What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in December 2014. |

- Introduction - Introduction(Longobard weapons at Museo Archeologico di Cividale) In the heat of the battle, a violent tempest, such as is often felt among the Alps, suddenly arose from the East. The army of Theodosius was sheltered by their position from the impetuosity of the wind, which blew a cloud of dust in the faces of the enemy, disordered their ranks, wrested their weapons from their hands, and diverted, or repelled, their ineffectual javelins. This accidental advantage was skilfully improved, the violence of the storm was magnified by the superstitious terrors of the Gauls; and they yielded without shame to the invisible powers of heaven, who seemed to militate on the side of the pious emperor. Edward Gibbon - The History of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire - Volume 3 - 1782

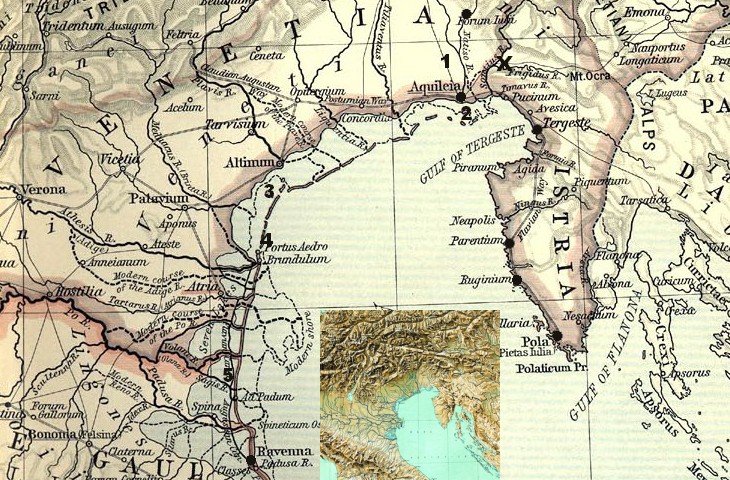

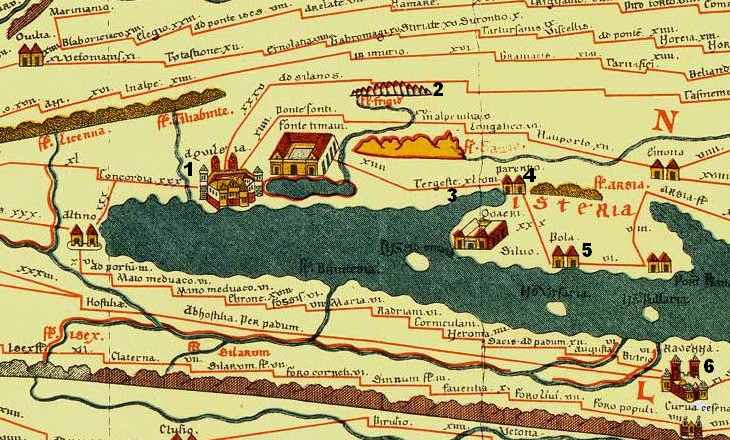

The battle described by Gibbon occurred in September 394 AD near the River Frigidus (Cold), which at that time was most likely a tributary of the Natiso (aka Akilis), the river of Aquileia, one of the largest cities of the Roman Empire. The battle had a special importance because of two aspects: a) Theodosius was leading a Christian army, his opponents Eugenius and Arbogastes and their mainly Gaulish troops were sympathetic towards the traditional beliefs. The wind was decisive in the outcome of the battle and it was therefore interpreted as a sign of divine intervention by Christian writers such as St. Augustine, similar to that which had occurred at the Battle of Ponte Milvio. b) the army of Theodosius was partly composed of Goths. They had been allowed to cross the River Danube into the Roman province of Moesia (today's Bulgaria) by Emperor Valens in ca 370, but in 378 they rebelled and defeated and killed the Emperor at Adrianopolis. In the following years the Goths and other "barbarian" tribes settled south of the Danube in a permanent way. Theodosius decided to enrol Alaric, leader of Gothic cavalrymen, in the army he was preparing to march against Eugenius and Arbogastes. At the battle of the River Frigidus Alaric led the first attacks and he earned there a fame of brave military leader. In the following year he was acclaimed king of the Visigoths, a term meaning Western Goths which was used in the VIth century to distinguish them from the Ostrogoths, Eastern Goths, who crossed into Roman Empire territories a century later.

