What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in August 2008. |

- Cappadocia - Goreme - Cappadocia - Goreme(Sultanhan) Cappadocia is a historical region of the Anatolian tableland which owes its name to the Persians. They were impressed by the number of horses they found in this region and thus called it Katpatuka, the land of beautiful horses. The boundaries of the region are marked by two extinct volcanoes: Mount Hasan (Hasan Dagi) near Nigde and Mount Argaeus (Erciyes Dagi) near Kayseri (you can see them in the introductory page). Between 9 and 3 million years ago these volcanoes erupted spewing enormous amounts of ashes and lapilli. These covered the ground and over time they solidified into tuff. Lava, which accompanied these ash eruptions, by its rapid cooling, formed blocks of basalt. While tuff is porous and subject to erosion, basalt is more resistant to the action of water and wind. This geological background explains the two main attractions of Cappadocia: a) the rocks turned into pillars, cones, obelisks and other extraordinary shapes by natural erosion; b) the tuffs carved out by man to form houses, churches and monasteries.

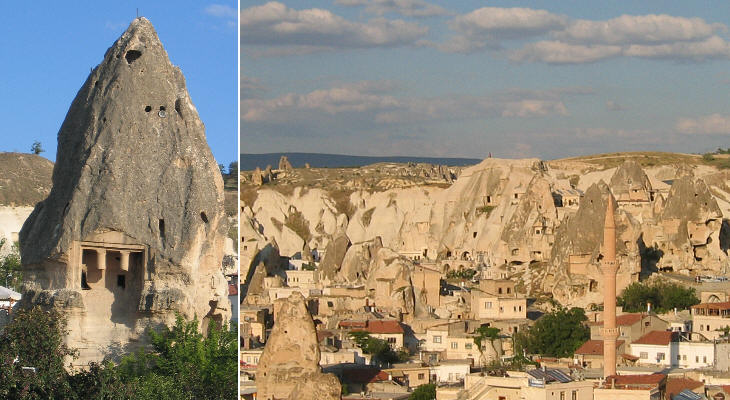

The village of Goreme, at the northern limit of Cappadocia, combines some of the most impressive naturally eroded rocks with carved out buildings. It has become a "must see" in all tourist packages covering Turkey: a typical Turkey Grand Tour includes Istanbul, Ankara, Hattusa, Goreme, Konya, Antalya, Pamukkale, Ephesus, Izmir, Pergamum and Canakkale.

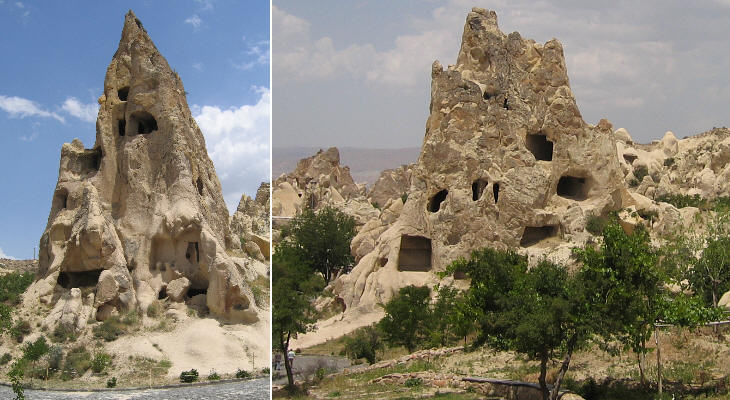

The phases of the erosion process can be seen at Goreme: in the first stage the rocks lose the superficial layer of ground; this uncovers the tuff which has a pink or white colour; these colours, combined with the initial smooth shapes caused by the erosion, create the impression of a semi-solid cream. In a second phase the rocks which are more resistant to erosion become isolated and their colour becomes dark.

The villagers of Goreme carved their dwellings, warehouses and stables out of the rocks. Today a certain number of modern buildings provide the facilities required by modern life and by the increasing number of tourists who visit the site. Turkish authorities have forbidden the construction of large hotels: these are placed on the tableland and do not spoil the view.

