What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in January 2015. |

- Grado - Grado(Longobard weapons at Museo Archeologico di Cividale) You may wish to read an introduction to this section and some pages on Aquileia first.

Beyond Aquileja the flat alluvial plain which is barely raised above the sea-level is intersected by numerous small canals, which gradually run together into larger channels, and finally debouch into wide lagunes protected by narrow sand-banks from the open sea. On one of these natural breakwaters is situated the ancient patriarchal city of Grado, washed on the outer side by the Adriatic, and on the inner by the shallow waters of the lagune.(..) The town of Grado never recovered the havoc of Poppo's double invasion (Poppo, Patriarch of Aquileia, seized and sacked Grado in 1024 and 1044); and from that time it steadily declined till it became what we now see it, a mere village on a desolate island, with nothing but the ancient basilica to mark its former ecclesiastical importance as the seat of the Venetian primate. (..) What Grado now is, Venice once was, and there was a time, difficult as it now is to realise it, when Grado was the superior and Venice the inferior place of the two. But Grado has lately awakened from the condition of a city of the dead, and taken a new lease of life as a watering place. The sloping sandy beach offers facilities for bathing which are rare on the rocky and tideless shores of the Adriatic; and during the summer visitors come in hundreds from Gorizia and the other towns of Friuli. Sir Thomas Graham Jackson - Dalmatia, the Quarnero and Istria - 1887 Sir Thomas Graham Jackson (1835-1924) was one of the leading architects of his time. He visited Grado in 1885 and he wrote a very detailed account of its Patriarchal Basilica. At that time Grado was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Reaching the island we entered a straight canal between embankments which led to the port, a tolerably capacious basin full of gaily-painted boats from Chioggia. (..) A cluster of houses here and there and a few solitary campaniles mark the situation of the little villages where these fisher-folk have their homes; San Pietro in Orto, now nearly deserted, with only a campanile left to serve for a landmark; Belvedere, where the mainland ends at the edge of the lagune, and where it is said the Roman arsenal was situated; and Barbana (which you can see in the introductory page), where in a deserted convent there is a miraculous Madonna, visited every year by thirty or forty thousand pilgrims, who come in thousands at a time, and pass the night in boats, in the empty convent, or out of doors, as luck will have it. T. G. Jackson

Beyond the port lies the city, a cluster of shabby houses divided by a network of intricate and narrow alleys, in which, small as the place is, one may easily contrive to lose one's way. The houses, though innocent of paint and somewhat dilapidated, are not badly built, and, as at least every alternate house of those that surround the harbour is an inn, a caffe, or a trattoria, there is no difficulty in finding a lodging. (..) The situation is very healthful, and there is no talk here of ague as on the mainland. T. G. Jackson

Grado was founded in the IIIrd/IVth century AD to serve as the new port of Aquileia, because the city harbour on the River Natisone was no longer capable of handling large ships. The layout of the town is roughly rectangular in line with Roman practices and Calle Lunga, the street which crosses the town from the lagoon harbour to the sea front, is the ancient cardo maximus, the main north-south street of Roman towns.

The Duomo of Grado has not, I believe, been described, nor so far as I know had it been seen by any English student of architecture at the time of my first visit. (..) It was therefore with the excitement of explorers, not knowing what we should find to reward our journey, that we at last stood before the patriarchal basilica, after more wrong turns and mistakes than might have been thought possible in so tiny a city. The exterior as usual has little to recommend it. T. G. Jackson In 452 Attila the Hun set fire to Aquileia and the Bishop with many inhabitants of the city sought refuge in Grado. In ca 454 Bishop Niceta built two churches next to each other along the main street, similar to the halls built by Bishop Theodore at Aquileia in 315. These two churches were both replaced by larger ones (S. Maria delle Grazie and the Cathedral) after 568 when other refugees moved to Grado as a consequence of the Longobard invasion of Italy.

