What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in September 2009. |

Sumela Monastery Sumela Monastery

This page is a short account of a visit made to the monastery of Sumela in July 2003. The monastery is located some 30 miles south of Trebizond in a valley covered by forests. The road reaches an area with shops and restaurants at the bottom of the valley. From this point there are two alternative routes to reach the monastery: a) a path through the wood on the same side of the mountain where the monastery is located; b) a road on the other side of the mountain and then a path to reach the monastery. I went up following the path through the wood.

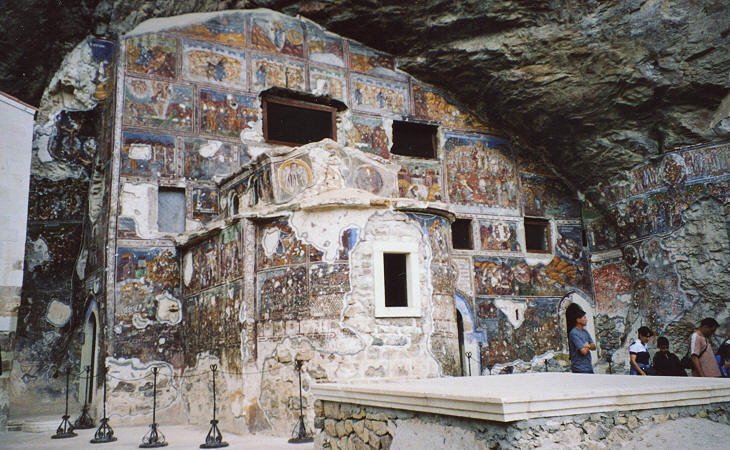

After some twenty minutes' walk almost in the dark as the wood is very thick, an unexpected clearing allows the traveller to see the monastery almost hanging on his head. A gigantic rock stands behind the monastery and you cannot avoid feeling that they could both fall on you.

The access to the monastery is through a narrow gate at the top of stairs cut into the rock. One does not see the monastery and the gate seems to lead inside the mountain (I had a similar impression when I visited Sacro Speco the monastery founded by St. Benedict near Subiaco in Italy). Once I went through the gate I was totally surprised by what I saw, as the entrance leads to the top storey of the monastery to a sort of piazzetta in a cavity of the mountain. A group of chapels and other tiny buildings scattered in an apparently haphazard manner, reminded me of the models of the manger-scene in Bethlehem, which are so popular in Italy.

The monastery was under the protection of the Emperors of Trebizond, but the fall of the empire did not entail the end of the monastery. A large Greek community continued to live in Trebizond, mainly involved in trading activities. In Trebizond the main churches had been turned into mosques and the Greeks who had maintained their Orthodox faith were obliged to meet in tiny and almost hidden churches. The monastery, miles distant from the nearest village, was not seen by the Ottoman rulers as a defiance to Islam and so the Greek community of Trebizond was allowed to support the monks living in the monastery.

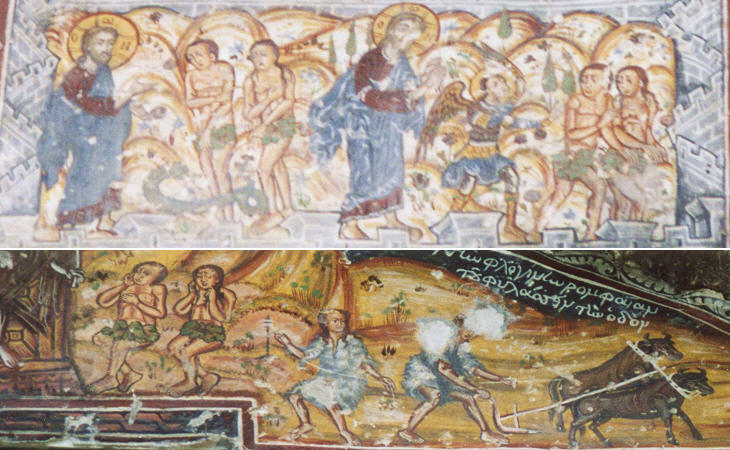

The main chapel is a very strange building: part of it is cut into the rock, while the apse is made of brickwork which comes out of it. The interior is fully decorated with frescoes some of which date back to the XVth century and show some emperors of Trebizond. What is unusual is the fact that the exterior is painted too and even the rock around the church is covered with paintings (in general XVIIIth century paintings) as if the Greeks had selected this hidden location to recreate that vast sacred iconography which once they could admire in their many churches in Trebizond.

