What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in June 2014. |

- Bishapur - Bishapur(dome of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque at Isfahan) You may wish to read an introduction to this section first.

Bishapur was founded by Shapur, second Sassanid king, to celebrate his victory over the Romans in 260 AD. He was the son of Ardashir (Artaxerxes in Greek), a governor of Persia who deposed the last Parthian king in 228 and proclaimed himself Shahenshah (king of kings). Ardashir was the son or the grandson of Sasan, perhaps a Zoroastrian grand priest, thus the dynasty he founded was called Sassanid. Ardashir claimed to be the heir of the Achaemenid (or First Persian) Empire which had ended in 330 BC with the seizure of Persepolis by Alexander the Great. The entire continent opposite Europe, separated from it by the Aegean Sea and the Propontic Gulf, and the region called Asia he (Artaxerxes) wished to recover for the Persian empire. Believing these regions to be his by inheritance, he declared that all the countries in that area, including Ionia and Caria (in south-western Turkey), had been ruled by Persian governors, beginning with Cyrus, who first made the Median empire Persian, and ending with Darius, the last of the Persian monarchs, whose kingdom was seized by Alexander the Great. He asserted that it was therefore proper for him to recover for the Persians the kingdom which they had formerly possessed. Herodian - History of the Roman Empire since the Death of Marcus Aurelius - Book VI - Translation by Edward C. Echols.

In 232 Emperor Alexander Severus led a major army against Ardashir, who in the previous years had raided several Roman territories. The campaign was poorly organised and the Roman legions had significant losses, yet Ardashir remained quiet and did not take up arms for four years after the campaign. (Herodian) In 235 Alexander Severus was killed by his own soldiers and for the Roman Empire a long period of anarchy began. The year 238 is known as the Year of the Six Emperors because six people were recognised as emperors. Ardashir decided to profit from the chaos reigning at Rome. He invaded Syria and probably he even conquered Antioch, at the time its most important city. He named Shapur to the throne one year before his death in 241.

In 243 a Roman army led by Emperor Gordian III (who was just 18) won back most of Syria and the key towns of Zeugma and Carrhae in today's Turkey. In an inscription at Naqsh-e Rostam Shapur claimed he killed Gordian III in a battle. According to Roman sources the death of the emperor was the result of a plot by Philip the Arab, commander of the Praetorian Guard, who became the new emperor. He immediately signed a humiliating peace treaty and he declared himself vassal of Shapur (more on him in a page covering his hometown). In 260 the Sassanids laid siege to Edessa (today's Sanliurfa) and Emperor Valerian led an army to help the defenders. According to Shapur's account Valerian was captured in battle, but according to Zosimus, a Byzantine historian desiring the emperor to come and speak with Shapur in person concerning the affairs he wished to adjust (..) he went without consideration to Shapur with a small retinue, to treat for a peace, was presently laid hold of by the enemy, and so ended his days in the capacity of a slave among the Persians, to the disgrace of the Roman name in all future times. Zosimus - New History - Book I.

Ctesiphon, near today's Baghdad, in central Mesopotamia, a very rich province, was the capital of the Parthians and after them of the Sassanids. It was however subject to being seized by the Romans and this had already occurred in 116 (Trajan), in 164 (Lucius Verus) and 198 (Septimius Severus). Shapur decided the city he was giving his name should not be at risk of being conquered by the enemy. He therefore chose a remote location in the tableland south-east of Mesopotamia which the Romans were very unlikely to be able to reach.

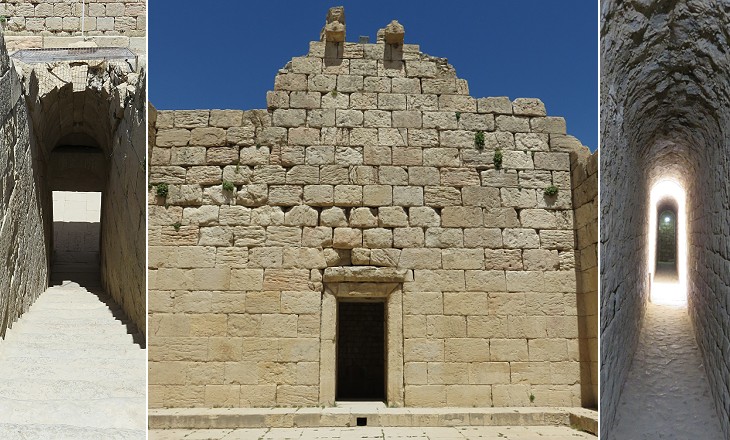

According to Sassanid sources Shapur made entire legions prisoner and Bishapur was built by Roman slaves. As a matter of fact some features of the palaces and temples so far excavated recall Roman monuments: the vault of the stairs of the temple resembles that of the internal passages of a Roman theatre. There is uncertainty about the dedication of the temple; the prevalent opinion says it was dedicated to Anahita, a fertility goddess.

