What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in January 2015. |

- Roman and Byzantine Parenzo (Porec) - Roman and Byzantine Parenzo (Porec)(Longobard weapons at Museo Archeologico di Cividale) You may wish to read an introduction to this section first.

Parenzo, like Rovigno and many other of the old maritime cities on these coasts, is built on a peninsula, a situation at once secure and convenient, and one for which the indented coast both of Dalmatia and Istria affords many opportunities. The peninsula of Parenzo is flat and the city lies low (..); its front towards the sea, with the remains of the old town walls and an irregular line of houses and loggias, is not without its attractions. Sir Thomas Graham Jackson - Dalmatia, the Quarnero and Istria - 1887 Sir Thomas Graham Jackson (1835-1924) was one of the leading architects of his time. He visited Parenzo in 1885 and he wrote a very detailed account of its Euphrasian Basilica. At that time Parenzo was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1908 F. Hamilton Jackson noted in The Shores of the Adriatic: There were temples to Mars and Neptune, of which there are some remains, drums of a few of the columns and a portion of the podium and steps, now used as the lower courses of poor houses. The houses were eventually pulled down to free their ancient parts.

Similar to Pola, Parentium became a Roman colony at the time of Emperor Augustus. It did not have a large natural harbour, but the Romans improved it by building a long breakwater (now under sea level), so that it could be used as a base by Classis Ravennatis, their fleet stationed at Classe, the harbour of Ravenna. The "Great Temple" was built by a vice-commander of Classis Ravennatis in the late Ist century AD.

Here and there the eye lights upon a fragment of Roman work. But there is little of Roman Parentium above ground. T. G. Jackson. The layout of Parentium is still evident in that of modern Parenzo which is crossed by a straight east-west street ending at the site of the ancient Forum of Mars, perhaps a Campus Martius (Field of Mars), a military training ground.

There was a Christian church at Parenzo on the same site before the present duomo was built, but (..) no traces remain above ground of anything precedent to the work of Euphrasius, the first bishop. About 535 he began to build his cathedral church, and the date of its completion is supposed to be fixed in 543. (..) It is entered through an atrium or cloistered forecourt, but has to the west of the atrium the appendages of an octagonal baptistery and a campanile. T. G. Jackson Today the construction of the Basilica is set between 543 and 554, after the Byzantines had taken Parenzo from the Ostrogoths.

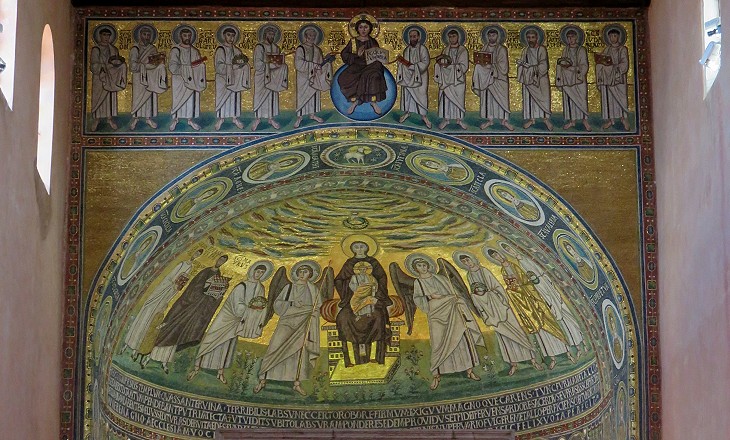

Crossing the threshold, one might almost fancy oneself on the opposite shore of the Adriatic in the old capital of Theodoric and the exarchs (Ravenna). There are the same closely-set ranks of marble columns, and the same delicately crisp acanthus leaves in the capitals, and the view is bounded by a magnificent mosaic that may challenge comparison with those of S. Apollinare in Classe and S. Vitale. The church of Parenzo is inferior to those of Ravenna in size alone. T. G. Jackson

