What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in August 2014. |

- Introduction - Introduction(a sphinx at Diocletian's Mausoleum) The Romans conquered northern Italy and set foot in today's Albania during the Macedonian Wars (215 BC - 148 BC). As a result of these conquests they controlled all the western shores of the Adriatic Sea and its connection to the Ionian Sea.

The eastern shores of the Adriatic Sea were inhabited by the Liburni to the north and by the Delmatae to the south. The former were very skilled seamen and are believed to have reached the region by sea, perhaps from the Aegean coast of today's Turkey. The latter were herdsmen and lived in the mountains by the coast. The Liburni developed a long and narrow ship which they used for raids along the Italian shores or for attacking merchant ships. The Romans launched some campaigns aimed at subduing the Liburni and eventually acquired control over the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea. The tribes living in the mountains were not much affected by these campaigns as they were only asked to recognize the formal sovereignty of Rome over their territories. At the time of Emperors Augustus and Tiberius a series of rebellions by the Delmatae were quelled by the Romans. They founded a series of colonies to strengthen their control over a territory which eventually spanned from the Adriatic Sea to the River Danube. Salona, an excellent port, opposite that of Ancona on the Italian coast, became the capital of the Roman Province of Dalmatia.

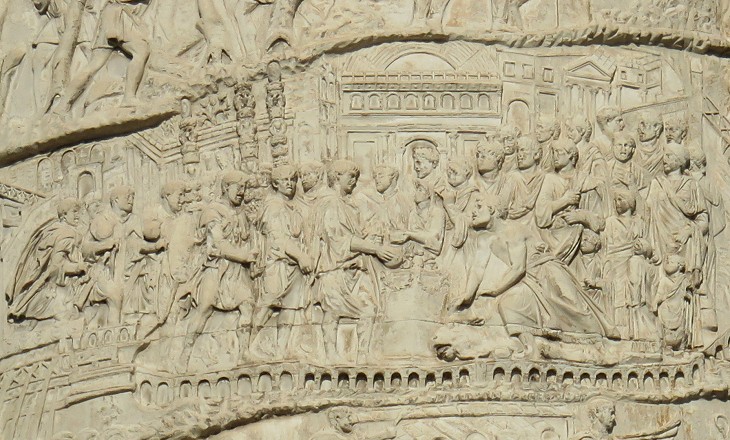

Salona was a flourishing town when Emperor Trajan landed there in 105 AD. It was known for its very long wharf and it had a large theatre and many temples which were sketchily depicted on the column erected in Rome to celebrate the Dacian campaigns. In 295 Emperor Diocletian, who was born near Salona, decided to build there a fortified palace by the sea, three miles from the town. Ten years later he abdicated and retired to Salona where he lived until his death in 311. His palace eventually became a small town of its own (Spalato). In the VIIth century many inhabitants of Salona sought refuge within its walls, because their large town had been sacked by Slavs and Avars.

The ruins of Diocletian's palace at Spalato are the main remaining evidence of the ancient prosperity of Dalmatia. The archaeological site of Salona includes only a part of the town and there is no remaining evidence of the harbour, yet the sheer size of the excavated area is impressive. Other ancient works of art or architectural elements can be found at Trał which is located at the opposite end of the bay of Salona. However, as a general comment, it is fair to say that the number of remaining sculptures and other works of art of the Roman period is by far lower than that one would expect to find in a region which had been so prosperous.

Spalato did not have a large harbour such as Salona had, but when the European economy recovered after the year 1000, it became a port of call along the maritime trade route between Venice and Constantinople. A relatively prosperous medieval town developed in the ruins of Diocletian's palace. Its inhabitants turned the emperor's mausoleum into a cathedral they started to embellish (the town had "inherited" the bishopric see of Salona). The Republic of Venice was given by the Byzantine Emperors a sort of protectorate over the Adriatic Sea. Doge Pietro Orseolo II (991-1009) acquired the title of Dux Dalmatiae. The Venetian government imposed trade restrictions on the small maritime towns of Dalmatia. Some of them sought the protection of the Kings of Hungary, but in 1409 Venice bought Spalato, Trał, Sebenico and other ports from King Ladislaus of Naples, a pretender to the Hungarian throne, and retained control over them until 1797.

