What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in August 2014. |

- Spalato - Ancient Town - Spalato - Ancient Town(a sphinx at Diocletian's Mausoleum) You may wish to read an introduction to this section first.

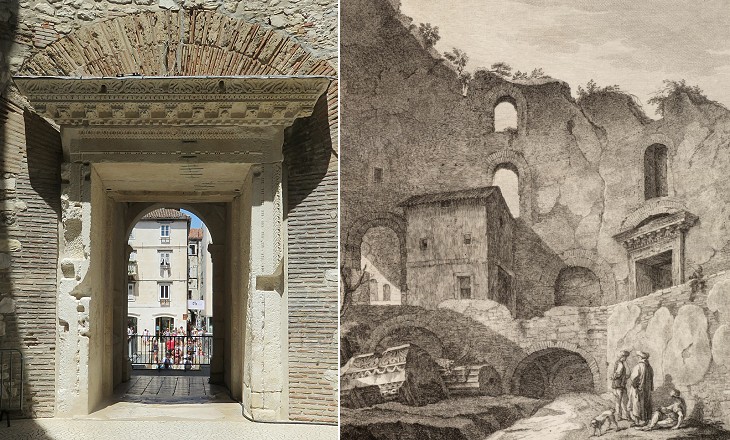

Maybe the groups of people Robert Adam portrayed in his etching were not actually there when he visited Spalato in July 1757 and were added to make the view more picturesque. The heart of the palace is a small peristyle (a colonnaded courtyard) at the end of a now lost street which began at Porta Aurea. The entrance to the emperor's apartments was preceded by a sort of triumphal arch known as Serliana (three smaller Serliana decorated the waterfront side of the palace). Two temples were accessed through the long sides of the Peristyle: to the left a large octagonal building which is believed to have been the emperor's mausoleum (see a page on it) and to the right a small traditional temple that is covered in this page.

Adam's task of providing his readers with an enthralling view of the Peristyle would have been much more difficult today as he would have found himself in a shopping mall. The steps are leased to Café Luxor (you might wish to see their website to understand what goes on there day and night - it opens in another window); the central part of the square is occupied by a platform for shows; an opening below the Serliana leads to a bric-a-brac bazaar housed in the underground structures of the palace.

What exactly Diocletian had in mind when he ordered the construction of the palace is difficult to understand. The complex is definitely too small to be a place from which an emperor could rule the Empire and actually Diocletian set his residence at Nicomedia, today's Iznit near Nicea and Byzantium. If instead he wanted a location where to rest and enjoy life then the complex is more similar to a barracks than to Villa Adriana, the finest remaining example of an imperial villa.

Those who built and decorated the palace could avail themselves of a white limestone quarried on Brac, an island opposite Spalato. In order to obtain some contrast effects reddish granite columns were brought from Egypt and greenish marmor carystium or cipollino columns from Karistos, on the Greek island of Euboea. Considering the height of the columns, the space between them is narrower than that which can be seen in previous Roman monuments (e.g. Arch of Septimius Severus at Leptis Magna).

The access to the imperial apartments from the Peristyle occurred through a domed vestibule. The floor of the vestibule had collapsed when Adam visited Spalato and he could show the underground passages beneath it. He added some broken lintels and columns of a gigantic size, similar to what Giovanni Battista Piranesi used to do in his etchings of ancient Rome which greatly influenced Adam (you may wish to see an etching by Piranesi - it opens in another window). The image used as background for this page shows the reconstruction of the vestibule by Adam.

Adam was assisted by Charles-Louis Clérissau, a French painter living in Rome, and by two Italian draughtsmen. The team was very diligent in recording all the details of the decoration, even though in some instances it was a pretty academic one which combined together traditional patterns. Adam eventually made use of these drawings in the decoration of houses and furniture in England and Scotland. Clérisseau added Diocletian's palace to his vast repertory of Roman ruins which he painted for Grand Tour travellers (you may wish to see his "Vestibule Revisited" - the title is mine - it opens in another window)

Diocletian abdicated in 305 and retired to Spalato. While he walked along the colonnaded loggia on the waterfront or sat there watching the sun set over the sea, the "underground city" which lay beneath the imperial apartments was bursting with activities. Similar structures had already been developed in the design of Domus Tiberiana on the Palatine in the early Ist century AD. Today part of these underground structures have been turned into a bazaar (you may wish to see what they sell - it opens in another window).

The underground structures included baths and some halls the use of which is yet to be clearly understood. Because of their size and aspect they might have been part of the imperial apartments. Although the palace was supplied water by an aqueduct, nymphaea, large monumental fountains, have not been found.

