What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page revised in August 2015. |

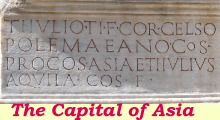

- Ephesus - Ephesus(inscription in the Library built by Consul Julius Aquila to celebrate his father Julius Celsus Polemenus, proconsul of Asia) Often as I have visited the ruins of Ephesus, the place has such a witchery for me, that I am always ready to go there, and as reluctant to leave it. Francis Vyvyan Jago Arundell - Discoveries in Asia Minor - 1834 The Artemision Artemis (Diana) is generally known as the Maiden of the Silver Bow, her bow being a symbol of the new moon. Yet Artemis was also depicted as an orgiastic Nymph, a fertility goddess. According to the Greek myth the Amazons dedicated a temple to Artemis near Ephesus, a town on the eastern shore of the Aegean Sea. Statues of the Ephesian goddess can be seen in the Archaeological Museum of the town.

Archaeologists have found evidence of a temple dating back to the VIIth century BC, but the Artemision which was listed among the Seven Wonders of the World was most likely built around 550 BC by Croesus, the rich King of Lydia. In 356 BC a man set fire to the temple in an attempt to immortalize his name. The temple was restored and it remained a renowned sanctuary in the following centuries when the region became part of the Roman Empire. In 263 AD the Goths sacked the Artemision, which was once more restored; it continued to attract worshippers and in 401 this led St. John Chrysostom (Golden Mouth - a reference to his eloquence) to request Emperor Arcadius (395-408) to close it. Its stones and decorative elements were used as building material for Byzantine and Islamic monuments, including Hagia Sophia at Constantinople.

The first western travellers who visited Ephesus saw no evidence whatsoever of the Artemision and some of them figured out it was situated next to the harbour of the town because they mistook a large Roman basilica for the Temple to Artemis. Eventually John Turtle Wood, a British architect, engineer and archaeologist, discovered the site of the Artemision in January 1870: Xenophon says: "At Ephesus, the river Selinus runs past the Temple of Artemis, and there are fish and shells in it." This testimony is confirmed by Strabo in almost the same words. Xenophon speaks of the old Temple, Strabo of the new, and both were eye-witnesses. (..) Pliny says: "They built the Temple in a marshy soil, in order that it should not suffer from the earthquakes, nor be exposed to cracks." The site of the Temple must therefore be sought for in the low ground. (..) Many inscriptions were found on the stage of the Great Theatre; but there was a much greater prize awaiting my discovery. I had examined the marbles on the stage by turning them over from north to south. When I came to clear the southern entrance I found the whole of the eastern wall of that entrance inscribed with a series of decrees, chiefly relating to a number of gold and silver images, weighing from three to seven pounds each, which were voted to Artemis, and ordered to be placed in her Temple, by a certain wealthy Roman, named C. Vibius Salutarius. (..) On a certain day of assembly in the Theatre, viz., May 25, which was the birthday of the goddess, these images were to be carried in procession from the Temple to the Theatre by the priests, accompanied by a staff-bearer and guards, and to be met at the Magnesian gate by the Ephebi or young men of the city, who, from that point, took part in the procession, and helped to carry the images to the Theatre. (..) In one of the decrees contained in this inscription, the consuls of the year A.D. 104 are mentioned. In another, the Emperor Trajan is mentioned as then reigning. (..) Before the close of the year I had succeeded in finding the Magnesian gate (..). I had to clear a wide space, for the distance of 140 feet outside the gate, before I reached the point where the road bifurcated, one branch of it leading around Mount Coressus towards Ayasalouk, the other towards the Ephesus Pass, and onward to Magnesia ad Maeandrum. I soon determined which of these two roads was more likely to lead to the Temple. The road leading to Ayasalouk, thirty-five feet in width, and paved with immense blocks of marble and limestone, was very deeply worn into four distinct ruts, showing the constant passing and repassing of chariots and other vehicles. (..) Where the road changes direction at rather an acute angle, to make its course conformable to the shape of the mountain, I found a continuous row of sarcophagi succeeded for some distance by tombs of every description. (..) In this Street of Tombs, which, as I eventually learnt. led to the Temple, and which I would venture to call the Via Sacra, were found hundreds of terra-cotta lamps of various forms and sizes (..) I here found the road I had been so anxiously looking for, leading away from the foot of the mountain towards the cemetery at Ayasalouk (..). This discovery was another great stride towards success. As far as I was able to explore it on both sides of the road were marble sarcophagi (..). I now carefully studied the ground in the immediate neighbourhood of the morsel of wall found near some olive trees. I observed that the wall took the same direction as that of a modern boundary which formed an angle near the trench I had dug. Suspecting that the modern boundary might mark the position of an ancient wall, I cut another large trench and hit most fortunately upon the angle of the wall into which were built two large stones, equidistant from the angle, with duplicate inscriptions in Latin and Greek, by which we are informed that this wall was built by order of Augustus in the twelfth year of his Consulate (..) and that it was to be paid for and maintained out of the revenues of the Artemisium and the Augusteum. This was therefore, without doubt, the wall of the Temenos (sacred area) of the Temple of Artemis, described by Tacitus as having been built by Augustus. John Turtle Wood - Discoveries at Ephesus, including the site and remains of the Great Temple of Diana - 1877