In 401 Alaric and his Goths crossed the Alps and reached the northern Italian plain through the River Frigidus valley. It was the first of a series of invasions which ended in 568 with that of the Longobards. When Alaric first entered north-eastern Italy this region had a number of sizeable towns, in addition to Aquileia. They were a magnet which attracted him and the invaders who came after. They did not look at the towns as locations where to settle, because their tradition was a nomadic one, but only as a source of loot. In 452 Attila, leader of the Huns, ravaged northern Italy and set fire to Aquileia. According to tradition his soldiers built a mound twenty miles away for him to watch the city burn.

In the early Vth century the towns of north-eastern Italy retained some of the buildings (fora, amphitheatres, circuses, baths, etc) which were typical of the Roman way of living in the first two centuries AD. The Early Middle Ages (from the Vth to the Xth century) were characterized by a marked decline of the urban population and many towns were abandoned while in others the number of inhabitants shrank dramatically. In the VIIIth century the entire population of Rome probably did not exceed the audience of the amphitheatre of Pola, a relatively small Roman town.

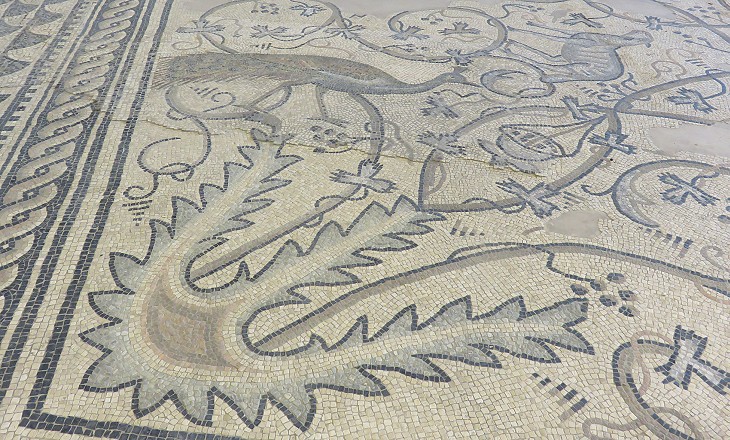

In 380 Christianity (in its Nicene Creed) was declared the sole legitimate religion of the Empire, but already prior to this decree many large Christian communities built churches in the main towns of north-eastern Italy and especially at Aquileia. This city was an important port on the River Natiso and it had many links with the eastern parts of the Empire and in particular with Alexandria where a large Christian community first developed. Valerian, Bishop of Aquileia in ca 369-388, was an outspoken supporter of the Nicene Creed.

In 402, immediately after the first invasion by Alaric, Emperor Honorius decided to move his residence from Milan to Ravenna, because the latter was surrounded by swamps and marshes which made it more easily defensible. In addition Classe, its seaport, allowed easy links to Constantinople. Ravenna became the capital of the first two Kingdoms of Italy established by Odoacer (476-93) and Theodoric (493-540). Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit (Captive Greece captured her rude conqueror) is a sentence by Horace which could be applied to Italy and its first Gothic conquerors. Theodoric availed himself of advisers from the ancient Establishment. Latin remained the official language and was eventually spoken by the invaders too. Only a very limited number of Italian words have a Gothic root.

The attempt by Emperor Justinian to reconquer Italy initially succeeded and Ravenna continued to flourish with new churches being built and lavishly decorated. Their design and mosaics no doubt reflected the prevailing trends in Constantinople and marbles came from quarries near that city. As a matter of fact because VIth century mosaics at Constantinople, including those at Hagia Sophia, were all destroyed by the iconoclasts, those of Ravenna are the only ones which depict the splendour of the Byzantine court and include contemporary portraits of the emperor and his wife.

Ravenna was not the only town to be embellished with large churches during the reign of Emperor Justinian. Bishops acquired great power in the late IVth century and afterwards; the ecclesiastical career (which did not forbid marriage) replaced the ancient cursus honorum (a succession of public offices) as a way to achieve a high position in society. Donations to churches became very frequent as a mean to acquire merits for the afterlife. While in Rome churches were built using columns and capitals taken from ancient monuments, those shown above were made in Constantinople and then shipped to Parenzo.

