What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in March 2015. |

- Palmanova - Palmanova(Longobard weapons at Museo Archeologico di Cividale) You may wish to read an introduction to this section first.

The first stone of the city-fortress of Palmanova was laid on October 7, 1593, the feast of St. Justina of Padua and twenty-second anniversary of the Battle of Lepanto, in which the fleet of a Christian coalition defeated the Ottoman one. The inscription under the statue of St. Justina says Victoriae auspici (supporter of victory). The decision by the Venetian Senate to build Palmanova was therefore justified as an anti-Ottoman defensive measure.

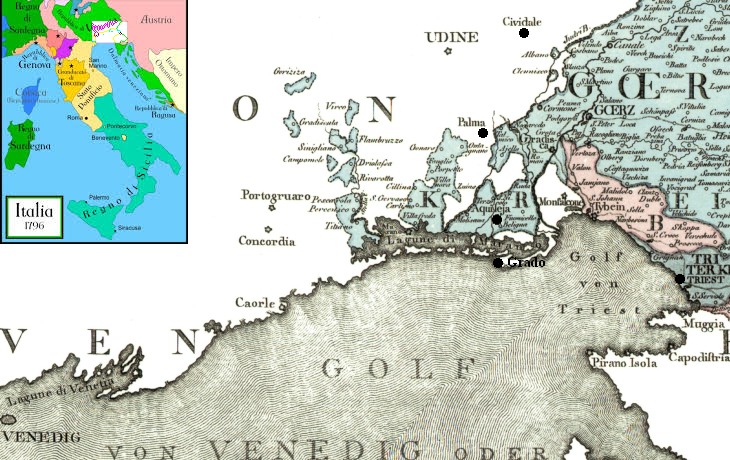

The map shows that the fortress of Palmanova was actually meant to strengthen the defence of the territories of the Republic bordering on the Archduchy of Austria. The boundary line was very indented, with a number of small Austrian fiefdoms inside Venetian territory (they had belonged to the Patriarchate of Aquileia). When Palmanova was founded relations with the Ottoman Empire were relatively good, whereas those with the Archduchy of Austria were often tense. They deteriorated to such a point that in 1615-17 an undeclared war was fought for the possession of Gradisca, a fortress near Palmanova.

The design of Palmanova was entrusted with Giulio Savorgnan, a military commander and architect who had fortified Nicosia on the island of Cyprus in the late 1560s with walls having eleven bastions. He used the same approach at Palmanova but he reduced the number of bastions to nine, while maintaining the same number of gates (three) as at Nicosia.

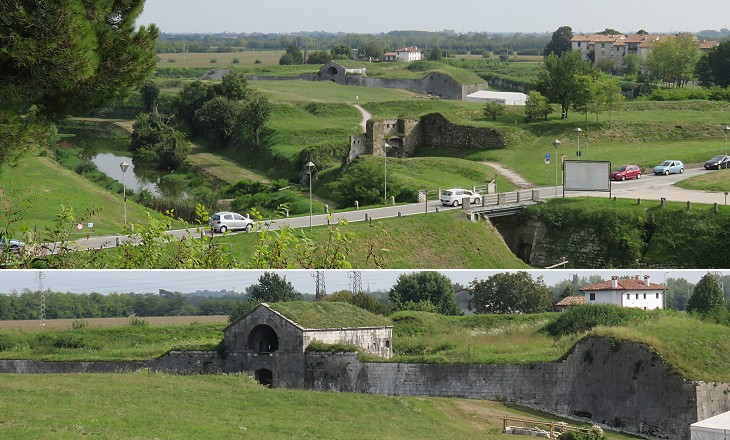

The walls of Palmanova had to be very wide in order to neutralize attempts to blow them up, because the enemy would dig tunnels to place and ignite charges of gunpowder at their base. They were made up of two curtain walls which were filled with earth. Today they provide the inhabitants of Palmanova with a large public footpath which entirely surrounds the town.

The need to fire on enemies from a side position led military architects to design bastions which projected from the walls as Francesco di Giorgio Martini did in 1475 at San Leo. Eventually Italian military architects came to the conclusion that an arrowhead shape was the most appropriate one and Palmanova had arrowhead bastions similar to those which the Venetians had already built at Candia and the Knights of St. John at Valletta (Malta).

