What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in June 2014. |

- Safavid Isfahan - Naqsh-e Jahan - Safavid Isfahan - Naqsh-e Jahan(dome of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque at Isfahan) You may wish to read an introduction to this section first.

In 1588 Shah Abbas, then sixteen, became the ruler of the Safavid Empire which had been founded at the beginning of the century. He had to face a double threat: the Ottoman Empire to the west and the Khanate of Bukhara to the east. During the XVIth century the Ottomans had seized Tabriz, the Safavid capital until 1555, four times. Qazvin, the new capital, was not far enough from the border, thus Shah Abbas decided to relocate his court to Isfahan in the centre of the Persian tableland. The decision to move the capital to a more secure location was perhaps suggested by what Sassanid king Shapur had done when he founded Bishapur in 260 AD.

The Ottoman army had a technological edge over the Safavid one, because of their wide use of firearms and artillery. In 1590 Shah Abbas signed a peace treaty with the Ottomans on very unfavourable terms, with the aim of gaining time to reorganize his army. He achieved this objective in the following years and in 1598 he managed to defeat the Khan of Bukhara and he won back Khorasan (Land of Sunrise), the eastern provinces of today's Iran (you may wish to see a 1900 map of Persia and Central Asia - the three dots indicate Khiva, Bukhara and Samarkand - it opens in another window). In 1603 Shah Abbas declared war on the Ottomans and after a number of successful campaigns forced Ottoman Sultan Ahmet I to acknowledge the loss of Baghdad, Tabriz and vast territories in the Caucasus (Treaty of Serav 1618). Shah Abbas decided to make Isfahan the symbol of Persian power by moving the city centre to the south of the old one to reach Zayandeh Rud, the only stream of the arid tableland which deserves the name of river. The gigantic size of Naqsh-e Jahan, the meydan (large square) of the new city, helped to bridge the distance between the old town and the river. Its space was used for polo games, a sport which is believed to have been first played by the Sassanids.

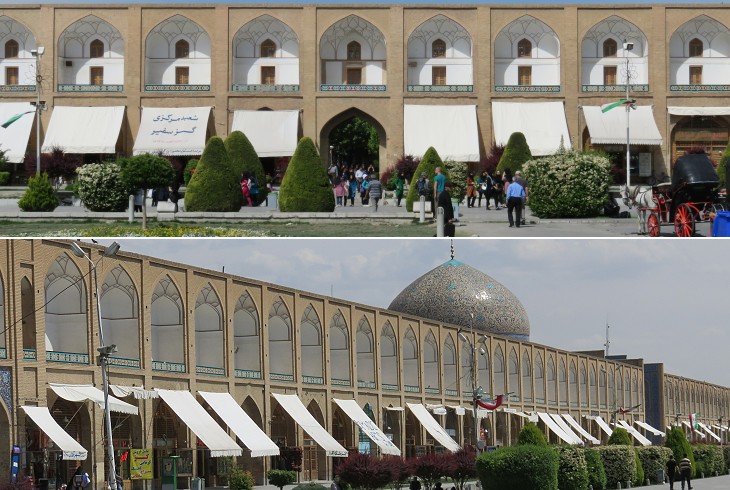

Travel books abound in comparisons between the size of Naqsh-e Jahan and that of other world known squares and apparently only the modern square in front of the Gate of Heavenly Peace in Beijing is larger. Size apart, the most interesting comparison is with Place des Vosges in Paris (it opens in another window) which was designed almost at the same time as Naqsh-e Jahan, but perhaps slightly later and has a similar uniform design. The size of Naqsh-e Jahan however makes the four monuments which embellish it appear too small. Engravings by European travellers increased the size of the monuments (or reduced that of the square) to make their views of Naqsh-e Jahan more impressive (you may wish to see an 1840 view by French Eugène Flandin - it opens in another window).

Qaysariya is another transliteration of the bazaar's name which more clearly indicates its origin from Julius Caesar and its meaning. The decision to build a major addition to the existing bazaar shows the attention Shah Abbas paid to the economic development of Isfahan and in general of the whole country. In order to develop the economy of his new capital he deported thousands of Armenian skilled workers and merchants from Julfa* to Isfahan, where they settled in a separate quarter south of the river. Trade with Europe had to go through the Ottoman Empire territories and therefore Shah Abbas favoured the opening of new routes through Russia which in 1557 had seized Astrakhan on the Caspian Sea and was therefore directly bordering on Persia. Shah Abbas ousted the Portuguese from some of their bases in the Persian Gulf to break their monopoly on sea trade and he established maritime routes with Britain. * Julfa was a town located on the River Aras which today separates Iran from Azerbaijan.