His monogram meets the eye in every part of the building; it is over the great western doorway, in the mosaics of the drum of the apse, and on the impost blocks (see those at S. Giovanni Evangelista at Ravenna) of the nave columns. (..) many of the capitals might have been carved by the same hand that wrought those at S. Vitale or S. Apollinare in Classe and the workmanship is marked by delicacy and refinement.(..) The arches are round, and those in the north arcade are decorated with coffered ornaments modelled in stucco, which Prof Eitelberger (Rudolf Eitelberger 1817-85, Austrian art historian) attributes to the time of the renaissance, but which from the analogy of stucco-work of undoubted antiquity at Ravenna and elsewhere in this very church are more probably part of the original design. T. G. Jackson

(The apse mosaic) is positively claimed as the work of Bishop Euphrasius by the following excerpt from the inscription of four lines in the mosaic of the great apse: "HOC FVIT IN PRIMIS TEMPLVM (..) PROVIDVS ET FIDEI FERVENS ARDORE SACERDVS EVFRASIVS S(an)C(t)A (..) FUNDAMENTA LOCANS EREXIT CULMINA TEMPLI" (..) The purport of the inscription is that Euphrasius pulled down a humble and ruinous church, and built a new one from the foundations, which he decorated with mosaic and consecrated to Christian worship. T. G. Jackson By comparing this lengthy inscription with that which Bishop Theodore placed in the hall he built at Aquileia in 315, one can measure how much the importance of bishops had grown in two centuries. Theodore wrote: Happy Theodore, who, by the help of God and of the flock Heaven gave him, was able to complete and dedicate this church. Euphrasius instead took all the credit to himself for having built the basilica. While Theodore wrote his name on the floor, Euphrasius did it in a much more evident position.

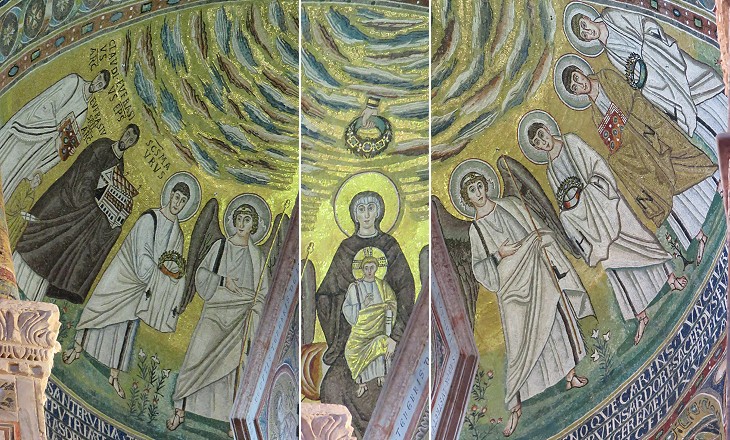

The Virgin Mary occupies the centre, clothed in a purple mantle and white undergarment embroidered with gold, and with her head encircled by a nimbus. The infant Saviour is dressed in white and gold, and holds a roll in one hand and raises the other in the attitude of blessing. From the sunset-tinted clouds above emerges a hand holding a jewelled wreath or crown. On each side of this central group is an angel, and beyond the angel three large figures. Those to the left have their names written, CLAVDIUS ARC. being the extreme figure, holding a book; next to him comes EUPHRASIUS EPS. with a small figure of his son and then SCS. MAURUS holding a jewelled urn. The bishop holds his church, a three-aisled basilica with one apse resembling the actual building, and wears a purple robe reaching below the knee; the rest are dressed Roman fashion in white with a purple stripe like the figures at Ravenna, though with certain slight differences. The three figures of saints on the other side of the central group have no names: one bears a book and the other two bear crowns. T. G. Jackson

