What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in January 2015. |

- Byzantine Ravenna - Other Monuments - Byzantine Ravenna - Other Monuments(Longobard weapons at Museo Archeologico di Cividale) You may wish to read an introduction to this section and pages on Roman and Ostrogothic Ravenna first. S. Apollinare in Classe and S. Vitale, the two main churches built during the Byzantine period are covered in separate pages.

Of his palace at Ravenna perhaps nothing is left. The building that goes by that name is of doubtful origin, and even if it be part of the palace it is uncertain to what part of the establishment it belonged. It is ornamented, though in a more barbarous fashion, with the miniature colonnading which first appeared at the Porta Aurea of Diocletian at Spalato. Thomas Graham Jackson - Byzantine and Romanesque Architecture - 1913 There is still uncertainty about the purpose of this brick building which is situated next to S. Apollinare Nuovo. It could have been the narthex (initial section) of a lost church or a barracks for the guards of the Exarchs, the governors of the Byzantine territories in Italy.

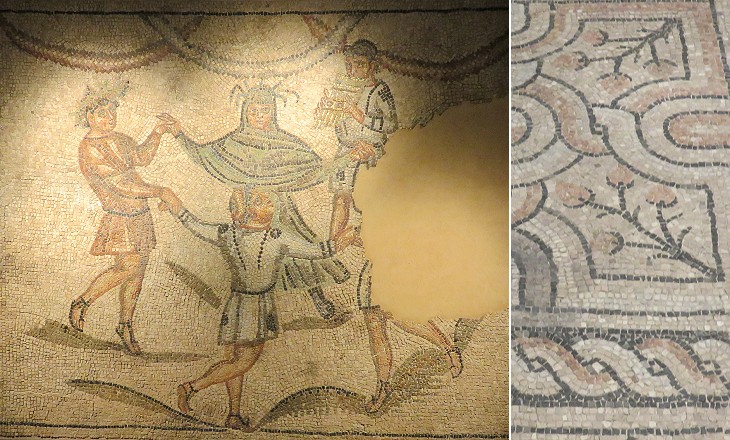

A series of ancient floor mosaics were identified in 1994 in the course of excavations for opening an underground parking garage near S. Vitale. They belong to different periods, but the largest and finest ones decorated a VIth century rich house arranged around three courtyards. In 2000 the site was opened to the public and it provides visitors with an understanding of a different kind of Byzantine mosaic than that for which Ravenna is best known.

The Four Seasons were a very popular subject of Roman floor mosaics, but they were usually utilized to fill the corners of a large square mosaic as one can see at the Museum of Bardo in Tunisia. In this mosaic at Ravenna they were portrayed in a very unusual way in a small central panel. The traditional symmetrical representation of the Seasons was abandoned for a lively scene with a fifth figure, a musician playing a pan flute.

You may wish to compare these mosaics with those of the Basilica of Aquileia which belong to the IVth century.

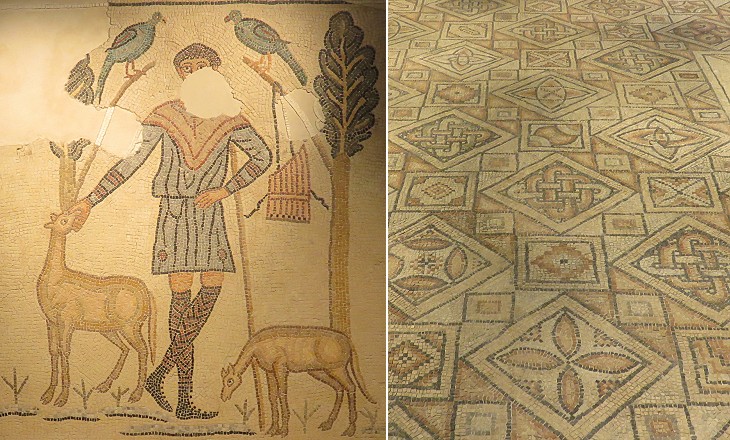

The Rasponi were one of the wealthiest families of Papal Ravenna. In 1819 Lord Byron was urged by Countess Teresa Guiccioli, of whom he was the official cicisbeo (gallant and lover of a married woman), to write a Sonnet On The Nuptials Of The Marquis Antonio Cavalli With The Countess Clelia Rasponi Of Ravenna (it opens in another page - external link). The Rasponi decorated a chapel of one of their palaces with VIth century mosaics taken from the lost church of S. Severo in Classe. The result is a poor patchwork because they used only fragments depicting animals which were arranged to suit the layout of the chapel. The palace was eventually acquired and modified by the Italian State and today the chapel is open to the public.