Adam believed this temple to be dedicated to Aesculapius, based on Illyricum* Sacrum, a book written by Daniele Farlato, a Jesuit, and published in Venice in 1751. Today it is known as the Temple to Jupiter. It eventually became a baptistery, but, as the etching shows, it was not modified in order to give it a more Christian appearance. * Illyricum was the name given by the Romans to a region which roughly corresponded to the former Yugoslavia and included Dalmatia.

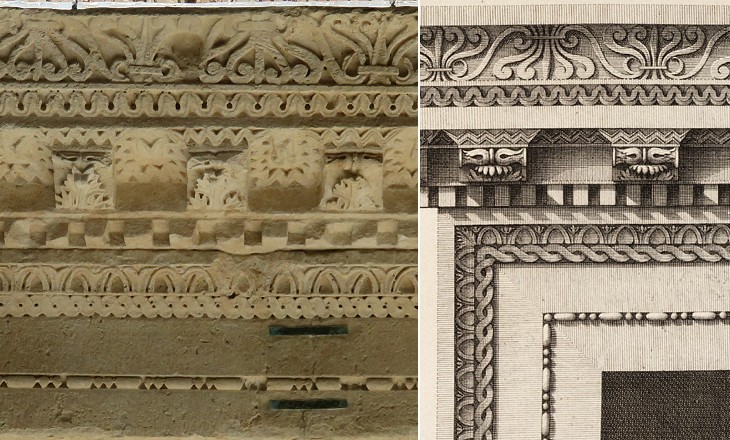

The decoration of the portal is indicative of the changes in art which began to occur at the time of Diocletian and became more evident during that of Emperor Constantine. Putti working in a vineyard and the depiction of birds are motifs which can be found in many buildings of the Late Empire and in particular at S. Costanza in Rome. The use of drill in reliefs is another change worth mentioning.

The sarcophagus shown by Adam is now in the Archaeological Museum of Split. The sphinx which is now at its place is one of some thirty small sphinxes that were brought from Egypt to embellish the palace. Some were made of basalt, a hard black stone, and others of granite, another hard stone thus named after its "grains". Notwithstanding the sphinxes, there are no other references to Egypt, such as lotus leaf capitals (see those at Persepolis) or obelisks, in the design of the palace.

Some details on the lintel recall the efforts made by Diocletian to reform and strengthen the Empire after the long period of crisis which preceded his rise to power. Weak emperors had been unable to effectively deal with the growing threat of the Sassanids on the eastern border of the Empire. A revolt led by Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra attempted to establish a separate empire including the whole of Syria and Egypt. These threats were eventually staved off, but Diocletian felt the Empire would have gained if its rulers had been regarded as having a divine origin or investiture, as the Sassanid kings had. He assumed the title of Iovio (of Jupiter) for himself and imposed that of Herculio (of Hercules) to Maximian, the general he associated to power. The lintel shows the heads of Jupiter/Diocletian and Hercules/Maximian at the sides of the eagle symbolizing the Empire. Sol Invictus (Unconquered Sun), a personification of the Sun which was worshipped in the army, is most likely portrayed to the left of Jupiter/Diocletian.

The inhabitants of Spalatro have destroyed some parts of the palace, in order to procure materials for building. In other places houses are built upon the old foundations, and modern works are so intermingled with the ancient, as to be scarcely distinguishable. Adam described the difficulties he encountered in his task by these words. Yet he was luckier than a today's visitor because he did not have to face the hostility of waiters and shopkeepers who despise those who do not eat, drink or buy and are only interested in ancient stones.

The imperial apartments occupied the southern half of the palace almost entirely. In the northern half the lack of ancient walls in two square areas suggests they were the kitchen gardens where the emperor grew his "famous" cabbages. Diocletian actually relinquished the imperial fasces (power) of his own accord at Nicomedia and grew old on his private estates. It was he who, when solicited by Herculius (Maximian) and Galerius for the purpose of resuming control, responded in this way, as though avoiding some kind of plague: "If you could see at Salonae the cabbages raised by our hands, you surely would never judge that a temptation." Sextus Aurelius Victor - Epitome De Caesaribus - Translated by Thomas M. Banchich. Introductory page Spalato - Ancient Walls Spalato - Mausoleum Spalato - Venetian fortifications Spalato - Cathedral Spalato - Churches Spalato - Other Buildings Salona Clissa Traù - the Town Traù - Cathedral Traù - Churches Sebenico - the Town Sebenico - Cathedral Sebenico - Churches and Palaces     |