What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in December 2008. |

- Hattusa - page one - Hattusa - page one(Ali Pacha Hammam in Tokat) Little is known about the origins of the Hittites. Their language belongs to the Indo-European family and it is assumed that they immigrated into Central Anatolia via the Caucasus sometime during the second half of the 3rd millennium BC. The Hittites used the name Hatti as the designation for their land. Hattusa is first mentioned by King Anitta who called himself "one from Hattusa". The choice of the site to found the town was due to the presence of rocks which could be easily fortified and of a small river which provided a precious water supply in an arid region.

The Hittites made extensive use of cuneiform writing; some 30,000 clay tablets have been found in Hattusa; they provide information on trade agreements, legal codes and procedures for ceremonies. Between the XVIth and the XIIIth centuries BC Hattusa was the capital of a large state which included most of the Anatolian plateau and northern Syria.

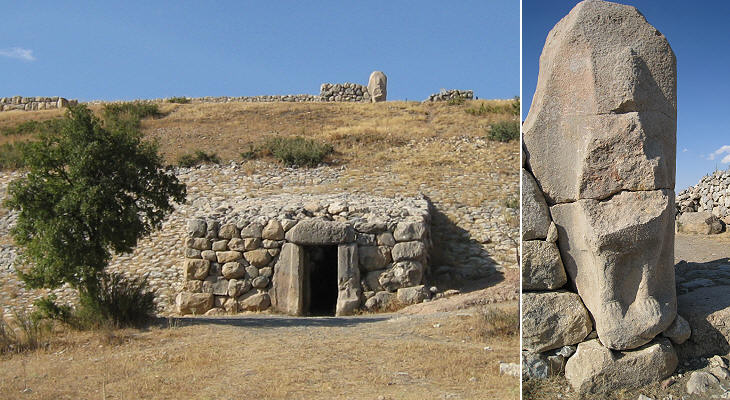

The Hittites had construction techniques based on three building materials: stone, timber and mud (unbaked) bricks. Stones were used for the foundations and for low walls which were completed by adding mud bricks; timber was used to support ceilings. This explains why the first impression a visitor has of Hattusa is that the city has vanished because only the stone part of its buildings remain. In order to show how Hattusa appeared in its heyday archaeologists have rebuilt a short stretch of the walls using the same materials and techniques of the Hittites.

At the very beginning Hattusa was limited to an isolated rock with an almost flat top. When Hattusa was enlarged to include first the Lower City and then the Upper City, the original settlement became the Royal Citadel (today's Buyuk Kale). Archaeologists have identified a series of courtyards surrounded by buildings which housed the court, the royal guards, the apartments of the king and archives of clay and wooden tablets; the latter are lost. The names of the various sites of Hattusa are modern and are generally based on the physical aspect of the rocks.

Two rugged rocks were included in the fortifications of Hattusa to protect its northern side. They were used as granary of an unusual type; storage rooms were dug into the rock floor and after having been filled with grain they were covered with a layer of earth.

At a later period Hattusa expanded southwards (Upper City). Sari Kale, another large rock, stood at the centre of this area. The Hittites fortified the rock and dug a cistern, but the remains of their buildings were modified in Byzantine times when a small settlement was located at the foot of the rock.

Yenicekale, a smaller rock to the south of Sari Kale, retains the artificial platform built by the Hittites.

The Upper City was (as the name suggests) placed on high ground, but for its defence the Hittites could not rely on cliffs and therefore they had to build a very long wall along its southern side. The Lion Gate stands in its western section: two rectangular towers flanked the entrance, a passage marked by exterior and interior portals. Both portals were fitted with pairs of heavy wooden doors; those at the exterior were most probably sheathed in bronze. The outer gate was decorated with two sculptured lions projecting from the pillars which supported a corbelled arch. They had a threatening appearance with wide open mouths.

The highest and southernmost point of the walls was strengthened by a huge rampart: at its top there was another monumental gate decorated with sphinxes; their presence is most likely due to the contacts between the Hittites and Egypt. At the foot of the rampart there is a small postern which through a long tunnel leads to the city. The image used as background for this page was taken inside the tunnel and it shows the corbelled technique used for its construction. The function of this postern is still uncertain. The theory that it was used for sallies is in contrast with the fact that the postern was in full view.

A third monumental gate was located at the eastern end of the southern wall: it is very similar to the Lion Gate with two towers protecting it. The relief decoration of this gate is on its interior: the sculpture of a warrior has been interpreted as portraying a king, but most likely it represented a god; the short dress does not fit very well with the ordinarily cold climate of Hattusa; this detail could be due to Egyptian influence.

A rock in a central position in the Upper City has a lengthy inscription at its base; the relief was very low and it is almost worn off; only some words have been deciphered. It is written in Luwian hieroglyphs, Luwian being a language which could be written both in cuneiform and hieroglyphic characters. It became very common in the last phase of the Hittite Empire. Archaeologists attribute the inscription to Shupiluliuma II, the last of the Great Kings of Hattusa and it probably was a list of his accomplishments, somewhat similar Index Rerum Gestarum Augusti.

This rock and its fortifications stand to the south of the Royal Citadel (Buyuk Kale); the fortifications belong to a period after the fall of the Hittite Empire; archaeologists have excavated the remains of a temple built by King Shupiluliuma II and in particular two small chambers one of which has reliefs in almost excellent condition. Move to page two. Introductory page Safranbolu Kastamonu Taskopru Amasya Turhal and Zile Tokat Niksar Clickable Map of Turkey showing all the locations covered in this website (opens in another window).     |