What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in November 2013. |

- Introduction - Introduction

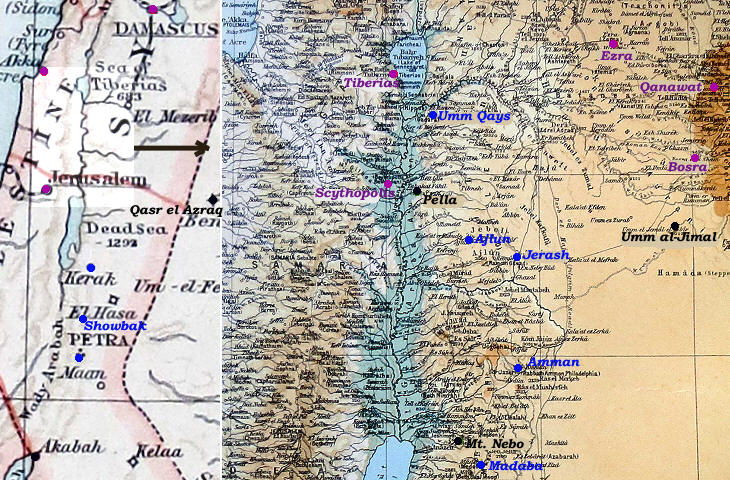

(left: J. L. Burckhardt in Arab attire in a XIXth century engraving; right: the Treasury of Petra) Johann Ludwig Burckhardt (1784-1819) was a Swiss explorer who wanted to discover the source of the River Niger. He believed he could reach his aim by becoming fluent in Arabic and having an in-depth knowledge of the Muslim way of living. In 1809 he moved to Aleppo in Syria where he studied the Qur'an, probably converted to Islam and took the name of Ibrahim. In April-May 1812 he visited the region to the east of the Lake of Tiberias and in the summer of that same year he decided to reach Cairo by following an itinerary to the east of the River Jordan valley and the Dead Sea, rather than through the usual route across the Holy Land. At Cairo Burckhardt hoped to join a caravan going south-west across the Fezzan region towards the assumed location of the River Niger source.

Burckhardt ventured across a region which was nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, but actually was a lawless land, exception made for some small towns. Burckhardt had to conceal his interest for ancient monuments as the locals regarded it as an attempt to steal by magic the treasures they were supposed to house. Most of the territories he crossed were inhabited by Bedouin tribes who were hostile one to another and he was often at a standstill because no one was willing to guide him to an area controlled by another tribe. Notwithstanding all these difficulties he managed to visit several ancient sites and eventually Petra, the capital of a kingdom which was annexed to the Roman Empire by Emperor Trajan in 106 AD. Burckhardt sent accounts of his travels to the British African Society, which promoted the exploration of that continent. They were published in 1822, after Burckhardt's death in Cairo in 1817, which was caused by dysentery.

Burckhardt very rarely slept under a roof in his journey. He had to adapt to the primitive living conditions of the Bedouins. In the valley of Wale (south of Madaba) a large party of Arabs Sherarat was encamped, Bedouins of the Arabian desert, who resort hither in summer for pasturage. They are a tribe of upwards of five thousand tents; but not having been able to possess themselves of a district fertile in pasturage, (..) they wander about in misery, have very few horses, and are not able to feed any flocks of sheep or goats. (..) They are obliged to content themselves with encamping on spots where the Beni Szakher and the Aeneze, with whom they always endeavour to live at peace, do not choose to pasture their cattle. The only wealth of the Sherarat consists in camels. Their tents are very miserable; both men and women go almost naked, the former being only covered round the waist, and the women wearing nothing but a loose shirt hanging in rags about them. These Arabs are much leaner than the Aeneze, and of a browner complexion. They have the reputation of being very sly and enterprising thieves, a title by which they think themselves greatly honoured. J. L. Burckhardt - Travels in Syria and the Holy Land - 1822

Jordan has some Biblical memories. Burckhardt roughly made the reverse journey of Moses from near Mt. Nebo, where the prophet died in sight of the Promised Land, to Egypt. He managed to reach Wady Mousa, the faraway location where he discovered Petra, by claiming he wanted to go there to sacrifice a goat at the tomb of Aaron, Moses' brother. The tomb, on the summit of a mountain, was regarded as a holy site by Muslims.