In the XVth century Venice was the largest maritime power and based its wealth on trade. The Republic was only interested in having a series of ports along the Dalmatian coast and did not care much about what was happening beyond the high mountains which run along it. In 1526, the Venetian ambassador at Buda, the capital of Hungary, congratulated Sultan Suleyman for his victory at Mohacs, which put an end to the Kingdom of Hungary. He did not understand that by that victory the Ottomans would have strengthened their control over the region and eventually attempted conquering the Venetian possessions in Dalmatia.

In 1537 the Ottomans seized the fortress of Clissa which was defended by a local warlord. By this conquest they were just a few miles from Spalato, yet for more than a century they did not launch an all-out assault on the town. It was only during the War of Candia (1645-69) that Ottomans and Venetians fought a veritable war in Dalmatia. The Ottomans failed to seize Spalato and eventually they lost Clissa. The fortress had such a strategic importance that they even offered to lift the siege to Candia in return for it. In the 1669 peace which put an end to the war, Clissa remained in Venetian hands. It was strengthened and it became the starting point of campaigns which led to the conquest of a large inland region. The border between Venetian and Ottoman territories which was established by the 1718 Peace of Passarowitz is today part of the border between the Republic of Croatia and that of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The Republic of Venice came to an end in 1797. During the four centuries of Venetian rule the towns of Dalmatia, notwithstanding a heavy fiscal burden and limits to their trade, flourished and local authorities and noble families embellished them with monuments. In general the buildings were designed according to Venetian Gothic patterns (i.e. that blend of Gothic and Byzantine features which characterized many Venetian palaces). Artists from Florence and other Italian towns travelled to Dalmatia and added a Renaissance touch to some of its monuments. The development of local skilled sculptors was helped by the availability of a white limestone which could be easily worked. A sculptor and architect, born at Zara, in the northern part of Dalmatia, stands out for his many works of art. He signed himself (in Latin) as Georgius Dalmaticus and Georgius Sibenicensis, but he was usually known as Giorgio Orsini until the beginning of the XXth century. He started his career in Venice where he married and returned several times. The design and decoration of the Cathedral of Sebenico is regarded as his masterpiece. He spent his last years at Ancona where he designed three large portals. Giovanni Dalmata from Trał is another famous sculptor of this region. He mainly worked for (Venetian) Pope Paul II (you may wish to see the portal he designed at Vicovaro).

The access to the bodies governing the Republic of Venice was restricted to members of noble families listed in Il Libro d'Oro (The Golden Book). The wealthiest families of the territories ruled by Venice did not have access to Il Libro d'Oro, but could be members of the Nobili Consigli (Councils of Noblemen) who assisted the Venetian representatives in dealing with local matters. The Cippico, who claimed to descend from an ancient Roman family, were listed among the noblemen of Trał in 1315. A member of the family was appointed Senator of the Kingdom of Italy in 1923.

The XXth century has been a saeculum horribilis for Dalmatia and even more for other regions of the Balkans. The disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires in 1918 led to the creation of a series of nations which were economically weak and internally divided along religious, language and ethnic lines. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia both failed in keeping together the "Slavs of the South" (the meaning of Yugoslavia). "Ethnic cleansing" sounds like a program for washing machines but it is not. During the wars which followed the collapse of Yugoslavia in 1991 it was used to conceal the fact that the aim of the various parties involved in the conflict was to literally massacre their enemies. "Attempted genocide" more effectively depicts what happened. In 1993 the United Nations established the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia to prosecute the persons responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law. I remember visiting Dalmatia in 1985. References to Marshal Josip Broz Tito, the leader of Yugoslavia between 1945 and 1980, were everywhere (streets, statues, names of schools and barracks, etc). They are all gone, replaced by those to a new "Father of the Nation". The image used as background for this page shows a sphinx drawn by Robert Adam (1728-92), a Scottish architect and engraver who published Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia in 1764. Note on names: similar to what is done in this website for other locations having a double name (e.g. Constantinople/Istanbul, Edessa/Sanliurfa and Philippopolis/Shahba) the current Croatian name is used when referring to monuments built after 1918 and the historical name when referring to those built before that year. Move to: Spalato - Ancient Walls Spalato - Ancient Town Spalato - Mausoleum Spalato - Venetian fortifications Spalato - Cathedral Spalato - Churches Spalato - Other Buildings Salona Clissa Trał - the Town Trał - Cathedral Trał - Churches Sebenico - the Town Sebenico - Cathedral Sebenico - Churches and Palaces     |