One of the paintings in better condition shows the IInd Ecumenical Council of Nicaea, held in that town (of which the painting shows the walls) in 787 to put an end to the iconoclastic controversy which was tearing apart the Byzantine Empire; eventually the council admitted the worship of images in churches, but it did not stop the opposite factions from killing and performing various atrocities aimed at those who held a different opinion. The painting is interesting as it shows the role of the Emperor (Constantine VI), who presided over the Council and manoeuvered to obtain the resolution he supported. It is clear evidence that the Byzantine emperors are the best known example of caesaropapism, a political system in which the head of the state is also the head of the church and supreme judge in religious matters. It seems a theory dead and buried in the past, nevertheless 2003 showed that there are politicians who (I guess totally unconsciously, as they do not appear particularly knowledgeable in philosophical matters) are caesaropapism supporters, as they easily talk about evil, crusades and knowing on whose side God stands.

The hollow rock protects the paintings from rain and snow, but it could not protect them from the stones that young shepherds threw at them to test their aim after the monastery was abandoned as a result of World War I and the events following its end.

Relationships between Ottoman rulers and Greek subjects after the fall of the last Byzantine states were generally good and most Greek historians have come to the conclusion that the Greeks preferred to live under the Ottomans, than under the Venetians. The Sultans did not enforce conversion to Islam, nor did they impose the religious law (Seriat) derived from the Koran. This law dealt mainly with personal behaviour and community life. The Orthodox, Jewish and Armenian millet (families) were allowed to follow their own rules (established by their religious authorities) as long as they respected the laws issued by the Sultan in financial and state organization matters. The practice for which the Ottomans are most often reproached i.e. the detachment of young Christians from their families to be converted to Islam and trained in the Janissary corps, was counterbalanced by the fact that the other children of the Christian peasants were not subject to service in the army. In comparison with the atrocities of the Religion Wars in Western Europe, the Ottoman system proved to be very tolerant. The situation changed in the second half of the XVIIIth century, partly because the Greek subjects started to see in the growing power of the Russian Empire the force which could beat the Ottomans and restore a Christian (Orthodox) emperor on the throne of Constantinople. Although the Greeks living in Trebizond were very far from the sites of the initial Greek struggle for independence, they too started to believe in the restoration of the ancient Byzantine Empire (the so called Megalo Idea - great idea). The Russian Empire had expanded to Transcaucasia (Georgia) and conquered the province of Kars, not far from Trebizond when World War I led to a new conflict between the two empires. In 1916 the Russians occupied Trebizond and the Greeks felt they had been liberated, but in February 1918 the treaty of Brest-Litowsk returned Trebizond to the Ottomans. In November of the same year, together with Germany, Austria and Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire surrendered and the winners started to carve new countries out of its dead body (Syria, Iraq, Kuwait, etc.). The Anatolian peninsula was split into areas of influence. The Greeks of Trebizond proclaimed the Republic of Pontus. At this point XIXth century nationalism which had brought about the collapse of the multinational Ottoman Empire (as well as the Austrian Empire), rapidly developed among Turkish people. MustafÓ Kemal (who later on assumed the surname of Ataturk - father of the Turks) led a growing reaction to the occupation of many Anatolian districts and eventually defeated the Greeks, south of Ankara, forcing them to abandon the area they had occupied around Smyrna. The treaty between the newly born Republic of Turkey and Greece was based on the assumption that the two communities could no longer live together. A transfer of population (approximately 2,000,000 people) between the two countries was agreed. The heirs of Jason left Trebizond after more than 2,000 years and returned to Greece. The Monastery of Sumela was abandoned and only its being so far from populated areas and hidden in thick forests partially saved it. Today it is a Museum and it is being restored (in my modest opinion: excessively restored).

The road by which I returned to my dolmus (the little van - 10/16 seats - which is the backbone of the Turkish transportation system) crossed a singing brook several times. It was a refreshing sound, most needed because the valley, as well as Trebizond, is very humid and although the temperature is not high, travellers are bound to frequently perspire.

Move to: Trebizond Byzantine Fortresses in the Empire of Trebizond Clickable Map of Turkey showing all the locations covered in this website (opens in another window).  SEE THESE OTHER EXHIBITIONS (for a full list see my detailed list).    |