What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in October 2007. |

- part three: a Cosmopolitan City - part three: a Cosmopolitan City(mosaic showing the body of St. Mark being carried to the church dedicated to him in Venice) For centuries Venice was a very cosmopolitan city, a bridge between western Europe and the Levant.

The members of the various foreign communities tended to live in the same neighbourhood near their national church or their warehouses. These were aligned along the Canal Grande: some sections of this waterway are still named after the trade which took place there (Riva del Carbon - coal dock; Riva del Ferro - iron dock).

Many Venetian merchants lived in Constantinople; notwithstanding the seven wars fought between Venice and the Ottomans, commercial ties were never entirely severed. Venice granted reciprocal rights to Ottoman merchants. They were mainly interested in buying luxury goods manufactured in Venice. In 1535 Sultan Suleyman commissioned the Venetian goldsmiths a headdress similar to the papal triregno, but with four crowns, rather than three; the four crowns were meant to indicate that the Sultan was the lord of both the East and the West, both in land and at sea. The crown was shown to the Doge and to the other magistrates of the Republic before being shipped to Constantinople, so we have descriptions of its stones and an engraving showing it (you can see it in this external link). In 1621 Turkish merchants were assigned a large building on the Canal Grande; in addition to warehouses it housed a Turkish hammam and a mosque, probably the only one in western Europe. Fondaco dei Turchi was rebuilt "as it was" in the XIXth century.

The Venetians portrayed as Turks all the Easterners, including Anianus, the first convert St. Mark won to Christianity in Alexandria (the image in the background of this page shows a relief in Scuola Grande di S. Marco where Anianus is portrayed as a Turk). A mosaic in St. Mark's was meant to show the XIth century Arab custom officers who did not prevent the smuggling of St. Mark's body; they were portrayed as XVIIth century Turks. According to the tradition the Venetians placed the corpse in a large basket covered with herbs and swine's flesh which the Muslims hold in horror. The bearers cried kwhazir (pork) while going towards their ship: the Arab custom officers in charge of clearing the vessel refused to inspect the basket and thus the relic was brought to Venice.

The Greek community lived near a church dedicated to St. George: it was built in the XVIth century and it is the only Renaissance style Orthodox church. It was decorated by painters from Candia (Crete) and the nearby Collegio Greco houses a collection of icons. The church was (and still is) directly subject to the Orthodox Patriarch of Constantinople. The Greeks of Venice were seamen, merchants and soldiers: some had followed the Venetians when their towns fell to the Ottomans. Venice had a very developed printing industry which provided the whole of Greece with books which helped retain the national culture.

Mori in most parts of Italy is a reference to the Moors, the Arabs of western North Africa. In Venice however Mori meant the inhabitants of Morea, the Greek peninsula which is today best known as Peloponnese. In the XIIth century three wealthy merchants from Morea built a palace near Madonna dell'Orto: they placed on the building and in the surrounding area reliefs and statues showing their trade and themselves (all wearing a turban).

Venice extended its influence and in part its direct rule on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea: the Slavic people who lived inland were called Oltramarini (beyond the sea). The term Schiavoni designated those who lived on the central and northern sections of the coastal strip which today belongs to Croatia and Montenegro. The Schiavoni were regarded as valiant and faithful soldiers: they proudly fought at the defence of Candia and later on at that of Corfu. It goes without saying that they were greatly devoted to St. George, the warrior saint, and dedicated their church in Venice to him.

In 1489 Venice was bequeathed Cyprus by Caterina Cornaro, widow of King James II of Lusignan. She is buried in a grand monument in the Venetian church of S. Salvatore. The kings of Cyprus were often caught in the fight between Venice and Genoa. In 1362 King Peter I personally visited both cities in order to establish good relations with them. In Venice he received a warm welcome and was hosted in a palace on the Canal Grande: in return the king allowed his coat of arms to be placed on the fašade of the palace. The coat of arms shows the cross of the Holy Sepulchre (a large cross surrounded by four small ones), because he claimed to be the King of Jerusalem.

Venice had some outposts on the coast of Albania: these were attacked by Sultan Mehmet II who in 1474 laid siege to Scutari (Shkoder), the main town of northern Albania; the inhabitants remained faithful to Venice and managed to repel the Ottoman assaults. In 1478 however Venice surrendered Scutari to the Turks in the frame of a peace agreement which put an end to the first war with the Ottomans. The defence of Scutari became a symbol of the Albanian heroism. This explains why the fašade of Scuola degli Albanesi (their community centre in Venice) is almost entirely covered by a relief celebrating that event. Venice retained for a long period an outpost in Albania at Butrint.

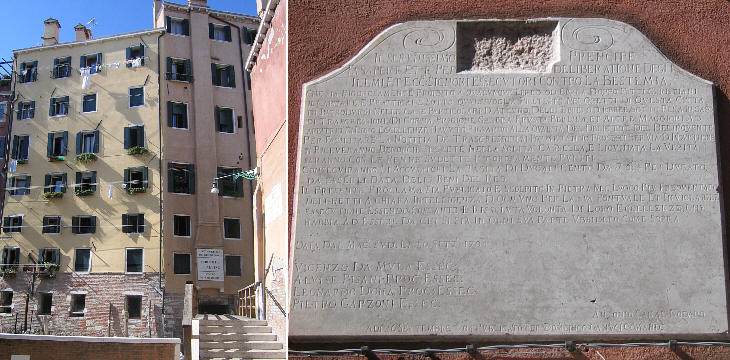

At the beginning the Jews of Venice lived on a group of islets at a certain distance from the rest of the city: the area is still named la Giudecca after them: they were later on forced to move to mainland Mestre and eventually in 1516 they were confined to a small section of Cannaregio, one of the six districts into which Venice was (and still is) divided. In the chosen area there were some foundries so it was known as ghetto, a phase of iron manufacturing. The bridges leading to the ghetto were closed at night: outside the ghetto, the Jews had to wear a yellow bonnet, but some of the highly praised Jewish doctors were exempted from wearing it. The ghetto was enlarged in 1541 and again in 1633, yet the area was so densely populated that some buildings had more than six storeys. Overall the Republic of Venice was more tolerant towards the Jews than other Italian states and tried to minimize the situations which could lead to outburst of violence against them. With this aim in 1704 a law forbade converted Jews to set foot in the ghetto: the aim of the provision was to avoid the kidnapping of infant Jews to christen them, a practice which was frequent in the Papal State.

The Armenians (together with the Greek Orthodox and the Jews) were recognized as an approved millet (confessional community) by the Sultan and in general until the rise of nationalism in the XIXth century Armenian communities in the Ottoman Empire were rather prosperous. In 1717 however the Turks closed an Armenian monastery in Modon. They had just reconquered that fortress after 30 years of Venetian rule and they regarded Peter of Manug Mekhitar, the founder of the monastery, as an enemy because he preached the religious unity of his people in the frame of the Roman Catholic Church. The Venetian Senate assigned a small island to the Armenian monks. In the past it had been used as a leprosarium and for this reason was dedicated to S. Lazzaro (Lazarus).

The monastery became a centre for preserving and spreading Armenian culture and is still the mother-house of the Mekhitarist Order. See these other pages: Venice and the Levant - Part one - The Early Days Venice and the Levant - Part two - A Powerful Player Venice and the Levant - Part four - A Military Power Venetian Fortresses in Greece

|