What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in September 2003. |

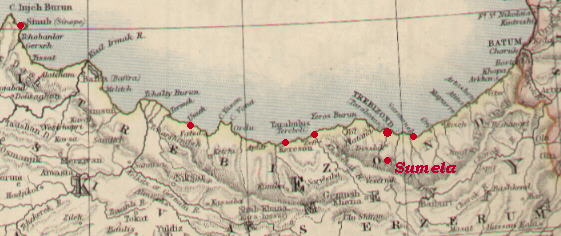

(Emperor Constantine VI in a fresco at Sumela) Introduction "On the fifth day they reached the mountain, the name of which was Theches. No sooner had the men in front ascended it and caught sight of the sea than a great cry arose, and Xenophon, in the rearguard, catching the sound of it, conjectured that another set of enemies must surely be attacking in front; for they were followed by the inhabitants of the country, which was all aflame; ... but as the shout became louder and nearer, and those who from time to time came up, began racing at the top of their speed towards the shouters, and the shouting continually recommenced with yet greater volume as the numbers increased, Xenophon settled in his mind that something extraordinary must have happened, so he mounted his horse, and taking with him Lycius and the cavalry, he galloped to the rescue. Presently they could hear the soldiers shouting and passing on the joyful word, "The sea! the sea!" From this place they marched in two stages and reached the sea at Trapezus, a populous Hellenic city on the Euxine Sea, a colony of the Sinopeans, in the territory of the Colchians. The men of Trapezus supplied the army with a market, entertained them, and gave them, as gifts of hospitality, oxen and wheat and wine. ...After this they met and took counsel concerning the remainder of the march. The first speaker was Antileon of Thurii. He rose and said: "For my part, sirs, I am weary by this time of getting kit together and packing up for a start, of walking and running and carrying heavy arms, and of tramping along in line, or mounting guard, and doing battle. The sole desire I now have is to cease from all these pains, and for the future, since here we have the sea before us, to sail on and on, 'stretched out in sleep,' like Odysseus, and so to find myself in Hellas." When they heard these remarks, the soldiers showed their approval with loud cries of "well said," and then another spoke to the same effect, and then another, and indeed all present." This is how Xenophon vividly described in his Anabasis the emotions his Greek soldiers felt when they saw Trebizond and the Black Sea after the long march from Babylon to the high mountains of eastern Anatolia through inhospitable lands. From Xenophon's account we learn that Trapezus (Trebizond) had been founded by settlers coming from Sinop and that the town was surrounded by the hostile Colchians. The progressive expansion of the Greeks in the Black Sea is symbolized by the myth of Jason who sailed with the Argonauts towards Colchis in search of the Golden Fleece. According to Strabo the Argonauts went in search of alluvial gold from the river Phasis, collected by the natives in fleeces laid on the river bed. A high range of mountains separate this coastal strip from the Anatolian tableland and this fact helped in maintaining the area under the rule of the Byzantine Empire, even when most of western and central Anatolia had been conquered by the Seljuks and other invaders coming from the east.

In 1185 a revolt in Constantinople put an end to the Comneni dynasty. Emperor Andronicus I, known for his cruelty, was torn to pieces in the hippodrome. The new dynasty of the Angeloi soon precipitated the empire into a deep crisis. Their dynastic quarrels led to the intervention of the crusaders (IVth Crusade), masterminded by the Venetians and in 1204 Constantinople fell and the empire collapsed. While most of the empire was partitioned among the leaders of the Crusade (with the Venetians gaining control of many Aegean islands), three regions remained under the control of Byzantine rulers: the Despotate of Epirus, the Empire of Nicaea and the Empire of Trebizond. The Empire of Trebizond was declared by a prince of the Comneni family, Alexius, who was helped by his family links with the rulers of Georgia. He fixed the seat of his empire at Trebizond, but he never abandoned his pretensions to the Byzantine throne. The empire included the coast of the Black Sea from Sinop to the border with the Kingdom of Georgia. Trebizond In the XIIIth century Trebizond played a key role in the trade between Europe and the Far East. In winter the passes in the high coastal range were closed, but during the summer seasonal caravans could reach Trebizond from the town of Erzurum in the Anatolian tableland. Erzurum was the terminal of two roads: one road reached Erzurum from Baghdad and it followed the Western Euphrates, the other road followed the Aras River and linked Erzurum with the Caspian Sea and Persia (Marco Polo followed this route when he returned from China to Europe). The Byzantine emperors of Trebizond were often at loggerheads with the Genoese and Venetian merchants, who had established trading posts in the Seljuk and Persian empires and wanted to make use of Trebizond to ship their goods to their colonies in Constantinople. Eventually the emperors of Trebizond had to accept Genoese and Venetian settlements in a fortified area near the harbour, outside the city walls.