The whole mosaic is finished next the opening into the nave by a wide border (..) on which are medallions within wreaths, each containing the head and bust of a female saint with her name. At the crown of the arch within a circle is the monogram, though now only in painted plaster, the mosaic having perished. T. G. Jackson The painted monogram was replaced by a modern mosaic representing God's Lamb and it is likely the whole section was poorly restored because Jackson mentioned medallions within wreaths, rather than circles. He did not mention the mosaic above the apse which was covered by plaster. It portrays the Apostles with St. Peter and St. Paul at the sides of Jesus Christ in Majesty. The subject recalls similar portrayals of the Apostles at the Neonian and Arian Baptisteries of Ravenna and the figure of Jesus is identical to that in the apse of S. Vitale. It is hard to say whether the mosaic above the apse is the result of a proper restoration or just a modern Ravenna-like work, but the latter possibility seems more probable.

On the wide wall spaces beyond the windows are figure subjects, the Salutation of Mary and Elizabeth on the south side and the Annunciation opposite it on the north. The angel Gabriel has a jewelled crown with flowing ribbons, and wears a white tunic with purple clavus (band) and a white toga which flutters behind him; the Virgin sits in the doorway of a building like a basilica, and has two gold stripes on the front of her dress from shoulder to foot. In the Salutation the costumes are similar; the breasts of both figures are marked by a strong line, and a little figure dressed in blue with a gold stripe peeps out from the half-raised curtain of a doorway behind Elizabeth. T. G. Jackson

The seats for the bishop and his presbyters which surround the apse at the base of the wall are of a white and veined marble resembling cipollino (..). Above the seats the walls are lined with a gorgeous dado of marbles and porphyries which has no parallel at Ravenna (..). The materials are porphyry, serpentino (or "verde antico", a green porphyry often used in Cosmatesque decorations as at Civita Castellana), opaque glass, white onyx like that from Algiers, burnt clay of various colours, and mother-of-pearl, which is used not only in mosaic but in discs made of whole shells, which reflect a brilliant opalescent light. There are eight varieties of pattern in the panels, and these are arranged symmetrically in pairs on the opposite sides of the apse; while the central panel over the bishop's seat is inlaid with a gold cross on a ground of serpentino and mother-of-pearl surmounting a hill or dome between two lighted candlesticks. (..) The whole dado is finished by a cornice of acanthus leaves moulded in stucco, which runs round the apse and is also of the original date. T. G. Jackson

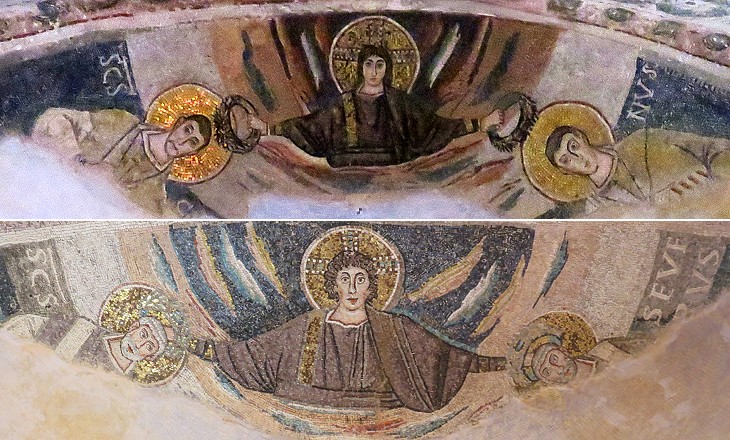

The two side naves ended with small apses where fragments of mosaics were discovered after Jackson visited Parenzo. These fragments have not been modified by modern poor restorations. That portraying Jesus with the two saints from Ravenna is stylistically more similar to the apse mosaics, than the other one. It is interesting to compare the depiction of purple clothes at Parenzo versus the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna which was built a century earlier. In the latter purple was used (and to a limited extent) only in The Good Shepherd mosaic. Purple clothes and porphyry acquired such a relevance as symbols of imperial power that in the Xth century deliveries of Byzantine Empresses took place in a special room entirely decorated with porphiry. As a matter of fact it was Emperor Diocletian, the fiercest persecutor of the Christians, who forbade the use of purple cloth to all but the emperors.