Ephesus

No list of Turkeys archaeological treasures could begin anywhere other than at Ephesus, the sprawling site just east of Selçuk that was at one time the capital of the Roman province of Asia Minor, with a population of around 250,000 people. (..) If Ephesus has one problem its that its a bit too popular for its own good (from the February 7, 2010 online edition of "Today's Zaman", a popular Turkish newspaper). A large tree-lined road which starts in the modern town of Selçuk and passes near the Artemision leads to Ephesus (and to the airport). Travellers who are not in a hurry enjoy walking to the ancient town along this road, but how more evocative would it be for them to be able to follow that discovered by Wood. Unfortunately the Ephesus Archaeological Site is more and more a well-oiled machine aimed at increasing the number of visitors. An "Ephesus à la carte" option is not available, but only a standardized itinerary which suits the needs of tour operators and reduces the cost of properly maintaining and guarding the whole archaeological area.

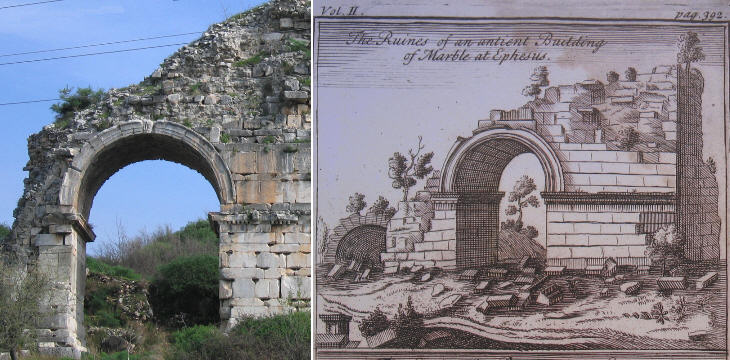

The first ancient monument visitors see when they approach (on foot) the archaeological site of Ephesus is the arch which was the main entrance to a stadium built during the reign of Emperor Nero. It is almost in the same condition as it was in the early XIXth century.

My next move was a three hours' ride to Ephesus, a place so familiar to the mind that one cannot but feel disappointed at not seeing realised all the ideas associated with it. The vicinity of Ephesus to the coast, as well as to Smyrna, has enabled many travellers to visit this celebrated city, and the memory of the past may perhaps have led them to indulge too freely their imagination whilst contemplating the few silent walls which remain. (..) A splendid circus or stadium remains tolerably entire. Charles Fellows - Journal Written during an Excursion in Asia Minor in 1838 Ephesus is one of the archaeological sites where the reconstruction of ancient monuments has been most practiced. It thus happens that visitors are not allowed to visit the remains of a building which was not excessively damaged by the ravages of time, because the focus of the almost compulsory itinerary is placed on reconstructed monuments.

