What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in February 2015. |

- Medieval Ravenna - Medieval Ravenna(Longobard weapons at Museo Archeologico di Cividale) You may wish to read an introduction to this section or see other pages on Ravenna (Roman monuments, Ostrogothic monuments, S. Apollinare in Classe, S. Vitale and Other Byzantine Monuments) first.

In the VIIIth century the Longobards put an end to Byzantine rule in Ravenna. Its Archbishops managed to be given power by the new rulers and to avoid being subject to the Roman Popes. In the following years the Franks defeated the Longobards and Charlemagne supported the Popes, but the Archbishops of Ravenna continued to fight to retain their authority. The canopy of S. Eleucadio indicates that they could rely on resources to embellish their churches. Its decoration is similar to canopies designed at Cividale during the Longobard rule.

The discontinuation of the drainage measures adopted by the ancient Romans to facilitate the emptying of rivers into the Adriatic Sea gradually turned the territory surrounding Ravenna into a swamp. This caused the sinking into the ground of some of its buildings. In some instances the floors were slightly raised, but in the case of S. Francesco a new church was built above the ancient one.

Classic architecture buildings did not include very tall towers with the exception of a few lighthouses, because towers which strengthened the walls were not much higher than the battlements. The Christian use of bells to indicate the beginning of ceremonies is traditionally dated Vth century, but the construction of campanili, isolated tall bell towers, became common only towards the end of the Ist millennium, perhaps as a Christian response to Muslim minarets. Those of Ravenna are among the oldest ones.

The round shape of its bell towers characterizes the skyline of Ravenna, but some of them had a square shape. A typical feature of both circular and square bell towers is that the number of openings increases at each storey in order to reduce the weight of the building (you may wish to see an imposing bell tower at Pomposa, near Ravenna). Because of the subsidence of the ground almost all the bell towers of Ravenna lean significantly.

In 1657 subsidence caused the collapse of S. Maria Maggiore, one of the oldest churches of Ravenna, which is located near S. Vitale. Its ancient circular design was not adopted in its reconstruction. The collapse might have impacted on the bell tower which is not as tall as one would expect considering that it is identical to the lower part of those at S. Apollinare in Classe and S. Apollinare Nuovo.

The church was dedicated to St. Peter before being assigned to the Franciscans in 1261. Its construction was promoted by the Archbishops who enjoyed the protection of the German Emperors and sided with them in the Investiture Controversy. In 1080 Archbishop Guiberto was elected (anti)Pope Clement III and for twenty years he led the opposition to Pope Gregory VII and his successors. The Archbishops of Ravenna maintained the Byzantine title of Exarchs (governors) until 1157.

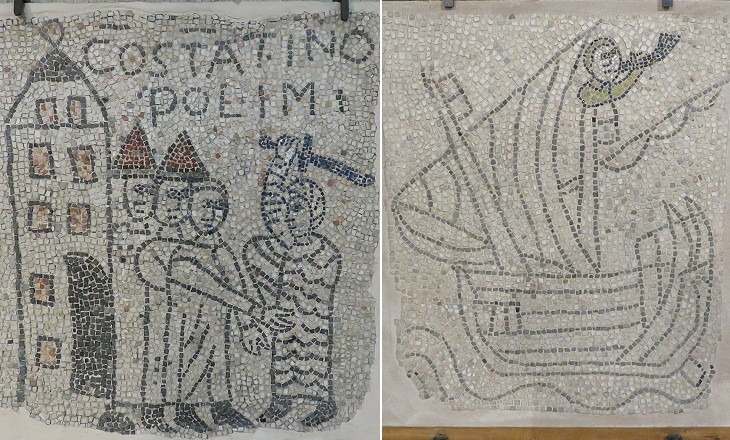

In the XVIIIth century a floor decorated with mosaics celebrating the conquest of Constantinople was unearthed at S. Giovanni Evangelista. Some of its panels are on display in the church. It is believed it was donated by a knight who participated in the Fourth Crusade to fulfil a vow. The church had been founded by Empress Gallia Placidia in the Vth century for the same reason: to thank St. John the Evangelist for her safe journey from Constantinople to Ravenna.