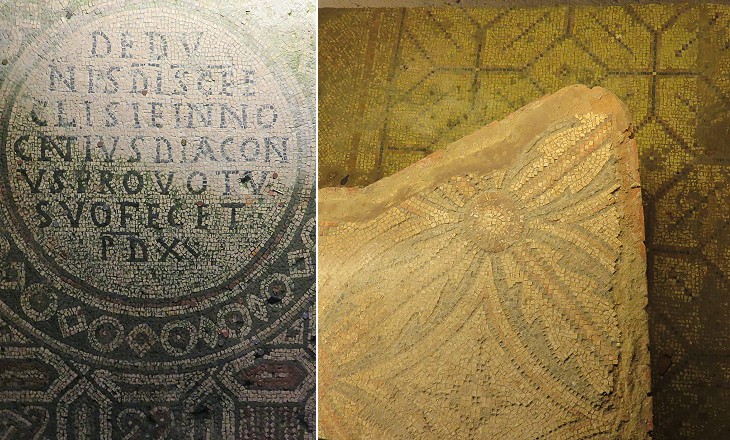

Twice during Christian times has it been found necessary to raise the level of the floor of the church. Professor Eitelberger describes the nave floor as lying two steps below that of the aisles, a very common plan in churches of this style and date, and as being paved with an ancient mosaic of red, black and white tesserae, which must have resembled that still existing at Grado. All this has now disappeared; the sea used to invade the church, the nave floor was raised in 1881 to the level of that of the aisles, and the pavements were buried, only a few miserable fragments having been taken up, which are stored for the present in one of the chapels. But it is still more surprising to learn that at the depth of two feet nine inches below what was the level of the nave when Eitelberger saw it exists another mosaic pavement, of which a sample has been dug up and is for the present stored away with those first named. This lower pavement extends also under the three chapels and part of it may be seen by raising a trap-door. It is of more geometrical design and somewhat coarser execution than the upper pavements, and looks like late Roman work. That this should ever have been the pavement of Euphrasius' basilica seems impossible, for the bases of his columns stand well above the upper floor level, and it is more probably the pavement of the preceding church which he pulled down. T. G. Jackson

The ingenuity of antiquaries has been much exercised by the curious group of little chapels which are entered from the north-east corner of the duomo. The first is a low groined rectangular chamber, with a row of central piers. From this a plain square doorway with a descent of two steps leads to a second chamber (..) From this another door leads to the third and last chapel (Cappella di S. Andrea), a square with three apses to north, east, and south. The two last chapels have considerable remains of beautiful mosaic pavements T. G. Jackson

Bishop Euphrasius stated in the inscription in the apse that he had built the basilica on the site of a previous church which was about to ruin. Archaeologists have found evidence of previous buildings and of a large mosaic floor. There are different opinions about dating and purpose of these buildings.

See Medieval and Venetian Parenzo or move to: Introductory page Roman Aquileia - Main Monuments Roman Aquileia - Tombs and Mosaics Early Christian Aquileia Medieval Aquileia Chioggia: Living on the Lagoon Chioggia: Churches Chioggia: Other Monuments Roman and Medieval Cividale del Friuli Venetian Cividale del Friuli Grado Palmanova Roman Pola (Pula) Medieval and Venetian Pola (Pula): Churches Medieval and Venetian Pola (Pula): Other Monuments Pomposa Roman Ravenna Ostrogothic Ravenna Byzantine Ravenna: S. Apollinare in Classe Byzantine Ravenna: S. Vitale Byzantine Ravenna: Other Monuments Medieval Ravenna Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Walls and Gates Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Churches Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Other Monuments Rovigno (Rovigno) Roman and Medieval Trieste Modern Trieste     |