(..) one of those gigantic and nameless piles of buildings seen alike at Pergamus and Troy (remains tolerably entire); by some they are called gymnasia, by others temples, and again, with I think more reason, palaces. They all came with the Roman conquest. C. Fellows

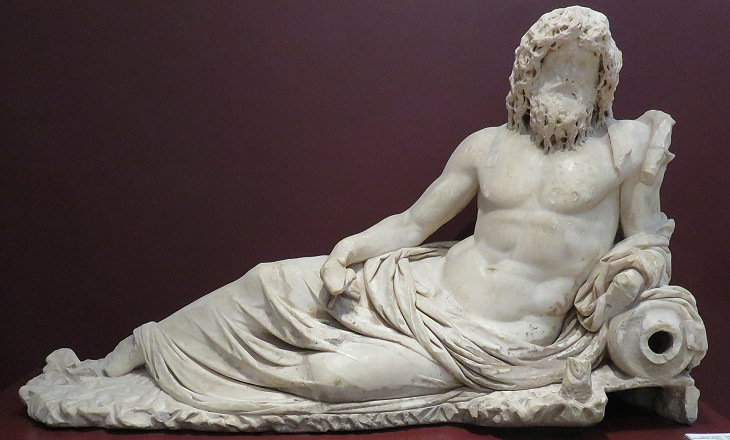

Some of the first archaeological excavations of Ephesus were carried out at the Gymnasium of Vedius which stands near the Stadium. Their yield was exceptional because the building was decorated with fine IInd century AD statues.

In 133 BC Attalus III of Pergamum bequeathed his kingdom which included Ephesus, to the Romans. The town flourished during Roman rule to the point that it replaced Pergamum as the residence of the proconsul in charge of Asia, the first Roman province on the soil of that continent.

What would have been the astonishment and grief of the beloved Apostle (St. John) and Timothy if they could have foreseen that a time would come when there would be in Ephesus neither angel, nor church, nor city! when the great city would become "heaps, a desolation, a dry land, and a wilderness, a land wherein no man dwelleth, neither doth any son of man pass thereby!" (Jeremiah 51:43). Once it had an idolatrous temple celebrated for its magnificence as one of the wonders of the world, and the mountains of Corissus and Prion re-echoed the shouts of ten thousand tongues, "Great is Diana of the Ephesians!" Once it had Christian temples almost rivalling the pagan in splendour, wherein the image that fell from Jupiter lay prostrate before the cross, and as many tongues moved by the Holy Ghost made public avowal that "Great is the Lord Jesus!" Once it had a bishop, the angel of the church, Timothy, the beloved disciple of St. John; and tradition reports that it was honoured with the last days of both these great men, and of the mother of our Lord. (..) A few unintelligible heaps of stones, with some mud cottages untenanted, are all the remains of the great city of the Ephesians! The busy hum of a mighty population is silent in death! "Thy riches and thy fairs, thy merchandize, thy mariners, and thy pilots, thy caulkers, and the occupiers of thy merchandize, and all thy men of war, are fallen." (Ezekiel 27:27) Even the sea has retired from the scene of desolation, and a pestilential morass, covered with mud and rushes, has succeeded to the waters which brought up the ships laden with merchandize from every country. Francis Vyvyan Jago Arundell - A Visit to the Seven Churches of Asia - 1828

Ruin of large Roman baths are situated near the harbour in what was the commercial centre of Ephesus. The harbour of Ephesus is now dry and the coastline is miles away from the town. This is due to the silting caused by the action of the river Küçük Menderes which carries a lot of sediments from the Anatolian plateau. menderes is the Turkish word for Latin meander, the winding course of a river through its own deposits.

A number of sarcophagi found along the roads departing from Ephesus have been gathered in an open space near Via Arcadiana, the street leading to the harbour. Many of them have a rather simple decoration based on festoons which was typical of the sarcophagi made at Ephesus (you may wish to see a much more elaborate sarcophagus from Ephesus in a page dealing with Roman funerary practices).

No inscription or ornament is to be found (at Ephesus), cities having been built out of this quarry of worked marble. C. Fellows In 1845 Charles Fellows was knighted for having shipped to England an enormous amount of reliefs and inscriptions from Xanthos, but he grossly underestimated the potential rewards which Ephesus could have provided to him (and the British Museum).

Of the site of the theatre (..) there can be no doubt, its ruins being a wreck of immense grandeur. I think it must have been larger than the one at Miletus, and that exceeds any I have elsewhere seen in scale, although not in ornament. Its form alone can now be spoken of, for every seat is removed, and the proscenium is a hill of ruins. C. Fellows We all stood in the vast theatre of ancient Ephesus, - the stone-benched amphitheatre I mean - and had our picture taken. We looked as proper there as we would look any where, I suppose. We do not embellish the general desolation of a desert much. We add what dignity we can to a stately ruin with our green umbrellas and jackasses, but it is little. However, we mean well. Mark Twain - The Pilgrims Abroad - 1869 The theatre of Ephesus could accommodate an audience of 25,000 and it was located with a very scenographic effect at the end of the colonnaded street which linked the harbour with the city centre.