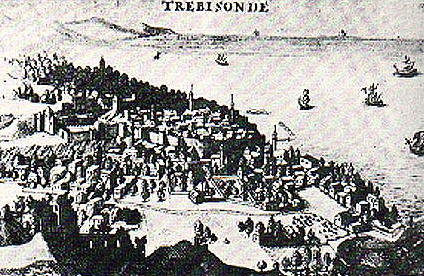

The XIXth century view above, shows the town of Trebizond protected by high walls and in the lower right corner the harbour facilities. Trebizond was made up by three adjoining towns: the Upper Town on a hill protected by two ravines, the Middle Town with the main churches and the Lower Town near the sea. Gates allowed the passage among the different towns.

The walls of the Upper Town have been less damaged by the modernization and expansion of the town, although parts of them are falling apart, while other sections have been totally rebuilt and look terribly modern.

The walls and gates of the Middle and Lower towns are in worse condition and when new bridges will increase the traffic in the area it will be very difficult to appreciate the charm of the past in modern Trabzon (the current name of Trebizond). The resources dedicated by the emperors to strengthening the walls of Trebizond were not justified by defense needs only. They wanted Trebizond to resemble as much as possible Constantinople, the walls of which were considered a sort of wonder of the world.

The crowning of a new emperor in Hagia Sophia in Constantinople was a highly complex ceremony, which the emperors of Trebizond tried to emulate. The name of the main church of Trebizond means Our Lady by the Golden Head, with a reference to the dome of the church which was covered by gilded metal. It is now a mosque, but its design, notwithstanding some changes, leaves no doubts about its former role. Again the typical three apses of the Byzantine churches indicate in the current Nakip Mosque, the former St. Andrew's church.

Relics of saints were highly valued and a cause of conflicts. The Venetians were very proud of having stolen the relics of St. Mark from Alexandria. The town of Bari erected a beautiful church to house the body of St. Nicholas, stolen from Myra in Lycia. Trebizond, unlike Constantinople, did not have any relics, but soon after the proclamation of the empire, the Byzantines found on the hill opposite the Upper Town, the skull and some bones of St. Eugene, who was declared holy protector of Trebizond (you may wish to have a look at the site of the (true) Order of St. Eugene of Trebizond and learn how Napoleon Bonaparte is thought to be a descendant of the Comneni - external link). The addition of a minaret did not turn St. Eugene into a mosque, at least from an architectural viewpoint.

Maybe the oldest church of Trebizond is St Anne's; a large ancient relief was utilized to carve there an inscription dating its foundation to Emperor Basil I (867-886).

Most of the monuments of Byzantine Trebizond look today somewhat displaced in the traffic and the modern buildings of a town rapidly growing in size. But one single monument has escaped this destiny and by itself it rewards the traveller for his long journey. Trebizond too had its Hagia Sophia, the emperors decorated it with reliefs and paintings and the church, after having been used as a mosque and a war hospital, was restored by Turkish authorities with the help of the University of Edinburgh and it is now a museum, surrounded by a peaceful garden.

The church has three large portals decorated with reliefs showing biblical scenes. The southern portal (not the main one which is shown in the image used as a background for this page) retains most of its decoration with motifs of grapes and images of Adam's sin.

A capital in the main portal shows eagles looking westwards and eastwards. The double-headed eagle was the symbol of the Byzantine Empire which spread from the west to the east. The Byzantine Empire was often torn by this dual soul, especially on religious matters. The Emperors of Trebizond used as standard the double-headed eagle of Byzantium, however after 1261 they recognized the new Byzantine Empire proclaimed by the Emperors of Nicaea following the reconquest of Constantinople and the eagle of Trebizond lost a head (relief on the apse of the church). However, after the fall of both the Byzantine Empire of Constantinople (1453) and the Byzantine Empire of Trebizond (1461), the marriage of a Comneni princess (Zoe "Sophia") to Ivan III the Great, Prince of Moscow, gave him the right to call himself Lord of all Russias and heir to the Byzantine Empire. His followers were to assume the title of caesars (tsars) and their standard showed the Byzantine double-headed eagle. The Austrian Emperors as heirs to the Sacred Roman Empire had also a standard showing the same eagle. The double-headed eagle is also a symbol of the Orthodox Church.

