What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in June 2013. |

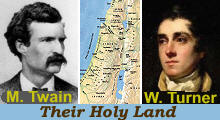

- Introduction - Introduction(relief at Scythopolis) You may wish to visit this section after having toured the Holy Land with William Turner and Mark Twain in a section which covers some ancient towns i.e. Caesarea Philippi, Jerusalem and Tiberias.

The monuments of the ancient towns covered in this section, exception made for Megiddo and for the acropolis of Scythopolis, were built in the period beginning with the Kingdom of Herod the Great (37-4 BC) and ending with the conquest of Jerusalem by Sassanid (Persian) Emperor Khosrau II (614 AD).

With the exceptions mentioned before the works of art of the ancient towns of this section all fall into the broad category of Hellenistic/Roman art, which developed after Alexander the Great created a vast empire which spread from Macedonia, his homeland, to western India. In 332 BC he entered today's Israel at Rosh Haniqra. At his death the country was included in the Empire of Seleucus, one of his generals. In the IInd century BC, at a time when the Seleucid Empire was weakened by a long confrontation with Rome, a revolt broke out in Jerusalem which led to the creation of an independent kingdom in Judea. Dynastic quarrels brought about the involvement of Rome in the country and in 63 BC Pompey intervened in one of these conflicts and seized Jerusalem. Eventually the appointments of the Kings of Judea were decided by the Roman Senate.

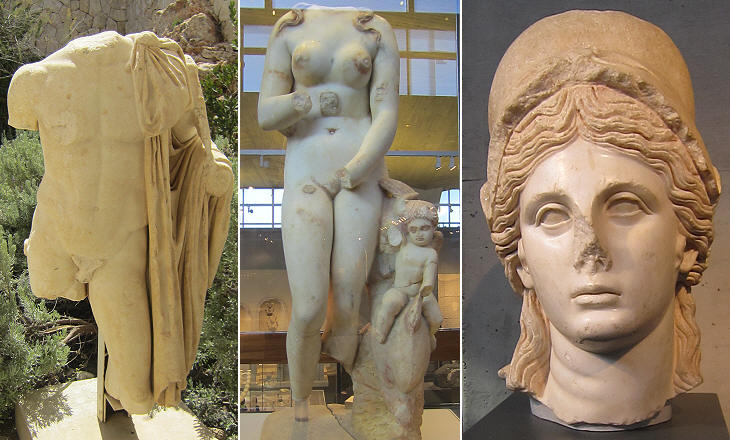

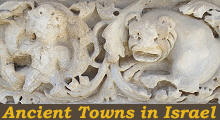

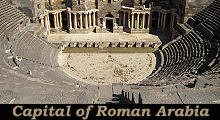

In no other place in the ancient world a statue of a goddess or of an emperor has had less chance to survive to the present day than in Israel. The Jewish and Christian populations of the country regarded them as execrable idols, the Sassanids hated them as symbols of the enemy's civilization and the Arabs did the same for both religious and national reasons. And yet there were so many statues in the ancient towns that the Museum of Israel has a pretty extensive collection of them. In general they were made abroad, maybe at Afrodisias, a town in today's Turkey which provided sculptures to the whole Roman Empire.

The expansion in the Levant of the Romans was welcomed by some independent towns and small kingdoms which in return were not annexed to the Roman Empire. The Nabatean kingdom almost surrounded that of Judea; it included the Negev desert in southern Israel, western Jordan and a small part of southern Syria. The capital was Petra in Jordan and then Bosra in southern Syria until 106 AD when Emperor Trajan annexed the Nabatean kingdom to the Roman Empire. The Kingdom of Judea was partitioned by King Herod the Great among his three sons and his sister. These very small kingdoms were annexed one by one by the Romans, although in some cases the heirs of Herod (e.g. Agrippa II at Caesarea Philippi) retained their actual power as representatives of the emperor. Direct Roman rule caused a greater Hellenization of the country and eventually a reaction by the more religious-minded sections of the Jewish population. The First Jewish Revolt (66-73 AD) ended with the destruction of Jerusalem and of the Second Temple by Titus, Emperor Vespasian's son. The Second Jewish Revolt (132-36) was quelled by Emperor Hadrian who forbid the Jews from returning to Jerusalem, which he had rebuilt with the name of Aelia Capitolina. A consequence of this second revolt was that the Roman province of Judea was merged with Syria to form Syria Palaestina which had its capital at Antioch.

In order to maintain a firm grip on the country Hadrian stationed permanently a legion near Megiddo. At the same time as part of his policy of consolidation, rather than expansion of the Empire, he committed the legion a general improvement of key facilities such as roads and aqueducts. Emperors Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius lifted some of the sanctions Hadrian had imposed on the Jews and during their rule the country enjoyed a period of peace and economic development.

Not all the Jewish communities joined the rebels in particular during the Second Revolt. Hadrian prevented the Jews from returning to Jerusalem, but he did not expel them from the country. Galilee became the seat of rabbinic learning and of a Patriarchate which was recognized by Rome as having the ultimate authority on many matters concerning Jewish communities. The Patriarchate was located in some of the towns covered in this section such as Diocaesarea (aka Sepphoris) and Scythopolis.

Archaeologists have found evidence of the spreading in the country of cults which became very popular in many parts of the Empire, including Rome, in the IInd/IIIrd century AD (you may wish to see similar exhibits at Villa dei Quintili). Caesarea Marittima was the main port and town of the country and it had a cosmopolitan population. Scythopolis was part of Decapolis, a loose federation of ten towns in today's Syria, Jordan and Israel which included Damascus and Canatha (Qanawat) and it had a mixed population.

While most of the paintings which decorated the ancient buildings have been lost when the walls collapsed or because of humidity, in many cases the mosaics which decorated the floors have survived to the present time in excellent condition. Those found in Israel were probably made by mosaicists who came either from Egypt or from Syria. Egyptian mosaicists loved to depict large scenes with many characters and river landscapes in the background (you may wish to see the Nile Mosaic at Palestrina). Mosaicists from Syria made a larger use of decorative themes and frames, including "living scrolls", as in the mosaic shown above (you may wish to see a similar mosaic at Philippopolis in Syria). The mosaics found at synagogues are of particular interest because they show scenes from the Bible such as the sacrifice of Isaac or other personages, thus indicating that the prohibition of depicting living creatures was disregarded.

Contrary to expectations, there are not many early churches in Israel and the most interesting ones are in the former Nabatean towns of Mamfis and Oboda. Many churches were destroyed by the Sassanids and by the Arabs in the VIIth century. The Crusaders pulled down some ancient churches to replace them with new buildings which in turn were destroyed by the Mamelukes. In the XIXth-XXth centuries renovations and enlargements did not care to preserve the ancient buildings, including the Holy Sepulchre. The image used as background for this page shows a detail of a mosaic at Caesarea. Move to: Ancient Synagogues: Introduction, Korazim, Capernaum and Hamat Teverya Ancient Synagogues: Bet Alpha, Diocaesarea and Ein Gedi Caesarea Diocaesarea (Zippori) Herodion Mamfis (Mamshit) Masada Megiddo Necropolis of Bet She'arim Oboda (Avdat) Scythopolis (Bet She'an)     |