Externally the church is naught; but, the threshold once passed, the interior bursts on the view with surprising effect. The wide nave with closely-set ranks of marble columns on either hand carrying narrow semicircular arches, and the apse which bounds the view eastward, proclaim the church a basilica of the same class with S. Apollinare Nuovo at Ravenna, and the Euphrasiana at Parenzo. Here it is true there are no glittering mosaics on the walls, but this is compensated by the surpassing splendour of the columns of bianco e nero (black and white) marble, and the beauty of the mosaic pavements which cover the nave floor. Nor is there anything in either of the other churches so surprising as the strange pulpit at Grado, raised on lofty pillars, with rudely sculptured emblems on its embowed sides, and surmounted by a painted canopy or dome so oriental in its appearance that it would not seem out of place in a Mohammedan mosque.(..) The first view of the interior of Parenzo is perhaps more impressive than that of Grado, though the latter church is considerably the larger of the two; but there is about the interior of the Gradensian basilica a quaintness and strangeness in excellent keeping with its remote and inaccessible situation, shut out by lagunes and swamps from the ordinary haunts of mankind, a home and nesting-place for sea-fowl (*). (..) Restorations were probably confined to interior fittings and decorations, with but little effect on the main fabric, which for the most part has every appearance of being the actual church built or restored by Helias towards the end of the sixth century. T. G. Jackson (*) In 537 Cassiodorus, a Roman statesman who served in the administration of King Theodoric, in a letter to the inhabitants of the lagoons north of Ravenna wrote: Hic vobis aquatilium avium more domus est. (Here - on the lagoon islands - you have fixed your home after the manner of the waterfowl.)

On each side are eleven arches carried by marble columns. The shafts are probably all antiques taken from Roman buildings (..). I do not remember ever to have seen more splendid marble columns than these. The pulpit consists of two parts belonging to widely different periods. The lower part, consisting of the pulpit itself and the six columns that carry it, is of white marble and of Byzantine or Romanesque work. (..) The pulpit above, raised nearly seven feet above the pavement, is a sexfoil in plan, except that one side is interrupted for the entrance. Four of the sides are carved with the four beasts of the Apocalypse (rather the symbols of the Evangelists) (..); and on the fifth side towards the east is a large cross. This church seems to have been renovated if not rebuilt by the patriarch Helias whose episcopate lasted from 571 to 586. A coeval inscription still existing in the mosaic pavement speaks of the preceding church as decayed by age, and commemorates its restoration in a magnificent manner by this patriarch of New Aquileia. T. G. Jackson In 571 Grado became the official see of the Patriarchate of Aquileia.

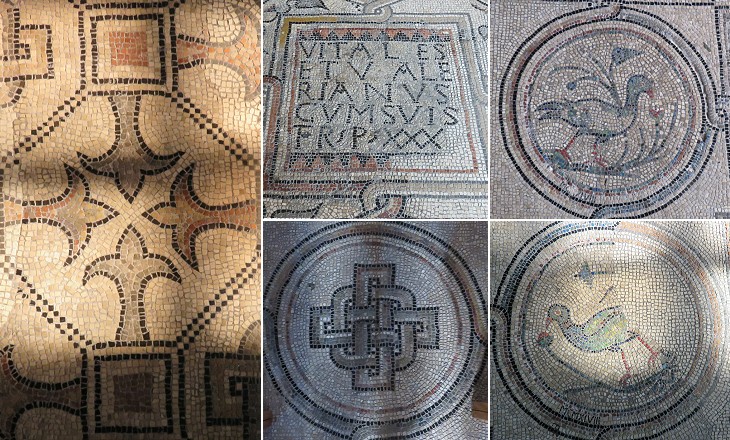

The ancient mosaic pavements of Grado will perhaps make as strong an impression on the visitor as any other feature of the church. They seem at first sight to extend over the whole area of the nave, under the seats as well as in the middle passage; and although a large part of the mosaic proves on further inspection to be ordinary modern work, still enough of the old remains to give the entire design, and no other church of the date has so well preserved its original flooring. (..) The pavements are, like those of classic times, composed entirely of tesserae; there are no geometrically shaped pieces as in the later pavements of "opus Alexandrinum" such as those at S. Maria in Cosmedin at Rome (..). Everything is done with small cubes of half an inch or less, set to an admirably close joint, which the restorers and imitators of modern times have in vain tried to copy. (..) The general arrangement is very simple; a broad walk runs up the centre, interrupted here and there by square spaces with inscriptions. (..) Right and left of this walk the pavement consists of square panels divided by borders, the panels being filled either with geometrical patterns on a white ground or with inscriptions. The inscriptions are very numerous and curious, and give a special character to the work. It is unusually interesting to find one of them in Greek, side by side with others in Latin, a fact significant of the political position of Grado on the borderland of Eastern and Western Europe. They all, whether Greek or Latin, abound in grammatical mistakes and blunders of spelling. (..) The purport of the inscriptions is to record donations of a part of the pavement, generally in pursuance of a vow; and many of them state the number of feet included in the gift. Laurentius heads the list with two hundred or perhaps seven hundred feet; Nonnus and Eusebia, Peter and John, servants of the holy martyr Euphemia, give amongst them a hundred feet; others give thirty-five feet; and several, among whom appears Guderit who must be a Goth or a Lombard, give each twenty-five feet, which is about equal to one square compartment with its enclosing border. T. G. Jackson