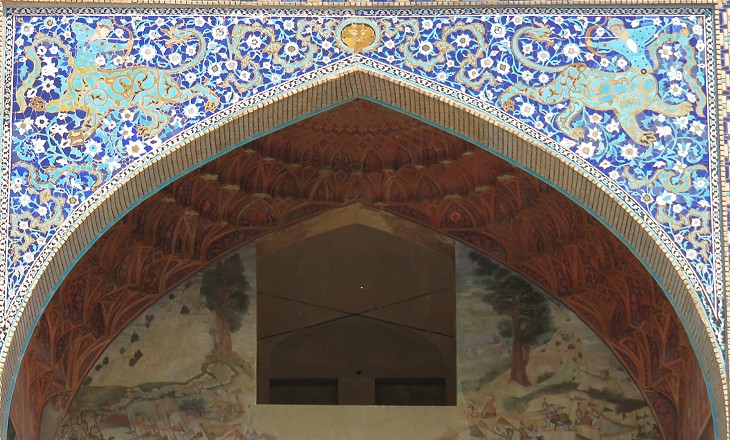

The Muslim ban on depiction of living beings was fully respected in the decoration of the mosques of Naqsh-e Jahan, but entirely disregarded in the portal of the bazaar which recalls the portal of Chin Dor Medrese at Samarkand. Sagittarius was regarded as patron of trade, similar to Hermes for the Greeks. The zodiacal sign was painted in turquoise because this stone/colour is believed to bring good luck (in Persia and in most Muslim countries).

In 1614 Pietro della Valle, a young Roman man whose ancestors included Cardinal Andrea della Valle, undertook a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and afterwards he travelled extensively through Syria, Persia and India until he returned home in 1626. In 1616 he decided to visit Isfahan with Ma'ani his young wife, a Christian girl from Mardin. I set about changing my clothes from Syrian to Persian and I found a barber who shaved off the beard I had cultivated during the previous sixteen months. I wanted him to make me look completely Persian, in other words with cheek and chin shaved and with long moustaches. Ma'ani was heartbroken when she saw me, but I explained her that when travelling to different countries, it is necessary to adapt to different customs. From Caroline Stone's "Pietro della Valle - Pilgrim of Curiosity" - Saudi Aramco World - Jan/Feb 2014 Issue.

Sir John Chardin, a Franco-British jeweller and traveller visited Isfahan in 1673. The city of Isfahan including the suburbs is one of the largest in the world and is not less than 12 leagues or 24 miles in circuit. The Persians say to exalt its greatness that Isfahan is half the world. Many persons carry the number of the inhabitants to 1,100,000 souls. Those who place it the lowest affirm that it amounts to 600,000. Journal du voiage du Chevalier Chardin en Perse et aux Indes orientales la Mer Noire et par la Colchide. Qui contient le voiage de Paris à Ispahan - Amsterdam - 1686. The assessment of the population made by Chardin helps in understanding why Isfahan had such a large bazaar which surrounded Naqsh-e Jahan on all sides and from there stretched to the old city centre for more than a mile.

The portal gives access to the major artery of the bazaar. Mosques, hammams and khans are located off this main street, much of which is lit by circular openings cut into the brick vaults, creating shafts of light dotting the passage at certain times of the day. The bazaar splits into various smaller bazaars towards the older section to the north, where each alley is dedicated to a specific trade. European cities which have retained their historical place-names have a "Market Square" surrounded by small streets named after the trades taking place there. This is almost all that was done by local rulers to promote trade, whereas Muslim rulers did much more. Sultan Mehmet II started to build the Great Bazaar of Constantinople in 1461 only eight years after having conquered the city. In general some of the most impressive Islamic monuments are related to trade infrastructures from caravanserais (e.g. Sultanhan) to khans (e.g. Qourtbak Khan in Aleppo) to bazaars.

The Last Supper on sale at the bazaar is most likely a Chinese bric-a-brac, but perhaps it has to do with a long tradition. In the evening Shah Abbas wandered about the town visiting coffeehouses and shops, including that of an Italian art dealer who sold, among other things, portraits of the kind they sell for a crown (or rather a "paolo", a silver coin minted in Rome) at Piazza Navona..., but which here cost ten sequins (a gold coin minted by the Republic of Venice) and are considered cheap at the price. From Caroline Stone's "Pietro della Valle - Pilgrim of Curiosity" - Saudi Aramco World - Jan/Feb 2014 Issue.

