were unable to check the assailants. Alessandro Bon was wounded and died a few days later while he was being transferred to Constantinople to be paraded in front of the Sultan. Under these circumstances the Provveditor da Mar chose not to come to the rescue of Nauplia and of the other fortresses under attack and concentrated all his forces in the defence of Corfu.

Before the construction of the fortress on Palamidi, the Venetians built a bastion to complete the fortifications of Acronauplia and to protect the new entrance to the town; the gate was reconstructed in recent years and the lengthy inscription celebrating Francesco Morosini (who eventually died at Nauplia in 1694) was placed on a side wall. The town was protected by the fortress of Acronauplia and on the other sides by walls (now lost) and by a moat.

The Town

Modern Nauplia retains the grid of orthogonal streets which was designed by the Venetians when they relocated the inhabitants of Acronauplia to the new town.

The heart of the new town was a rectangular square where a large warehouse was located; today the building houses a very interesting museum with exhibits from ancient Tiryns, which was located just a few miles north of Nauplia.

The period between 1453 (Fall of Constantinople and end of the Byzantine Empire) and 1821 (Rising of the Peloponnese which marked the beginning of the Struggle for Independence) was regarded as the Dark Age of Greece until recent years. Today Greek authorities pay more attention to the memories of this period and one of the many winged lions with which the Venetians decorated Nauplia has been placed in the main square; other similar reliefs (such as that which can be seen in the background of this page) and Venetian coats of arms are for the time being (2011) stored in an old building.

One of the reasons behind the poor showing of the Venetians in 1715 is that they lacked the support of the Greek population; in particular the Orthodox clergy were hostile to them, because, although somewhat reluctantly, Venetian authorities favoured the Roman Catholic Church. As stated by a Patriarch of Constantinople (for the Greeks) it was better the Sultan’s turban than the cardinal’s hat.

The war between the Ottomans and Venice ended in 1718 with the Peace of Passarowitz and after a failed Ottoman attempt to seize Corfu; it was the last war between these two powers. Thus Nauplia became a sleepy provincial town with little military importance; Palamidi was mainly used as a prison.

In 1822 Theodore Kolokotronis, one the leaders of the Greek uprising, managed to conquer Nauplia which in 1828 became the see of a provisional Greek government chaired by Giovanni Capodistria (who later adopted the Greek spelling Kapodistrias), a noble from Corfu who studied medicine at Padua. He was supported by Russia because for many years he had been a senior diplomat of Tsar Alexander I.

While in many parts of the Peloponnese all mosques were torn down, this did not occur in Nauplia because they were turned into buildings housing institutions of the newly born state. Their minarets however were pulled down.

In 1831 Kapodistrias was assassinated while entering the church of Agios Spiridionis, a somewhat ironical coincidence as St. Spyridon is the patron saint of the inhabitants of Corfu. He was killed by members of the Mavromichalis family, in retaliation for the arrest of their leader; the Mavromichalis were the de facto rulers of the Maina (Mani) peninsula and they resented Kapodistrias' attempts to impose modern laws and practices in their fiefdom.

In 1832 an agreement between Russia, France and Great Britain "appointed" Otto, a Bavarian prince, as the first king of Greece; the young king (he was 18) arrived at Nauplia with a small retinue of German advisors and 3,500 troops; he decided almost immediately to move the capital from Nauplia to Athens, which at the time was a minor town of some 5,000 inhabitants. The actual move occurred in 1834 and Nauplia returned to being a sleepy provincial town before becoming an important tourist location for its beaches and as the starting point for visiting Mycenae and Epidaurus.

Return to page one. Excerpts from Memorie Istoriografiche del Regno della Morea Riacquistato dall'armi della Sereniss. Repubblica di Venezia printed in Venice in 1692 and related to this page:

Introductory page on the Venetian Fortresses Pages of this section: On the Ionian Islands: Corfù (Kerkyra) Paxo (Paxi) Santa Maura (Lefkadas) Cefalonia (Kephallonia) Asso (Assos) Itaca (Ithaki) Zante (Zachintos) Cerigo (Kythera) On the mainland: Butrinto (Butrint) Parga Preveza and Azio (Aktion) Vonizza (Vonitsa) Lepanto (Nafpaktos) Atene (Athens) On Morea: Castel di Morea (Rio), Castel di Rumelia (Antirio) and Patrasso (Patra) Castel Tornese (Hlemoutsi) and Glarenza Navarino (Pilo) and Calamata Modon (Methoni) Corone (Koroni) Braccio di Maina, Zarnata, Passavà and Chielefà Mistrà Corinto (Korinthos) Argo (Argos) Napoli di Romania (Nafplio) Malvasia (Monemvassia) On the Aegean Sea: Negroponte (Chalki) Castelrosso (Karistos) Oreo Lemno (Limnos) Schiatto (Skiathos) Scopello (Skopelos) Alonisso Schiro (Skyros) Andro (Andros) Tino (Tinos) Micono (Mykonos) Siro (Syros) Egina (Aegina) Spezzia (Spetse) Paris (Paros) Antiparis (Andiparos) Nasso (Naxos) Serifo (Serifos) Sifno (Syphnos) Milo (Milos) Argentiera (Kimolos) Santorino (Thira) Folegandro (Folegandros) Stampalia (Astipalea) Candia (Kriti) You may refresh your knowledge of the history of Venice in the Levant by reading an abstract from the History of Venice by Thomas Salmon, published in 1754. The Italian text is accompanied by an English summary. Clickable Map of the Ionian and Aegean Seas with links to the Venetian fortresses and to other locations (opens in a separate window) |