The so-called Palace of Shapur, the main building found in the excavated area, has a number of niches which is typical of Roman monuments where they housed statues of gods or emperors. The design of the palace however is a forerunner of Islamic art because it has three large iwans, structures open on one side with usually very high walls. Iwans can be seen in the portals of mosques or medreses as at Samarkand or in palaces as at Khiva, but also in smaller buildings where they reduce the heat by favouring the movement of the air as at Bimaristan Argoun in Aleppo.

In 1939-41 Roman Ghirshman, a Russian-born French archaeologist, found at Bishapur some reliefs and mosaics which show the elaborate decoration of the palace which is hardly perceivable at the site.

Roman legionaries had knowledge of advanced construction techniques, but the finding of some high quality mosaics indicates that Shapur could rely on a number of skilled mosaicists in addition to the enslaved Roman soldiers. They most likely came from Antioch, where the making of mosaics had reached a peak. It is possible that these mosaicists moved to Bishapur as a result of clauses of peace treaties or just because they were offered good wages.

The choice of the site where Bishapur was built had advantages from a military viewpoint, but not from the economic one. Perhaps already a century after its foundation the town had already declined. Muslim chronicles have very few references to Bishapur. A Xth century traveller reported it in ruins.

The gorge of the River Chogan houses six large reliefs celebrating Shapur and other Sassanid kings. They are similar to some of those which were carved near the tombs of Achaemenid kings at Naqsh-e Rostam and Naqsh-e Rajab near Persepolis. Some iconographic details such as the cupid in the first relief shown in this page (similar to a mosaic at Bulla) and the array of horses (similar to those in the Monument to Aelius Gutta Calpurnianus) indicate the presence of Roman/Hellenized sculptors.

A western visitor to Bishapur is struck by the appearance of the Sassanid kings. They do not seem to belong to an ancient civilization, but to come out from a French XVth century illustrated book of prayers. The kings are very similar to those of the European nations of that period. The elaborate hairstyle, the flying cloak and the muslin trousers of Ahuramazda would have been admired by King Louis XIV of France and by Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Towards the end of the IIIrd century Roman coins started to portray the emperors wearing a crown of solid gold, rather than the usual laurel wreath. It was most likely due to the influence of the Sassanid way of depicting their kings and gods.

Large rock carvings were not unknown in ancient civilizations (you may wish to see a large Hittite relief at Ivriz in Turkey), but the Sassanids used them much more frequently. In the XIXth century the Qajar kings of Persia imitated the Sassanid ones and many carvings were made portraying them and their court. In 1830 a Sassanid king was wiped out from an ancient relief to make room for a Qajar king. Eventually the mountain with that carving was blown up to obtain material for construction.

The fact that this relief is unfinished and is the last shows that at the time of King Shapur II (309-79) the town had lost relevance. Shapur II had many accomplishments to celebrate, including the temporary occupation of Amida (today's Diyarbakir), a key Roman fortress on the River Tigris. He claimed to have killed Emperor Julian and to have imposed humiliating peace conditions on Jovian, Julian's successor.

The statue of Shapur, in full round and three times life-size is at the mouth of a cave three miles up the valley behind the gorge. A climb of 600 feet leads up to it. The last fifteen were perpendicular, and I stuck, while the valley swam below me. But before I could resist, the villagers had bundled me up like a sack, as they did our lunch and wine. At present a crowned head with a Velasquez beard and the curls of a Spanish Infanta lies at the bottom of the cavity, above which inclines a torso with sprigged with muslin tassels and broken off at the thighs. Robert Byron - The Road to Oxiana - Macmillan 1937 (piece written in February 1934). Introduction Pasargadae and Persepolis Achaemenid Tombs and Sassanid Reliefs near Persepolis Zoroastrian survivors Seljuk small towns (Ardestan, Zavareh and Abarquh) Seljuk Isfahan XIVth century Yazd Safavid Isfahan XVIIIth century Shiraz Qajar Kashan Post Scriptum On the Road An excursion to Abyaneh Persian Roses People of Iran     |