What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page revised in August 2015. |

- Safavid Isfahan - Royal Palaces - Safavid Isfahan - Royal Palaces(dome of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque at Isfahan) You may wish to read an introduction to this section first.

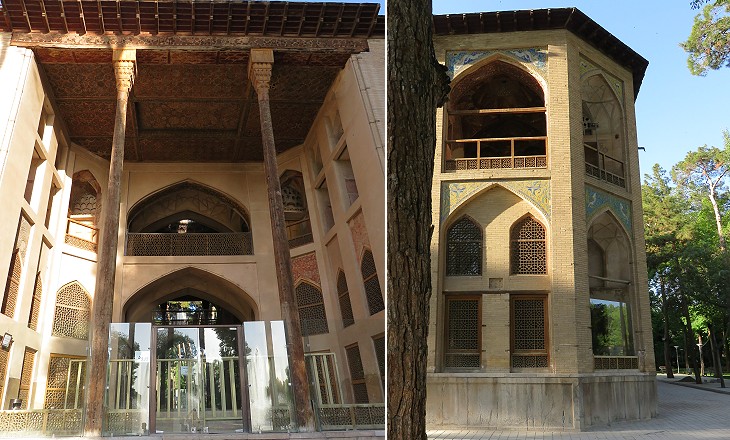

In a garden formerly beautiful but semi-barren and untidy now, on a pavement of slabs which are no longer on the level with one another, stands the Palace of the Twenty Columns, called of "the forty columns," probably because the twenty existing ones are reflected as in a mirror in a long rectangular tank of water. Distance lends much enchantment to everything in Persia, and such is the case even in this palace. Henry Savage Landor - Across Coveted lands - 1902. He was an English painter, explorer, writer and anthropologist (1865-1924). Chehel Sotun is one of several palaces/pavilions which made up the royal residence of the Safavid kings. The entrance to the compound was Ali Qapu in Naqsh-e Jahan, the main square of Isfahan. Chehel Sotun was built by Shah Abbas II who ruled over Persia in 1642-66.

The twenty octagonal columns of the open-air hall were once inlaid with Venetian mirrors, and still display bases of four grinning lions carved in stone. But, on getting near them, one finds that the bases are chipped off and damaged and the glass almost all gone. Henry Savage Landor The palace and the garden were restored extensively in 1977-80. Most of the great wooden columns of the large porch were removed from their bases, sawn in half and their central core hollowed out to receive and hide steel reinforcing rods. In 2011 UNESCO added Chehel Sotun and eight other Persian gardens to their list of World Heritage Sites. You may wish to see the garden of Cyrus the Great at Pasargadae, Bagh-e Dolatabad at Yazd, Bagh-e Eram at Shiraz and Bagh-e Fin at Kashan.

The Palace is divided into two sections, the open throne hall and the picture hall behind it. (..) The end central receptacle or niche is gaudily ornamented with Venetian looking-glasses cut in small triangles. Henry Savage Landor The talar was entirely rebuilt in 1706 after a fire. It is possible that its glass decoration was influenced by Galerie des Glaces (Hall of Mirrors), the central gallery of the Palace of Versailles which had been completed in 1684. In turn the glass decoration of Chehel Sotun influenced that of many other Persian open air halls built in the XIXth century such as Naranjestan at Shiraz and the Shah Palace at Teheran. The Governor held a reception which brought the Chehel Sotun to life again, transforming it from a stale summerhouse into the stately pleasure-dome it originally was. Spread with carpets, lit with pyramids of lamps, and filled with several hundred people, the verandah looked enormous; (..) the glass niche at the back, glittering through its gold filigree, seemed infinitely distant. Robert Byron - The Road to Oxiana - Macmillan 1937 (piece written in 1934).