Close by the duomo, on the north side, not as usual in early churches opposite the west end, is the baptistery, a spacious octagon with an apse projecting from its east side. It has been recently restored, and is now perfectly plain and devoid of architectural features. In the small piazza to the north of the duomo and in front of the baptistery are arranged three sarcophagi which were dug up on the spot, and which, though originally Pagan as the inscriptions prove, were probably appropriated for the sepulture of Christian patriarchs. T. G. Jackson

There are other churches at Grado besides the duomo, but none whose exterior is of a kind to induce one to enter. Appearances, however, are proverbially deceitful, and happening to enter the little church of S. Maria delle Grazie we found ourselves in a building which on a smaller scale equals the duomo in design as it does in antiquity. (..) The capitals are Byzantine, some like that I saw in the cathedral and one covered with a network of interlacing foliage like those at S. Vitale in Ravenna. (..) Some of the capitals in this church have the Byzantine impost block or second capital on the top of the first, which is generally characteristic of the style (see those at S. Giovanni Evangelista at Ravenna). T. G. Jackson

It is a beautiful little Byzantine church six bays long, with many fragments of mosaic pavements in the same style as those at the duomo, and like them abounding in inscriptions. T. G. Jackson A recurring decorative motif in this mosaic (in addition to Solomon's knots) is made up of four peltas, the shield of the Amazons. It was widely used across the Roman Empire for the decoration of buildings, including early churches as at Kourion, a port on Cyprus, or at Thysdrus in Tunisia (the latter link opens in another window).

A third large church was built in the VIth century on a previous one, similar to S. Maria delle Grazie and the Cathedral. It was situated outside the walls and because some sarcophagi were found in the excavated area, archaeologists believe it was a funerary church similar to that found at Salona. Its floor was decorated with mosaics which have retained their brilliant colours, better than those inside the other two churches.

Patriarch Domenico Marengo in 1045 desired to quit Grado on account of its miserable condition; the next Patriarch Cervoni was reduced to such straits that Gregory VII wrote to beg the doge of Venice to supply his needs; and the succeeding patriarchs, Giovanni Gradenigo (1105-1131) and Enrico Dandolo (1131-1186), actually moved their residence to Venice. Henceforward the patriarch was a stranger to his titular city; he had a palace at Venice, and took precedence as the first citizen of the Republic; his authority was recognised over all the islands of the Lagunes. (..) In the year 1450 the seat of the patriarchate was formally transferred from Grado to Venice, where it has survived to the present day. T. G. Jackson The imposing bell tower was built in the XVth century and a rotating hollow copper statue of St. Michael was placed at its top. The current statue was made in 1875 and it is twice the size of the original one. A similar rotating statue can be seen at S. Giorgio Maggiore in Venice, at Rovigno and at other towns which were subject to Venice. Move to: Introductory page Roman Aquileia - Main Monuments Roman Aquileia - Tombs and Mosaics Early Christian Aquileia Medieval Aquileia Chioggia: Living on the Lagoon Chioggia: Churches Chioggia: Other Monuments Roman and Medieval Cividale del Friuli Venetian Cividale del Friuli Palmanova Roman and Byzantine Parenzo (Porec) Medieval and Venetian Parenzo (Porec) Roman Pola (Pula) Medieval and Venetian Pola (Pula): Churches Medieval and Venetian Pola (Pula): Other Monuments Pomposa Roman Ravenna Ostrogothic Ravenna Byzantine Ravenna: S. Apollinare in Classe Byzantine Ravenna: S. Vitale Byzantine Ravenna: Other Monuments Medieval Ravenna Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Walls and Gates Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Churches Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Other Monuments Rovigno (Rovinj) Roman and Medieval Trieste Modern Trieste     |