In 1818 Charles Leonard Irby and James Mangle, commanders in the British Royal Navy, visited Petra and described it in more details in a book published in 1823. The public at large "discovered" Petra through some engravings published in 1842-49 based on drawings by David Roberts, a Scottish painter, who visited the region in 1839. XIXth century historians and art historians were puzzled by the gigantic fašades of tombs cut into the rocks surrounding the town. Ancient Roman sources provided limited knowledge about the Nabatean kingdom of which Petra was the capital. Today we know that it almost surrounded the Kingdom of Herod the Great in the Ist century BC. Ruins of major Nabatean towns can be found in three countries: Israel (Oboda and Mamfis in the Negev Desert), Jordan (Petra) and Syria (Bosra).

I had, at most, only four hours to make my survey, and it was with great difficulty that I could persuade my three companions to wait so long for me. None of them would accompany me through the ruins, on account of their fear of the Bedouins, who are in the habit of visiting this Wady. They therefore concealed themselves beneath the trees that overshadow the river. (..) I did not examine the ruins closely; meaning to return to them in taking a review of what I had already seen, but my guides were so tired with waiting, that they positively refused to expose their persons longer to danger, and walked off, leaving me the alternative of remaining alone in this desolate spot, or of abandoning the hope of correcting my notes by a second examination of the ruins. J. L. Burckhardt In May 1812 Burckhardt visited Jerash, one of the main Roman towns of the region. Notwithstanding the limited time he had, his description of the ruins is pretty accurate. The Romans promoted farming to strengthen their control of the region and Jerash (ancient Gerasa) became a wealthy town with paved colonnaded streets, baths, fountains, two theatres and a hippodrome.

Today the town of Madaba, near Mt. Nebo, attracts visitors owing to a mosaic depicting a map of the Holy Land which includes a detailed representation of the City of Jerusalem (it opens in a separate window). When Burckhardt visited Madaba, this and other mosaics had not been uncovered yet. The tableland to the east of the River Jordan Valley and the Dead Sea continued to be intensively farmed until the mid of the VIth century. A pestilence, high taxation and the Sassanid (Persian) invasion of the region in 614 caused a general impoverishment.

The Byzantine reconquest of the region was short-lived; in 629 at Mutah, south of Kerak, the first Muslim army made its appearance. It was not a major battle, but many Byzantine mercenaries defected and the Muslims understood their enemy was financially exhausted and unable to recruit new troops. In 636 at the River Yarmouk, near the Lake of Tiberias, the Muslims won a decisive battle which gave them control over Syria and the Holy Land. The Umayyad Caliphate (661-750) had its capital at Damascus and pursued a policy of tolerance towards the non-Muslims. The Caliphs of this dynasty promoted the construction of mosques and palaces, the design of which was still influenced by the canons of classic art.

The Umayyads were replaced by the Abassids, who were based in Baghdad, and today's Jordan fell into a state of abandonment. Farming was discontinued in most parts of the country. A few castles built by the Crusaders or by their opponents (Ayubbids, Mamelukes) are the only monuments of a period of more than a thousand years. The Crusaders called their territories east of the River Jordan Outrejourdain (Transjordan). The Ottomans conquered the region in the early XVIth century, but they did not care about this province of their empire. Even the yearly pilgrimage from Damascus to Mecca avoided the tableland and followed a route through the desert. In 1900 the Ottoman government, backed by German advice and support, started the construction of a railway from Damascus to Mecca which crossed the tableland and favoured the development of small towns. The railway reached Medina, 250 miles north of Mecca, in 1908. At the end of 1918 the Ottoman territories in the Middle East were partitioned between the United Kingdom and France. In 1922 the British Mandate over Transjordan was recognized by the League of Nations. The estimated population of the country was 225,000. In 1946 the independence of Transjordan was approved by the United Nations. The name of the state was changed into Jordan after the (temporary) annexation of Jerusalem and the Palestinian West Bank in 1948. The image used as background for this page shows a typical decoration of tombs at Petra. Move to: Ajlun Castle and Pella (May 3rd, 1812) Amman and its environs (July 7th, 1812) Aqaba "Castles" in the Desert (incl. Qasr el-Azraq) Jerash (May 2nd, 1812) Madaba (July 13th, 1812) Mt. Nebo and the Dead Sea (July 14th, 1812) On the Road to Petra (incl. Kerak and Showbak) (July 14th - August 19th, 1812) Petra (August 22nd, 1812) Umm al-Jimal Umm Qays (May 5th, 1812)

|