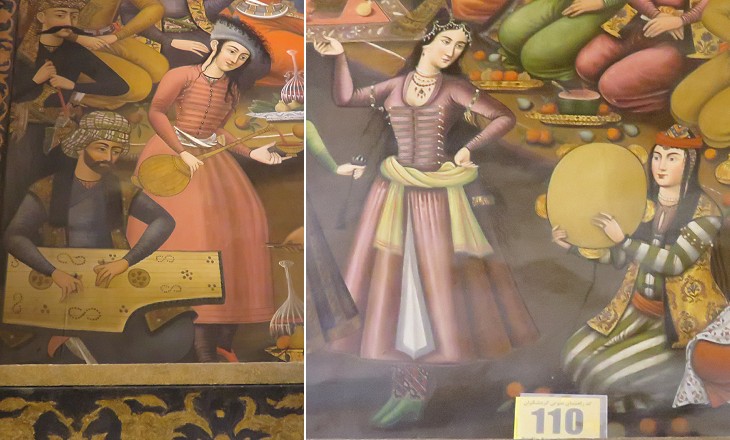

The hall behind the "talar" strikes the viewer because of its large paintings depicting Safavid Shas defeating their enemies or entertaining their guests. Robert Byron dismissed them as languid Safavid frescoes which give the world a false idea of Persian art and sentiment. The subjects chosen for the decoration of the room recall the reliefs at Persepolis and Bishapur where Achaemenid and Sassanid rulers were portrayed on the battlefield or receiving embassies. Shah Abbas II had himself and his predecessors portrayed in this hall, but in the XVIIIth century two paintings were replaced by others portraying shahs who came to power after the Safavids.

The inner hall must have been a magnificent room in its more flourishing days. It is now used as a storeroom for banners, furniture, swords, and spears, piled everywhere on the floor and against the walls. One cannot see very well what the lower portion of the walls is like, owing to the quantity of things amassed all round, and so covered with dust as not to invite removal or even touch. Henry Savage Landor An extensive restoration which included removing patches of later decoration has brought new life to the paintings. They offer an interesting insight into the Safavid court. The Shah and his guest have their meal on a low table which is still used in modern Iran and in Uzbekistan. Shah Tahmasp has a short beard but all the members of the Persian court are clean shaven and wear long moustaches (as reported by Pietro della Valle, an Italian traveller who visited Isfahan in 1616). The number of feathers on the turban was a sign of rank.

Finally, to the left of the front door we have pictorially the most pleasing of the whole series, another scene of feasting, with the youthful figure of Shah Abbas II, a man of great pluck, but unfortunately given to drunkenness. (..) In the foreground a most graceful dancing-girl, with a peculiar waistband, and flying locks of hair. The artist has very faithfully depicted the voluptuous twist of her waist, much appreciated by Persians in dancing, and he has also managed to infuse considerable character into the musicians, the guitar man and the tambourine figure to the right. Henry Savage Landor Drunkenness was not unusual among Persian rulers and their Ottoman rivals. The pleasures of drinking wine were chanted by Persian poets beginning from the Xth century and the region of Shiraz was known for its wines which European travellers found excellent. At the reception attended by Byron At the end of the room was a cold buffet, which dispensed red cup from large bowls. Being composed of three parts arak (anise liquor) and one Julfa wine, it was not so innocent as it looked.

In 1608 Shah Abbas I received a Bible from Pope Paul V and appreciated its illustrations. Pietro della Valle found out that Italian paintings were sold at the bazaar.

Dutch painters were invited to Isfahan and Shah Abbas II studied drawing with them. Muslim painters featured western elements in their works, so it is no surprise to find personages in European clothes at Chehel Sotun.

Hasht Behesht is the only other remaining pavilion of the royal compound. Its name is a reference to its structure having four large corner rooms on each floor. Similar to Chehel Sotun it was surrounded by a garden (Bagh-e Bulbul = Garden of Nightingales). It is situated near Madar Shah Medrese and Chahar Bagh, the large alley which links Si-o-Seh Bridge to the city centre.

Hasht Behesht was built some twenty years after Chehel Sotun by Shah Suleiman (another heavy drinker). It is a small building with large openings, maybe it was used as the scenery for feasts which took place in the gardens. Suleiman Shah spent most of his life inside the royal compound and left the running of state affairs to the women of the harem and to their eunuchs. The palace has lost most of its original decoration with the exception of that of the Golden Room, one of the corner rooms. Today it is part of a public park where I happen to meet Iranians exercising before going to work (it opens in another window).

Other Isfahan pages: Seljuk Isfahan Shah Abbas Mosque Other Mosques Naqsh-e Jahan Southern Quarters Introduction Achaemenid Pasargadae and Persepolis Sassanid Bishapur Achaemenid Tombs and Sassanid Reliefs near Persepolis Zoroastrian survivors Seljuk small towns (Ardestan, Zavareh and Abarquh) XIVth century Yazd XVIIIth century Shiraz Qajar Kashan Post Scriptum On the Road An excursion to Abyaneh Persian Roses People of Iran     |