The Magnesian Gate mentioned by Wood is situated in the Upper Town. It was linked to the harbour by a colonnaded street which was not straight because of the slope of the ground. Archaeologists have given the following names to its four sections: 1) Via Arcadiana from the harbour to the theatre; 2) Marble Street (because of its pavement) from the theatre to the Library of Celsus; 3) Street of the Kouretes (young participants to processions) from the Library to the Monument of Memmius in the Upper Town; 4) Procession Street from this monument to the Magnesian Gate. In a visit made in 2006 the archaeological site could be accessed only through the Lower Town, whereas in 2015, the large majority of visitors left their coaches at the Magnesian Gate and came down to the Lower Town through the colonnaded street (occasionally it was very awkward to move in the opposite direction). At Marble Street they were shown carvings which (I believe without much evidence) are assumed to be an advertisement of a purported nearby brothel. At the end of Marble Street a bilingual inscription catches the eye of (some) visitors, because at first sight it seems written in Greek and Aramaic (or Palmyrene). The second language is instead Latin, a very unusual kind of Latin handwriting. It is dated 585 AD and it contains instructions in Greek of Byzantine Emperor Maurice to the governor of Ephesus. The Latin words are limited to the dating: Dat(um) III Idus Februar(ias) Constantinupo(li), imp(er)a(toris) d(omini) n(ost)ri [Mauricii T] iberi pe(r)pe(tui) Aug(usti) ann(o) III et post cons(ulatum) eius(dem). The use of Latin in the Byzantine Empire was discontinued in 620.

Marble Street leads to the building which is the symbol of Ephesus and of Turkey's archaeological treasures: the Library of Celsus. While the Library is a monument which marks one of the happiest periods of Ephesus' history (it was built in 117 AD), Marble Street is an indication of its decline: it was rebuilt in the Vth century by using marble slabs from former temples and graves.

The Library was erected to celebrate Julius Celsus Polemenus, a Roman proconsul of Asia. The Byzantines used most of its decoration to build a fountain. The Austrian Archaeological Institute began excavations at Ephesus in 1895 and most of the monuments of the town have been uncovered and restored by Austrian archaeologists. Some of their findings were donated by Sultan Abdul Hamit II to Emperor Franz Joseph II. They are now on display at the Ephesos Museum of Vienna. In 1910 at the request of the Turkish government Austrian archaeologists dismantled the fountain and reconstructed the Library, a course of action which if followed in Rome would lead to pulling down Acqua Paola to rebuild Tempio di Minerva.

The ancient monuments are regarded as an integral part of the country's heritage by the Turkish government and those of Ephesus were depicted on banknotes.

On the 2001 banknote there is no evidence of a triumphal gate which gave access to the Lower/Commercial Agora and is situated immediately to the right of the Library. The scanty walls of 2001 became an imposing gate by 2006. The triumphal gate had been built to celebrate Emperor Augustus and Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, his son-in-law, by two liberti (freed slaves). It appears that Mazeus was a libertus of Augustus and Mithridates of Agrippa. They are not known to have held any office, but they might have served Agrippa when he resided at Lesbos, an island not very far from Ephesus, in 22 BC.

The gate gave access to a very large square courtyard surrounded by shops aligned along colonnaded porticoes. The 1st century AD agora was redesigned at the time of Emperor Caracalla. It was rebuilt by Emperor Theodosius making use of materials taken from other monuments, chiefly the Temple to Domitian, the Gymnasium of Vedius and another gymnasium near the Baths of the harbour.

The way inscriptions celebrating past emperors were treated shows how far Theodosius went in despising his predecessors. This was because they had followed the traditions which had been handed down to them since the foundation of Rome. Go to: Roman Ephesus: The Upper Town Byzantine Ephesus and St. John's Cathedral Ayasoluk (Selçuk) Archaeological Museum of Ephesus Clickable Map of Turkey showing all the locations covered in this website (opens in another window).     |