The paintings have vivid colours, still, and their design shows some western influence as they are not as rigid as in the traditional Byzantine style. The high drum of the dome lets in a lot of light. The pavement shows traces of the typical mosaics of Byzantine churches made using slices of columns and pieces of marbles from the ancient temples (this kind of decoration is frequent in many churches of Rome: e. g.: S. Maria Maggiore).

Notwithstanding the protection of St. Eugene and the highly noble origin of its emperors, the Empire of Trebizond was in a state of inferiority when compared with its powerful neighbours: the Seljuks, the Persians and, on the sea, Genoa and Venice. The first emperors tried to back their rights to the throne of Constantinople by enlarging their empire, but this backfired: they lost Sinop and Samsun. They had to accept the suzerainty of the Seljuks and later on of the Ottomans. This implied some sort of control over the Empire of Trebizond, which however retained its internal autonomy: in addition a yearly payment (tribute) acknowledged this submission and paid for protection and peace. The Ottomans until the end of the XIVth century were not very interested in maritime power and trade. Their military strength relied on cavalry armed with bow and arrows and their objective was to raid in search of booty. With the expansion of their possessions both in Anatolia and Europe they had to rely on the Genoese, the Venetians and even the Byzantines to move their forces quickly from one part to the other of their growing empire. However in the 1420s, Sultan Murat II expanded the Ottoman Empire into Albania and continental Greece threatening the Venetian strongholds along the Adriatic coast and in the Aegean Sea. The ensuing war with Venice dragged on for many years, because the two opponents did not know how actually to fight each other. Venice, whose power was at sea, did not have troops to attack the Ottomans by land. The Ottomans in turn were not able to stop the Venetians from supplying their fortresses. Murat II understood that to free his country from the influence of the maritime powers, which often managed to incite revolts and intervened in Ottoman dynastic quarrels, he needed to build a reliable fleet. His successor Mehmet II Fatih was even more convinced that the growth of the Ottoman Empire required the destruction of the maritime powers. Thus he planned the conquest of Constantinople, a source of continuous attempts to weaken the Ottomans by supporting rival sultans. First Mehmet II, arranged for his junior brother, Prince Kušuk Ahmet, to be killed as a means of avoiding internal disputes; then he moved and conquered Constantinople in 1453. A few years later, in 1461, he moved against the Genoese colonies on the Black Sea and easily conquered them. At this point, using the pretext of a delay in the payment of the yearly amount due to the Ottomans by the emperors of Trabizond, he invaded their empire and took their fortresses along the coast. The end of the Empire of Trebizond was totally bloodless. David, the last emperor, apologized for being late in his payments, claiming that the revenue he got from his empire was so reduced that he could not meet his obligation and he offered his empire to Mehmet II in return of a yearly amount for him and his successors. Thus ended the last empire which claimed to be the heir to the Roman Empire. The former emperor settled in Constantinople, while his son converted to Islam and lived in a palace near Galata, the area was named after him Beyoglu. Most likely the decision made by the last emperor aknowledged the fact that he had no hope of resisting the Ottoman forces and that the Byzantine heritage could only be preserved by influencing the Ottoman rulers from within. A Byzantine princess of Trebizond was married to one of Mehmet's sons. Their child was to become Sultan Selim I (the Cruel), who conquered the Arab world from Mecca to Cairo.

The Byzantine princess was known for her compassion (maybe counterbalancing the cruelty of her son) and the help she provided to the poor. In her honour Selim I built a tomb and a fine mosque with a gentle name: the mosque of the Pink Lady of Spring. Selim I was just one of a long list of sultans born of Christian or Jewish mothers, either princesses of Christian vassals or slaves.

For a while Trebizond retained under the Ottoman rule its importance as a trading post and other mosques embellished the town. Not for a long time however, because the Genoese, after having lost their colonies on the Black Sea, in the search for alternative routes, financed the expeditions of the Portuguese, which eventually reached first the Cape of Good Hope and later on the coasts of Malabar and Calcutta. In 1502 the Portuguese fleet blockaded the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf to force all trade between India and Europe to use the route that it controlled. An attempt to beat the Portuguese by the Ottoman fleet in 1538 ended with the conquest of Yemen and Aden, but left untouched the Portuguese control of the trade route.  Move to: Sumela Monastery Byzantine Fortresses in the Empire of Trebizond Clickable Map of Turkey showing all the locations covered in this website (opens in another window).     |