There is no evidence suggesting that Goreme was a sizeable village in antiquity; the rock-cut, Lycian style tomb shown above (not the only one) is probably due to the inhabitants of nearby Avanos who used Goreme as a necropolis.

Individual tourists can experience sleeping in a rock-cut room (having all modern comforts). They may also have a view of Goreme from balloons, although they may prefer to take pictures of them from the terrace of their hotel. Rooms do not need air-conditioning because the caves prove relatively warm and easy to heat during the cold Anatolian winters, and pleasantly cool during the hot summer months.

A striking aspect of the rock-cut houses of Goreme is that the inhabitants did not limit themselves to obtaining a certain number of rooms, but they actually emptied the whole rock with inner staircases connecting the various "apartments". This means that the villagers acquired a practical experience in determining whether the rock would collapse or not. You may wish to see another rock-cut village at Eski Gumus.

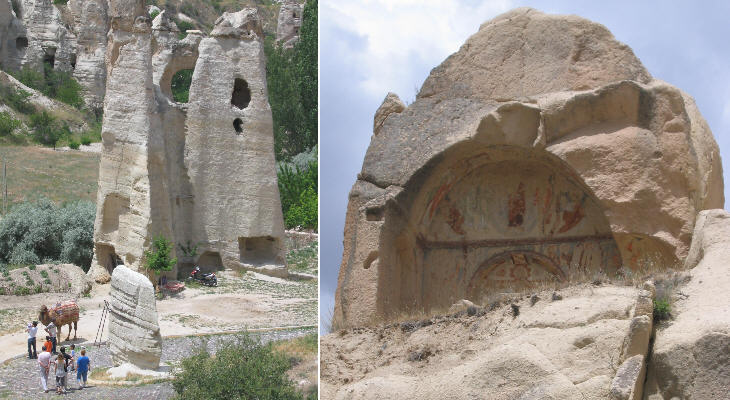

Monks and nuns established themselves in a site near Goreme where the erosion process was in its initial phase; cells, stables, utility rooms and many churches were cut into the rock; the churches were decorated with frescoes in a period which ranges from the late VIIIth century to the XIth century. After a long period of abandonment these monuments have become part of the Goreme Open Air Museum. Visitors are not allowed to take pictures using flash.

Over the centuries the rock has collapsed in several places, thus uncovering the inner structure of churches and monasteries. Although the spaces were the result of digging, yet they were shaped and decorated similar to ordinary buildings with pillars, columns and vaults.

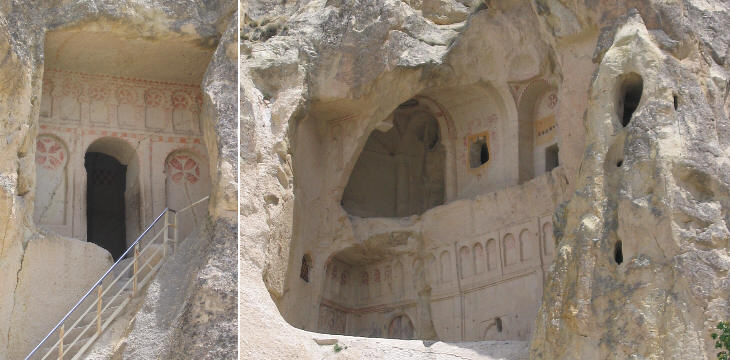

Usually the entrance to the churches was very small; this was not due to the desire to hide the church, but it was aimed at minimizing the exchange of air and retain a moderate temperature; ventilation shafts reaching the upper surface of the rock ensured that the smoke of fire and candles did not have intoxicating effects. In other parts of Cappadocia the inhabitants of some villages dug underground nets of rooms and stables; in this case the predominant reason was security and they did not care about decorating the ants' nests where they sought refuge.

A couple of churches were dug into isolated rocks. The entrance of the church shown above let in enough light to take a picture of its frescoes. One can see the effect of the many pebbles which were thrown at them, particularly at the faces of the saints. Other locations in Cappadocia: Uchisar Cavusin, Avanos and Urgup Ihlara Valley Move to: Introductory page Konya Karaman Mut and Alahan On the Way to Nigde Nigde Kayseri Sivas Divrigi Map of Turkey with all the locations covered in this website     |