What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in December 2013. |

- "Castles" in the Desert - page one - "Castles" in the Desert - page one

(left: J. L. Burckhardt in Arab attire in a XIXth century engraving; right: the Treasury of Petra) If you came to this page directly you might wish to read an introductory page to this section first. Castles or palaces?

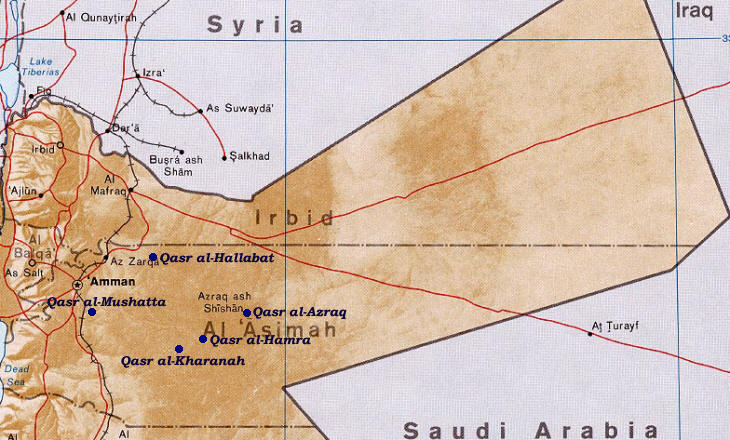

The "castles" are so called because they all have the appearance of a fortification as they are surrounded by walls with towers, but some of them were meant to be temporary residences where the Umayyad Caliphs received the leaders of Bedouin tribes or from where they went hunting. The most famous Umayyad "Desert Castle" is Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi (Western Castle) in Syria, sixty miles east of Palmyra. J. L. Burckhardt did not visit the locations covered in this page as they were too far from his route to Egypt. Qasr al-Hallabat

Qasr al-Hallabat was built as a leisure residence by the Umayyads on the site of a small Roman fort. A 212 AD inscription which mentions a novum castellum (new castle) suggests the fort was built during the reign of Emperor Caracalla, however, because the Umayyads brought in materials from other ancient sites, the inscription does not necessarily refers to Qasr al-Hallabat. Usually mosques are inside the enclosure surrounding the main building, but at Qasr al-Hallabat, the mosque was placed outside the walls, as if its presence would have been in contrast with what was going on in the castle.

Qasr al-Hallabat is situated on an isolated low hill which enjoys a commanding view in all directions. Notwithstanding the barren landscape shown in the image it is likely that the area to the west of the castle was farmed, at least until the VIIIth century. In 793-796 a series of conflicts among Arab tribes who had moved to Palestine and Transjordan had a devastating effect on the security of the region and on farming.

The castle was structured around a main courtyard and it had an elaborate system for capturing rainfall inside underground cisterns which conveyed water to a well in the main courtyard. A system of sluices has been found outside the castle in what was an agricultural enclosure.

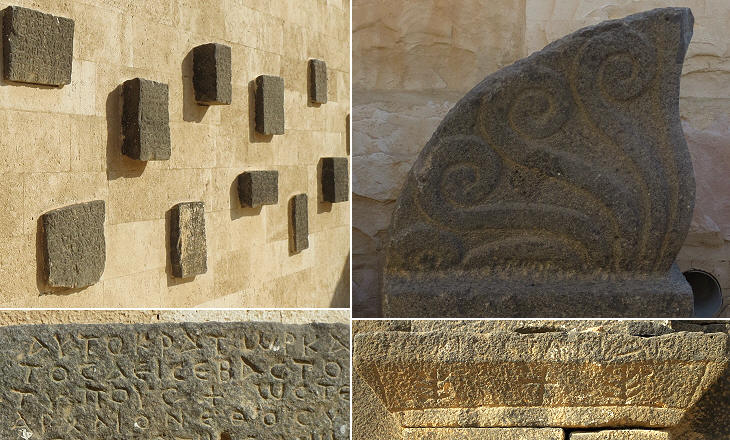

Almost all the rooms were decorated with mosaics which included the depiction of human beings. They recall those of late Byzantine churches such as St. Stephen's at Umm ar-Rasas. According to some scholars these mosaics were an attempt to utilize a local deeply rooted tradition in an Islamic context, similar to what the Umayyads had done at the Great Mosque of Damascus. Unfortunately most of a large mosaic in Room 11 which depicted an Islamic symbolic interpretation of the world was stolen in 1990.

The castle is built with a local limestone, but basalt stones were used for the towers. They came from Hauran, a region north of Qasr al-Hallabat and most likely from Umm al-Jimal, a town entirely built with basalt. 146 stones bear Greek inscriptions: most of them are part of the Edict of Anastasius I, Byzantine Emperor in 491-518, a document dealing with the military administration of the frontier provinces.

Qasr al-Mushatta

This palace is situated near the International Airport of Amman, but it does not receive the attention it deserves by those who organize tours of Jordan, although its design is an interesting example of the passage from classic to Islamic architecture. According to tradition it was built by Umayyad Caliph Walid II and it was never finished as the Caliph was killed after only one year in charge. The overall design recalls Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi as it had a pool at the centre of the courtyard and a mosque near the entrance.

Caliph Walid II had a very poor reputation among the most pious Muslims because of his dissolute lifestyle and his drinking. The design of the main hall of the palace, which most likely was where the Caliph had in mind to place his throne, indicates he regarded himself as a Byzantine emperor, disregarding the Muslim call for simplicity. The hall is divided into three naves, it is preceded by an arch and it ends with an apse, all features which can be found in early churches as at S. Prassede in Rome.

The decoration of the hall was entrusted to Byzantine sculptors and it recalls similar works at Qalb Lozeh and St. Simeon's Martyrion in northern Syria. Sculptors used drills much more than chisels. The decoration included mythological animals (some of which belonging to the Persian tradition) and human beings.

The ruins of the palace were discovered in 1840. A significant section of the remaining decoration of the entrance to the enclosure (it opens in a separate window) was given to German Emperor Wilhelm II as a gift from Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II just before World War I and today it is on display at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

An interesting feature of the palace is that it was partly built with baked bricks, something which was rarely done in Jordan, but was typical of Roman construction techniques, not only in Rome (you might wish to see the Temple to Serapis in Pergamum). Go to page two. Move to: Introductory Page Ajlun Castle and Pella (May 3rd, 1812) Amman and its environs (July 7th, 1812) Aqaba Jerash (May 2nd, 1812) Madaba (July 13th, 1812) Mt. Nebo and the Dead Sea (July 14th, 1812) On the Road to Petra (incl. Kerak and Showbak) (July 14th - August 19th, 1812) Petra (August 22nd, 1812) Umm al-Jimal Umm Qays (May 5th, 1812)

|