What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in May 2014. |

- Persepolis - the Palaces - Persepolis - the Palaces(dome of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque at Isfahan) You may wish to read an introduction to this section or to Persepolis first.

Alexander the Great seized Persepolis in January 330 BC. Four months later the monumental part of the city was burned. Archaeologists have excavated a layer of ashes of up to ten feet. Historians disagree on the causes of the fire: accidental or ordered by Alexander as a revenge for not having been acknowledged as the new Achaemenid king after the killing of Darius III by one of his satraps. Others say he did it in retaliation for the burning of the Acropolis of Athens by Xerxes in 480 BC.

There are still things to be said about Persepolis. In its prime, when the walls were mud and the roofs wood, it may have looked rather shoddy - rather as it would look, in fact, if reconstructed at Hollywood. Today, at least, it is not shoddy. Only the stone has survived. Stone worked with such opulence and precision has great splendour, whatever one may think of the forms employed on it. Robert Byron - The Road to Oxiana - 1937 - Macmillan & Co. (piece written in March 1934).

Persepolis was neither the largest city of the empire, nor its major economic centre. The decoration of its palaces basically had only one purpose: the depiction of the ceremonies which took place there. It has some conventional features such as the king having a gigantic size, but otherwise it looks very accurate. The king was portrayed with symbols of his power (a sceptre) and of his divine status (a fly-whisk and a parasol) which have survived until the present day. You may wish to see the use of parasols at an Eritrean celebration of Michaelmas and by the Popes who were followed by attendants with flabelli, large fly-whisks (until the 1960s).

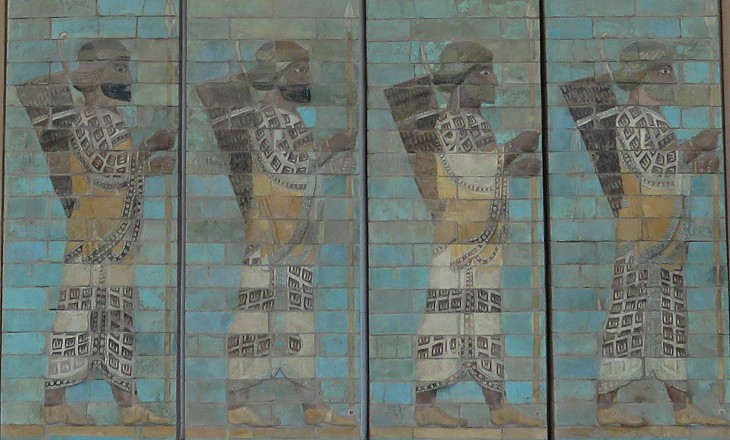

The decorations of the entrances to the palaces and of the platform supporting the Apadana convey the message that the power of the king rests on the shoulders of his satraps (the governors of the provinces) and is protected by his army. The soldiers are never portrayed in a fight, but always as if parading in front of their king.

The Achaemenid army greatly relied on archers. An anecdote reported by Herodotus says that when the Persians discharged their arrows at the Battle of Thermopylae, they obscured the light of the sun. The skill of the Achaemenid archers passed on to the Parthians and the Sassanids.

Apollo and Artemis were very often portrayed by Greek sculptors with the bow they used to hunt. Eros threw arrows to make people fall in love. At war however the Greeks (and the Macedonians of Alexander the Great) were mainly equipped with spears, spikes and a short sword. Roman legionaries used javelins, a short sword and a dagger. Trajan's Column is a monument similar to the Apadana in the sense that it accurately depicts the Romans at war, as the Apadana depicts the Persians celebrating their king.

The Apadana Staircase, similar to the Great Staircase, was designed to allow a solemn access to the audience hall. Its decoration, in addition to soldiers, included cypress trees and two large reliefs portraying a fight between a lion and a bull. This subject is depicted at many other places in the Apadana and other palaces. The prevalent opinion is that it had an astronomical significance, the lion representing the constellation Leo and the bull the constellation Taurus. They would indicate the spring equinox, a major festivity and the beginning of the new year in many ancient civilizations. Cypress trees were planted near Zoroastrian temples. At that time Zoroastrianism was a well established religion, but it cannot be said with certainty that the Achaemenid kings were among its followers.

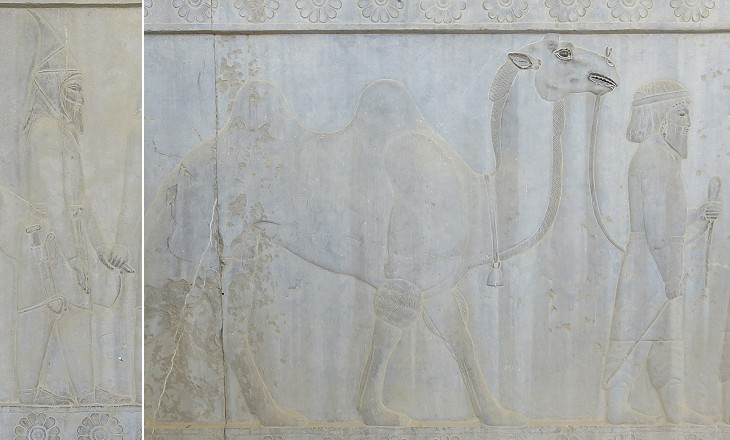

The largest panel of the Apadana staircase depicts a procession of people carrying gifts (clothes, vases, jewels, animals, but not weapons). Archaeologists have studied it extensively and have identified delegations from between 23 and 28 countries which were part of the Achaemenid Empire at the time of Darius. Lydia was one of the westernmost provinces of the empire (see a page on Sardis, its former capital). Cilicia was a key province because of its location between Anatolia and Mesopotamia.

The reliefs were carved on a stone of extreme hardness. They must have required an enormous amount of careful work, but by and large they have escaped the injury of time. They have a very unusual metal appearance; according to Robert Byron they are slick as an aluminium saucepan.

The fluting of the Apadana columns suggests workmen from Ionia made them (see the Temple to Apollo at Didyma in Ionia), while their bases recall Egyptian patterns. The central hall had 36 columns and it was surrounded by three porticoes of 12 columns each. The beams placed on the columns and the roof were mainly made of cedars of Lebanon, a light weight wood. The beams and the roof were painted.

This palace adjoined the Apadana and the king moved from it to meet the delegations. Xerxes added a staircase on its southern side. The decoration of the staircase is very similar to that of the Apadana, but it has a long inscription in three languages at its centre in which Xerxes states that he has completed the building initiated by his father.

The image used as background for this page shows a relief portraying a member of the court of Darius the Great at the National Museum of Tehran. Return to page one. Introduction Sassanid Bishapur Achaemenid Tombs and Sassanid Reliefs near Persepolis Zoroastrian survivors Seljuk small towns (Ardestan, Zavareh and Abarquh) Seljuk Isfahan XIVth century Yazd Safavid Isfahan XVIIIth century Shiraz Qajar Kashan Post Scriptum On the Road An excursion to Abyaneh Persian Roses People of Iran     |