In 568 the Longobards invaded Italy. They were unopposed by the Byzantines, but they did not have strength enough to conquer the whole country and Rome and Ravenna, its two main cities. The Byzantine navy was able to retain a series of ports on both sides of the Adriatic Sea (e.g. Ancona). Although a formal border was never established the land by the sea belonged to the Byzantines. Many inhabitants of the impoverished or destroyed inland towns sought refuge on small coastal or lagoon islands. Venice is the best known example of a city which was founded by refugees, but it is not the only one and this section covers Chioggia (Venice's little sister) and Grado, the original see of the Patriarch of Venice.

The Longobards had a king who usually resided at Pavia, near Milan, but they established a powerful duchy at Forum Iuli (today's Cividale) which eventually gave its name (shortened in Friuli) to the easternmost part of Italy. The Dukes of Forum Iuli were generally able to prevent other invaders such as Avars and Slavs from entering Italy and the town retains some monuments and works of art of that period. In 775 the Duchy was conquered by Charlemagne who strengthened its military importance.

During the XIth century some religious institutions acquired great wealth and power. The Patriarchate of Aquileia ruled many territories in today's Italy, Austria, Slovenia and Croatia. Patriarchs did not hesitate to personally wage war to expand their possessions. The Abbey of Pomposa flourished in the XIth century thanks to large number of donations, including major salt ponds north of Ravenna. The use of mosaics characterized the decoration of churches in this part of Italy during the Early Middle Ages. Frescoes, which were the usual form of painting of the ancient Romans, were again utilized from the XIIth century onwards. In some locations such as Venice and Chioggia frescoes were often damaged by humidity and, when the use of oil painting began to be introduced, Venetian artists were the first to paint teleri, large canvases.

Most of the territories of the Patriarchate of Aquileia were eventually acquired by the Republic of Venice and by the Habsburg Archdukes of Austria. While the towns on the coast of Istria were Venetian, in 1382 Trieste called for the protection of the Archdukes of Austria, who acquired the title of Holy Roman Emperor in 1452. In 1511 Emperor Maximilian I conquered Gradisca, a Venetian fortress near the River Frigidus which played a key role in the defence system of the Republic. On 7 October 1593, the anniversary of the Battle of Lepanto, the Venetians laid the first stone of Palmanova, a new fortified town near Aquileia. The choice of the foundation day was meant to indicate that the purpose of Palmanova was to stop an Ottoman invasion, but the real objective was to protect Venice in case of Austrian attack. The design of Palmanova was based on state-of-the-art military architecture and at the same time it represented a major attempt to actually build the Ideal City many Renaissance artists and philosophers dreamt of. In the year 1600 the towns covered in this section were part of three different countries: Archduchy of Austria (Trieste, Grado and Aquileia), Republic of Venice (Cividale, Palmanova, Parenzo, Rovigno, Pola and Chioggia) and Papal State (Pomposa and Ravenna). Today they are all in the Republic of Italy except Parenzo, Rovigno and Pola which are in the Republic of Croatia.

The focus of this section is on the Early Middle Ages, but it includes monuments built previously or later (until the end of the XVIIIth century). The image used as background for this page shows a relief portraying Jupiter Ammon in the Forum of Aquileia. Move to: Roman Aquileia - Main Monuments Roman Aquileia - Tombs and Mosaics Early Christian Aquileia Medieval Aquileia Chioggia: Living on the Lagoon Chioggia: Churches Chioggia: Other Monuments Roman and Medieval Cividale del Friuli Venetian Cividale del Friuli Grado Palmanova Roman and Byzantine Parenzo (Porec) Medieval and Venetian Parenzo (Porec) Roman Pola (Pula) Medieval and Venetian Pola (Pula): Churches Medieval and Venetian Pola (Pula): Other Monuments Pomposa Roman Ravenna Ostrogothic Ravenna Byzantine Ravenna: S. Apollinare in Classe Byzantine Ravenna: S. Vitale Byzantine Ravenna: Other Monuments Medieval Ravenna Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Walls and Gates Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Churches Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Other Monuments Rovigno (Rovinj) Roman and Medieval Trieste Modern Trieste     |