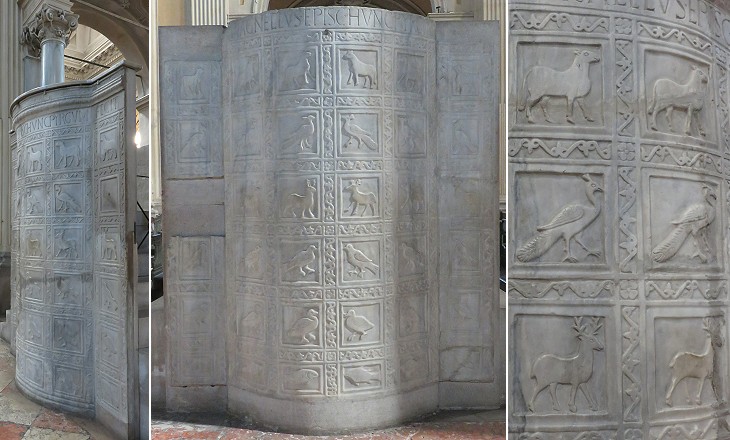

The remains of the marble ambo of the Ursian basilica is decorated by panel-work with a little bird or beast in each compartment. T. G. Jackson The Cathedral was built at the same time as the adjoining Neonian Baptistery, but it was entirely redesigned in the XVIIIth century. It retains however a VIth century ambo decorated with very flattened reliefs, undoubtedly showing Byzantine influence, and a number of ancient sarcophagi. The adjoining Archiepiscopal Palace includes a chapel with fine mosaics and a small museum. Taking photographs is not allowed, but some images can be seen in this website (it opens in another window).

One sort of sculpture seems certainly to have been practised at Ravenna, that of making the marble sarcophagi of which so many still remain there. T. G. Jackson There are very many sarcophagi in Rome, but they rarely retain their lids, as they were often reutilized for small fountains inside the courtyards of palaces. At Ravenna instead they continued to be used as tombs and they retain their lids, although in some instances the lid is not the original one.

The most common type of lid is shown above (you can see a similar one at Thassos in Greece - it opens in another window or Sepolcro di Nerone in Rome), but in Lycia, in southern Turkey, a different type of lid was developed (see at Patara the two lids side by side).

At Ravenna the "Lycian" lid was given a semicircular shape and it is characteristic of most sarcophagi. It was usually decorated with three elaborate crosses. Italian art historians call this type of sarcophagus a bauletto, because it recalls a small travelling case (It. baule).

This sarcophagus, similar to many others, was used as a grave for an Archbishop of Ravenna. In most cases the sarcophagi were kept outside the churches. Their location might have influenced the design of Tempio Malatestiano at Rimini where sarcophagi were planned to be placed alongside the building.

In many Early Christian reliefs and mosaics at Ravenna palm trees are shown at the sides of a scene. Their ripe fruit is very noticeable because one of the reasons the tree was so often depicted is that dates ripen even when the trunk is very old and apparently dead. Thus the dates were regarded as a symbol of the Resurrection.

The reliefs decorating Roman Pagan sarcophagi tended to be very crowded and in some instances up to thirty figures were depicted. In addition the figures projected in a significant way and often overlapped (see a sarcophagus at Bolsena). The sarcophagi at Ravenna retained this tradition of realistic depiction to a much lesser extent with only a limited number of rather flat figures.

The lower part of the sarcophagus is dated early Vth century. The fact that it was utilized again in the VIIth century and for a very important person (Isacius was Exarch for eighteen years) seems to indicate that both resources and skills were no longer available in Ravenna. The new lid does not perfectly match the lower part and it was most likely made by using a broken column.

This is another example of sarcophagus which was given a new lid. It was found at Classe and moved near S. Francesco where it was bought by the Pignata, a XVIth century wealthy family, who turned it into their own tomb. It owes its name to the tradition saying it housed the relics of Prophet Elisha.

Dating these sarcophagi is not very easy because some of their inscriptions are misleading as they refer to a second use. The sarcophagi of Ravenna are decorated on all their four sides, which indicates they were not placed against a wall or inside a niche.

You may wish to move to: Roman Ravenna Ostrogothic Ravenna Byzantine Ravenna: S. Apollinare in Classe Byzantine Ravenna: S. Vitale Medieval Ravenna Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Walls and Gates Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Churches Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Other Monuments or go to: Introductory page Roman Aquileia - Main Monuments Roman Aquileia - Tombs and Mosaics Early Christian Aquileia Medieval Aquileia Chioggia: Living on the Lagoon Chioggia: Churches Chioggia: Other Monuments Roman and Medieval Cividale del Friuli Venetian Cividale del Friuli Grado Palmanova Roman and Byzantine Parenzo (Porec) Medieval and Venetian Parenzo (Porec) Roman Pola (Pula) Medieval and Venetian Pola (Pula): Churches Medieval and Venetian Pola (Pula): Other Monuments Pomposa Rovigno (Rovinj) Roman and Medieval Trieste Modern Trieste     |