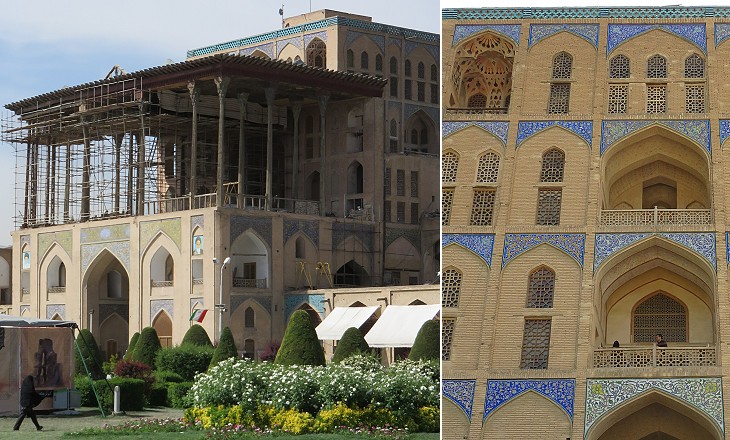

The construction of a series of palaces for Shah Abbas and his court began in 1592, in preparation of the capital move. Kapi in Turkish means gate (see a page on the gates of Constantinople) and Ali Qapu was the gate of a royal compound which included larger palaces. The building was enlarged by the successors of Shah Abbas with the addition of several storeys and a covered terrace.

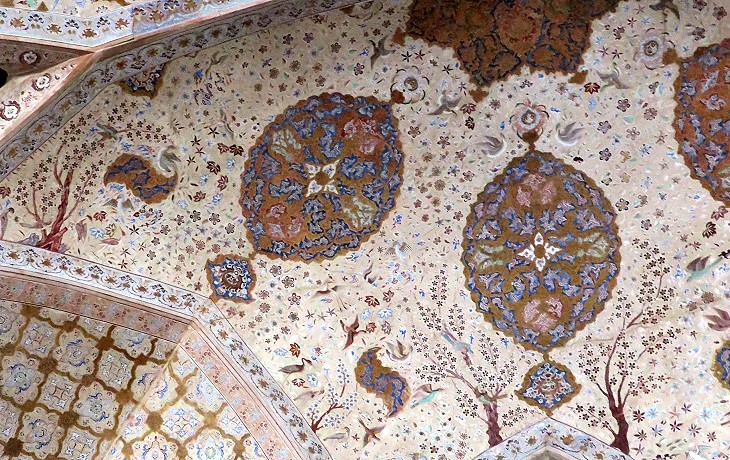

The decoration of Ali Qapu is attributed to Reza Abbasi who is best known for his book miniatures portraying young men and women. In these miniatures Reza Abbasi was careful not to overdo the decoration of the background (you may wish to see one of his miniatures - it opens in another window) and he applied the same approach at Ali Qapu.

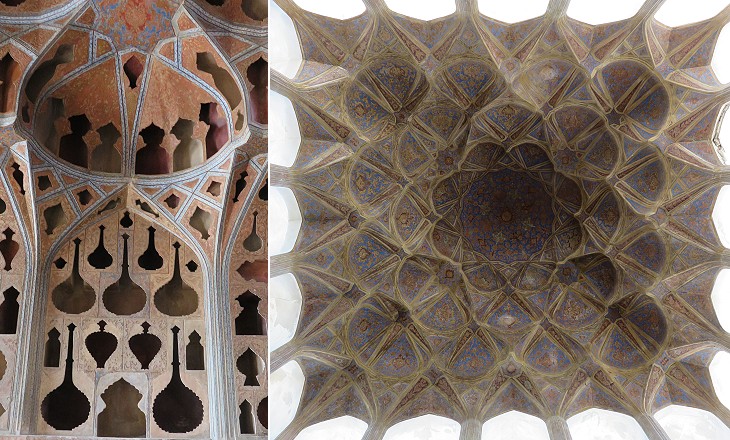

The guests of the Safavid Shahs must have been in top physical form to climb the 94 steep and spiralling steps leading to the music chamber on the top floor. The effort however was rewarded by the excellent acoustics of the hall, thanks to a series of hollow panels. The holes have the shape of kamancheh, a typical Persian bowed string instrument. Chehel Sotun, the main palace of Shah Abbas, was decorated with paintings showing musicians and dancers.

The image used as background for this page shows a lamp at the bazaar. Other Isfahan pages: Seljuk Isfahan Shah Abbas Mosque Other Mosques Royal Palaces Southern Quarters Introduction Achaemenid Pasargadae and Persepolis Sassanid Bishapur Achaemenid Tombs and Sassanid Reliefs near Persepolis Zoroastrian survivors Seljuk small towns (Ardestan, Zavareh and Abarquh) XIVth century Yazd XVIIIth century Shiraz Qajar Kashan Post Scriptum On the Road An excursion to Abyaneh Persian Roses People of Iran     |