What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in June 2014. |

- Zoroastrian Survivors - Zoroastrian Survivors(dome of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque at Isfahan) You may wish to read an introduction to this section first.

The Sassanid kings who ruled Persia from 228 AD to the Arab invasion in 633-651 endorsed Zoroastrianism as the sole religion of their empire. The long confrontation between Sassanids and Byzantines was to some extent a religious war between Zoroastrians and Christians. In 614 Sassanid King Khosrau II seized Jerusalem and carried away the True Cross from the Holy Sepulchre to Ctesiphon, his capital. He conquered Syria, Palestine and Egypt profiting from the rifts among different Christian creeds, but his attempts to impose Zoroastrianism facilitated the reaction of Byzantine Emperor Heraclius. The latter won back the lost territories by 628 and recovered the True Cross (you may wish to see a fresco by Piero della Francesca celebrating Heraclius' victory - it opens in another window).

According to Muslim sources King Khosrau II was invited to convert to Islam and refused (most likely right before he was overthrown and assassinated in 628 on the orders of one of his sons). In the following years the Sassanid Empire was torn apart by dynastic conflicts and was unable to oppose the Arab invasion of Mesopotamia in 633. A second campaign in 642-651 led to the Arab conquest of the whole of Persia. According to the Prophet's teachings Jews and Christians, the "People of the Book", were allowed to practice their own religion in countries conquered by the Muslims, as long as they did so in private. Zoroastrians instead were regarded as pagans and their religion was to be eradicated.

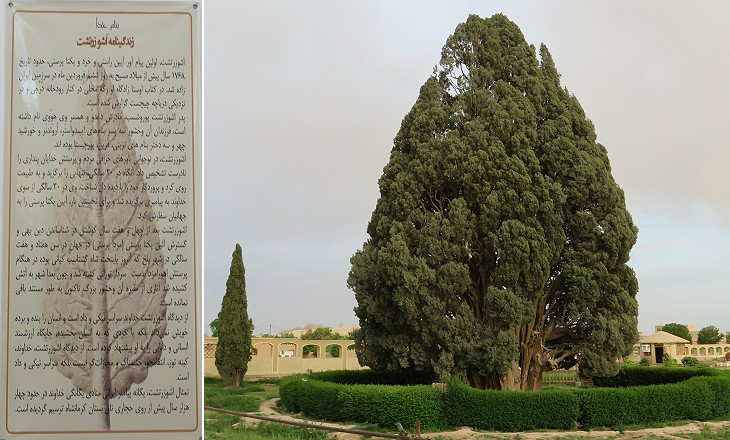

Zoroastrians used to plant cypress trees near their temples in memory of one planted by Zoroaster, the founder of their faith. A gigantic cypress said to be 4,000 year old at Abarquh, along the desert road leading to Yazd, is most likely an indication that a Zoroastrian temple existed there. Reliefs depicting cypress trees decorated the Apadana Staircase at Persepolis. The iconography which characterizes current Zoroastrian sites and rites is very much linked to the Achaemenid or (First Persian) Empire, rather than to the Sassanid one. According to a traditional account reported by Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, Zoroaster lived in the early VIth century BC when that empire was founded. Today this dating is challenged and Zoroastrian texts are believed to have been written at an earlier time.

Two large deserts cover the eastern part of the Persian tableland and for some time they formed a natural barrier to Muslim expansion. Some Zoroastrian communities living in towns near these deserts, such as Yazd, were eventually allowed to practice their faith, as long as they paid a special tax. Approaching Yazd in the early morning, after another all-night journey, we met a Zoroastrian funeral. The bearers were dressed in white turbans and long white coats; the body in a loose white pall. They were carrying it to a tower of silence on a hill some way off, a plain circular wall about fifteen feet high. Robert Byron - The Road to Oxiana - Macmillan 1937 (piece written in March 1934). Almost all of the Achaemenid kings were buried in imposing tombs, but the same cannot be said for the Sassanid ones. It is therefore believed that the Zoroastrian practice of disposing of dead bodies by leaving them to the action of scavenging birds and to the calcination effects of the sun was adopted during the Sassanid period or immediately after.

When Robert Byron saw the Zoroastrian funeral the task of depriving dead bodies of their flesh was carried out by domesticated vultures. The bones were collected in an ossuary pit at the centre of a circular building. The use of towers of silence was introduced in the XVIth century and they were located far away from towns. This practice was gradually discontinued and was eventually forbidden in the 1970s. It has been replaced by cremation or by a form of burial which prevents the dead body from being in contact with the ground.

Many Sassanid supporters fled to the desert mountains east of Yazd where they fought a sort of guerrilla warfare against the Arab invaders. According to tradition Princess Nikbanou, a daughter of the last Sassanid king, was about to be taken prisoner by the Arabs when she prayed to Ahuramazda, the Zoroastrian God of Good, to protect her. The mountain opened up and she disappeared into it (for a similar account relating to St. Techla see my page on Maaloula). Every year in June, Zoroastrians gather at a shrine in the remote location where the miracle occurred.

The Zoroastrian gathering place is located in a very hostile environment. Even today, notwithstanding a modern road, not a single house or evidence of human presence is in sight for miles and miles. For centuries a tall plane tree hidden by a rock was the only sign of the shrine. It stood near a small spring. The falling of its drops (believed to be tears in memory of Princess Nikbanou) has given the name to the location.

A series of open air terraces have been built near a modern shrine which incorporates part of the plane tree trunk. Fire in today's Zoroastrianism is regarded as a symbol of purity and spiritual ascension. Its worship might have started for the practical need of providing an easy source of fire to the community, as it most likely started in Rome with the creation of Vestali, a body of priestesses in charge of keeping a sacred fire alight. The image used as background for this page shows a panel depicting a burning fire in the Zoroastrian Museum of Yazd.

A number of Zoroastrians fled to north-western India in the VIIIth century. Zoroastrian communities in India and Persia were separated until the XIXth century. Persian Zoroastrians received help from the Society for the Amelioration of the Conditions of the Zoroastrians in Persia which was founded in Bombay (Mumbai) in 1834. Eventually some Persian Zoroastrians were able to prosper and to build new temples and facilities for their community, including a small museum at Yazd. Introduction Pasargadae and Persepolis Sassanid Bishapur Achaemenid Tombs and Sassanid Reliefs Seljuk small towns (Ardestan, Zavareh and Abarquh) Seljuk Isfahan XIVth century Yazd Safavid Isfahan XVIIIth century Shiraz Qajar Kashan Post Scriptum On the Road An excursion to Abyaneh Persian Roses People of Iran     |