What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in September 2014. |

- Clissa - Clissa(a sphinx at Diocletian's Mausoleum) You may wish to read an introduction to this section first.

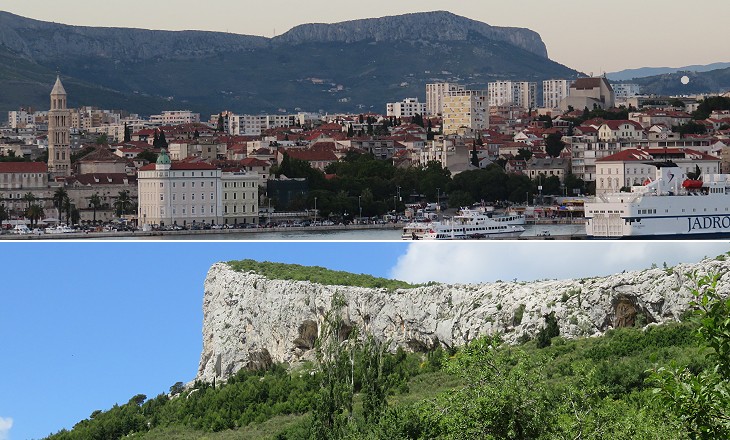

As the steamer rounds the long island of Bua the traveller will look eagerly for the first view of Diocletian's home. While the town is still hidden by the island it can be seen that the natural beauties of the situation are considerable. The higher mountains once more approach the shore, and straight in front rises the grand mass of Monte Mossor, bare and craggy. Sir Thomas Graham Jackson (1835-1924), one of the leading architects of his time - Dalmatia, the Quarnero and Istria - 1887

The mountains had a threatening aspect for the XVI-XVIIth century inhabitants of Spalato, because they were occupied by the Ottomans who could almost watch what was going on at the harbour of Spalato from their fortress at Clissa. When in 1420 the Venetians bought a string of ports along the coast of Dalmatia, they had no interest whatsoever in the inner parts of the country, which were conquered by the Ottomans in the early XVIth century. In 1538 and 1571 the Ottomans launched attacks on Spalato, but were unable to conquer the town.

Clissa controlled the road which led from the coast to today's Bosnia-Herzegovina, one of the nations into which the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia split in 1992. Clissa was the capital of a small sanjak (province) of the eyalet of Bosnia, a major division of the Ottoman Empire until 1908 when it was annexed by the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

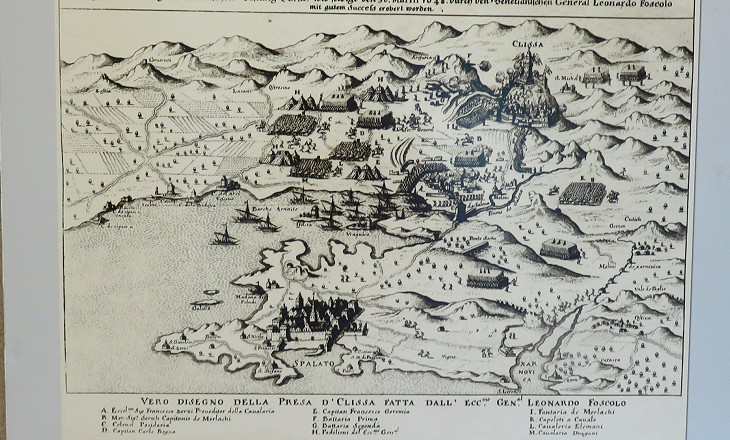

The fortress was situated on a veritable eagle's nest as it was protected by a deep ravine which surrounded it on all sides. The Ottomans believed it was impregnable and yet its defenders surrendered it to the Venetians in 1648, during the War of Candia. It was a major strategic loss for the Ottomans who repeatedly tried to recover the fortress during peace negotiations, but the Venetians held on to their new possession even though they ceded Candia in 1669.

E con questa occasione vennero alla pubblica divozione le feroci popolazioni de' Morlacchi, che sì per la pratica de' siti, come pel natural odio contra Turchi, difesero poi con valore e sè stessi e il paese. (And on this occasion the savage Morlach tribes accepted the Venetian rule. Their knowledge of the mountains and their hate of the Turks made them valiantly fight to defend themselves and the country). Compendio dell'Antica e Moderna Istoria della Repubblica di Venezia - Venice 1754. The Venetians employed mercenary troops and for the attack on Salona they hired Morlachs, shepherds who lived on the mountains of Dalmatia.

The Ottoman mosque was turned into a small church and its adjoining minaret was torn down. In the bare interior some fragments of the Venetian decoration can still be found. One of them clearly refers to the military nature of the site.

The eastern side of the fortress appears to have been modified after 1648 in order to place more cannon there. Clissa however lost much of its military importance after the Venetians seized some inland towns (e.g. Sinj, Knin and Imotsky) during the wars which ended in 1699 and 1718. By these conquests the territory of Dalmatia greatly increased and its population was no longer made up of only the urban communities along the coast who had a long tradition of economic and cultural links with Venice, but also included Slav peasants and shepherds who spoke Serbo-Croatian. In the XIXth century when nationalism became rampant in Europe, all components of the population of Dalmatia stressed their ethnic/religious origin and identified themselves with the Italian, Croatian or Serbian nations. Almost all of the "Italophiles" left Dalmatia by 1945 as a consequence of WWII. The "Serbophiles" did so in 1995 after their attempt to establish an independent republic failed.

Clissa continued to be used as a fortress/prison until WWII. It is now open to the public and it houses a small museum with copies of some interesting etchings. Sadly all Venetian inscriptions and coats of arms have been removed or erased. Move to: Introductory page Spalato - Ancient Walls Spalato - Ancient Town Spalato - Mausoleum Spalato - Venetian fortifications Spalato - Cathedral Spalato - Churches Spalato - Other Buildings Salona Traù - the Town Traù - Cathedral Traù - Churches Sebenico - the Town Sebenico - Cathedral Sebenico - Churches and Palaces

|