The protection granted by the walls was complemented by a wide moat and a number of ravelins, triangular external fortifications which made up a sort of second enclosure. In 1806-11 the French added nine lunettes, advanced bastions having a half-moon shape.

Venetian military architects usually placed gates in a side position which was protected by a bastion as they did in 1595 at Asso, a fortress in Greece. At Palmanova however Marcantonio Barbaro, the first Provveditore (governor), requested Savorgnan to design a grand entrance to the city-fortress. In addition he did not want obstacles to be placed behind the gate which therefore gave direct access to the centre of the town.

The other two gates were completed shortly after Porta Aquileia. Their design is very similar and it follows a pattern established by Micheli Sanmicheli at Forte S. Andrea in Venice. An aqueduct provided Palmanova with an ample supply of water which could be stored in large cisterns in case of siege.

Straight streets linked the three gates to the main square. They were very wide according to the standards of the time and they were meant to provide those who arrived at Palmanova with a maravigliosa vista (beautiful view) of the town. Military requirements were neglected in order to design the "ideal city" many Renaissance architects and painters dreamed off.

The heart of Palmanova was a very large hexagonal square which was used as a Field of Mars where the troops exercised. It had a diameter of 100 Venetian paces (190 yards). On July 22, 1602 the standard of the Republic was flown on a very high flagpole placed above the fountain of the town at the centre of the square.

Venetian authorities expected Palmanova to become a large town with a sizeable population, but this did not happen and the trade fairs which were introduced in 1622 did not attract merchants. The only activities were related to the garrison. A 1706 census recorded a population of only 6,000 inhabitants. Palmanova did not have local noblemen and only a couple of convents. The inscriptions and coats of arms which decorate some buildings are all related to the military.

In addition to the three streets leading to the gates, three other streets departed from the main square. At the beginning of each street statues celebrating a provveditore were erected. This practice was stopped in 1691 by the Venetian Senate. The incumbent provveditore did not remove the statues, but erased the coats of arms and inscriptions on their pedestals. Several attempts have been made to identify the provveditori portrayed in the statues, but only for a few of them the identification is certain, because faces and costumes correspond to known portraits of them. They show the changes in fashion which took place in Venice during the XVIIth century; wigs made their appearance in Venice in ca 1665, after their use was made fashionable by King Louis XIV of France.

At the beginning of 1797, during the War of the First Coalition (the European Monarchies against Revolutionary France), the Republic of Venice decided not to prevent the French and Austrian armies from entering its territories and fortresses. In March Napoleon Bonaparte and his troops entered Palmanova which was not defended by the Austrians who had occupied it. On May 1 Napoleon declared war on the Republic of Venice and on its symbol, the Winged Lion of St. Mark. Some 5,000 statues and reliefs were smashed by the French and their local supporters. The image used as background for this page shows a XIXth century copy of the Winged Lion on the Duomo of Palmanova. Derogatory inscriptions towards the supporters of the "Ancien Régime" (Old Order) were written on the pedestal of the flagpole which was replaced by a French Tree of Liberty.

Today Palmanova has slightly less inhabitants than it had in 1706. Apart from the replacement of the drawbridges with modern ones and the pulling down of ravelins opposite the gates, the fortifications of Palmanova retain the aspect they had in the XVIIth century. Move to: Introductory page Roman Aquileia - Main Monuments Roman Aquileia - Tombs and Mosaics Early Christian Aquileia Medieval Aquileia Chioggia: Living on the Lagoon Chioggia: Churches Chioggia: Other Monuments Roman and Medieval Cividale del Friuli Venetian Cividale del Friuli Grado Roman and Byzantine Parenzo (Porec) Medieval and Venetian Parenzo (Porec) Roman Pola (Pula) Medieval and Venetian Pola (Pula): Churches Medieval and Venetian Pola (Pula): Other Monuments Pomposa Roman Ravenna Ostrogothic Ravenna Byzantine Ravenna: S. Apollinare in Classe Byzantine Ravenna: S. Vitale Byzantine Ravenna: Other Monuments Medieval Ravenna Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Churches Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Walls and Gates Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Other Monuments Rovigno (Rovinj) Roman and Medieval Trieste Modern Trieste     |