The panels at S. Giovanni Evangelista are one of the last examples of floor mosaics. They were replaced by inlays of marbles and coloured stones which are known as opus alexandrinum or Cosmati work. Mosaics continued to be used for decoration of apses and walls until the early XIVth century when frescoes began to be preferred for the depiction of complex scenes (you may wish to see some 1291 mosaics by Pietro Cavallini at S. Maria in Trastevere in Rome).

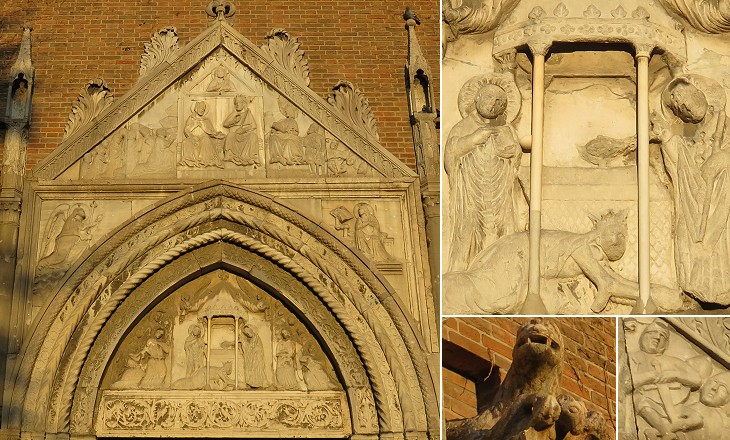

In the XIVth century the church was redesigned, but it retained the Vth century apse mosaics. These were destroyed when the church was bombed during WWII. The portal was decorated with reliefs showing Gallia Placidia and Emperor Valentinian III, her son, on his knees, with St. John the Evangelist. Valentinian was portrayed as a bearded medieval king and the scene recalls German Emperor Henry IV kissing the slipper of Pope Gregory VII at Canossa in 1077.

The power of the Archbishops was eventually replaced by that of the Da Polenta, a family of German origin. They initially held positions in the archbishopric administration, but in 1275 Guido da Polenta became the sole ruler of Ravenna. He gave his daughter Francesca in marriage to Gianciotto Malatesta of Rimini who had helped him seize power. The story had a tragic ending which was chanted by Dante who spent his last years at Ravenna at the court of the Da Polenta and died there in 1321.

The funeral of Dante took place in S. Francesco and the poet was buried near the church. In the XVIIIth century the urn with the bones of Dante was placed in a small mausoleum (it opens in another window). The da Polenta are best known for having hosted Dante and Giovanni Boccaccio at their court, but their fame is marred by their proclivity to family homicides. Ostasio I da Polenta killed one of his cousins and one of his uncles and he was most likely murdered by his own son who in turn starved his two brothers to death.

Notwithstanding the prestige of its past as capital of the Western Roman Empire, Ravenna declined during the rule of the da Polenta and gradually fell into the sphere of influence of Venice. In 1441 Ostasio III da Polenta was ousted from the town which became a direct Venetian possession. You may wish to move to: Roman Ravenna Ostrogothic Ravenna Byzantine Ravenna: S. Apollinare in Classe Byzantine Ravenna: S. Vitale Byzantine Ravenna: Other Monuments Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Walls and Gates Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Churches Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Other Monuments or go to: Introductory page Roman Aquileia - Main Monuments Roman Aquileia - Tombs and Mosaics Early Christian Aquileia Medieval Aquileia Chioggia: Living on the Lagoon Chioggia: Churches Chioggia: Other Monuments Roman and Medieval Cividale del Friuli Venetian Cividale del Friuli Grado Palmanova Roman and Byzantine Parenzo (Porec) Medieval and Venetian Parenzo (Porec) Roman Pola (Pula) Medieval and Venetian Pola (Pula): Churches Medieval and Venetian Pola (Pula): Other Monuments Pomposa Rovigno (Rovinj) Roman and Medieval Trieste Modern Trieste     |