What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in November 2013. |

- Petra in Burckhardt's account - part two - Petra in Burckhardt's account - part two

(left: J. L. Burckhardt in Arab attire in a XIXth century engraving; right: the Treasury of Petra) If you came to this page directly you might wish to read part one first. From this place, as I before observed, the Syk widens, and the road continues for a few hundred paces lower down through a spacious passage (Outer Syk) between the two cliffs. Several very large sepulchres are excavated in the rocks on both sides; they consist generally of a single lofty apartment with a flat roof; some of them are larger than the principal chamber in the Kaszr Faraoun. On the outside of these sepulchres, the rock is cut away perpendicularly above and on both sides of the door, so as to make the exterior facade larger in general than the interior apartment. Their most common form is that of a truncated pyramid, and as they are made to project one or two feet from the body of the rock they have the appearance, when seen at a distance, of insulated structures. On each side of the front is generally a pilaster, and the door is seldom without some elegant ornaments. J. L. Burckhardt - Travels in Syria and the Holy Land - 1822

Of those which I entered, the walls were quite plain and unornamented; in some of them are small side rooms, with excavations and recesses in the rock for the reception of the dead; in others I found the floor itself irregularly excavated for the same purpose, in compartments six to eight feet deep, and of the shape of a coffin; in the floor of one sepulchre I counted as many as twelve cavities of this kind, besides a deep niche in the wall, where the bodies of the principal members of the family, to whom the sepulchre belonged, were probably deposited.

The fronts resemble those of several of the tombs of Palmyra, but the latter are not excavated in the rock, but constructed with hewn stones. I do not think, however, that there are two sepulchres in Wady Mousa perfectly alike; on the contrary, they vary greatly in size, shape, and embellishments. In some places, three sepulchres are excavated one over the other, and the side of the mountain is so perpendicular that it seems impossible to approach the uppermost, no path whatever being visible; some of the lower have a few steps before their entrance.

In continuing a little farther among the sepulchres, the valley widens to about one hundred and fifty yards in breadth. Here to the left is a theatre cut entirely out of the rock, with all its benches. It may be capable of containing about three thousand spectators: its area is now filled up with gravel, which the winter torrent brings down. The entrance of many of the sepulchres is in like manner almost choked up. There are no remains of columns near the theatre.

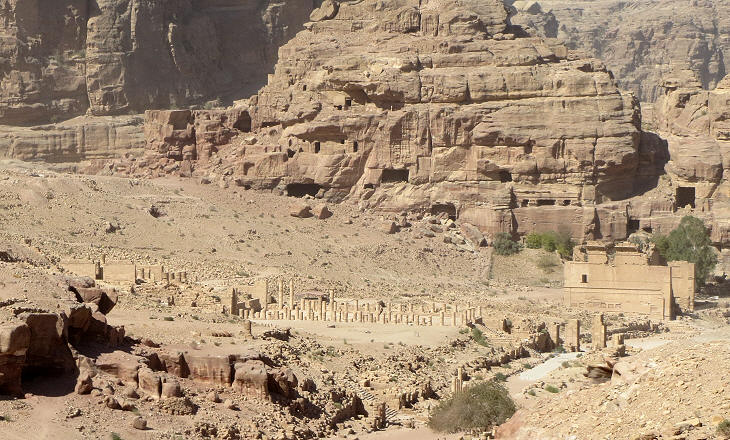

Following the stream about one hundred and fifty paces further, the rocks open still farther, and I issued upon a plain two hundred and fifty or three hundred yards across, bordered by heights of more gradual ascent than before. Here the ground is covered with heaps of hewn stones, foundations of buildings, fragments of columns, and vestiges of paved streets; all clearly indicating that a large city once existed here; on the left side of the river is a rising ground extending westwards for nearly a quarter of an hour, entirely covered with similar remains. On the right bank, where the ground is more elevated, ruins of the same description are also seen. In the valley near the river, the buildings have probably been swept away by the impetuosity of the winter torrent; but even here are still seen the foundations of a temple, and a heap of broken columns.

The finest sepulchres in Wady Mousa are in the eastern cliff, in front of this open space, where I counted upwards of fifty close to each other. High up in the cliff I particularly observed one large sepulchre, adorned with Corinthian pilasters.

Farther to the west the valley is shut in by the rocks, which extend in a northern direction; the river has worked a passage through them, and runs underground, as I was told, for about a quarter of an hour. Near the west end of Wady Mousa are the remains of a stately edifice, of which part of the wall is still standing; the inhabitants call it Kasr Bent Faraoun, or the palace of Pharaoh’s daughter. In my way I had entered several sepulchres, to the surprise of my guide, but when he saw me turn out of the footpath towards the Kasr, he exclaimed: “I see now clearly that you are an infidel, who has some particular business amongst the ruins of the city of your forefathers; but depend upon it that we shall not suffer you to take out a single para (Ottoman coin which was used as the basic unit of account for small transactions) of all the treasures hidden therein, for they are in our territory, and belong to us.” I replied that it was mere curiosity, which prompted me to look at the ancient works, and that I had no other view in coming here, than to sacrifice to Haroun; but he was not easily persuaded, and I did not think it prudent to irritate him by too close an inspection of the palace, as it might have led him to declare, on our return, his belief that I had found treasures, which might have led to a search of my person and to the detection of my journal, which would most certainly have been taken from me, as a book of magic. It is very unfortunate for European travellers that the idea of treasures being hidden in ancient edifices is so strongly rooted in the minds of the Arabs and Turks; nor are they satisfied with watching all the stranger’s steps; they believe that it is sufficient for a true magician to have seen and observed the spot where treasures are hidden (of which he is supposed to be already informed by the old books of the infidels who lived on the spot) in order to be able afterwards, at his ease, to command the guardian of the treasure to set the whole before him. It was of no avail to tell them to follow me and see whether I searched for money. Their reply was, “of course you will not dare to take it out before us, but we know that if you are a skilful magician you will order it to follow you through the air to whatever place you please.” If the traveller takes the dimensions of a building or a column, they are persuaded that it is a magical proceeding. Even the most liberal minded Turks of Syria reason in the same manner, and the more travellers they see, the stronger is their conviction that their object is to search for treasures.

On the rising ground to the left of the rivulet, just opposite to the Kasr Bent Faraoun, are the ruins of a temple, with one column yet standing to which the Arabs have given the name of Zob Faraoun, i.e. "hasta virilis (man's lance) Pharaonis"; it is about thirty feet high and composed of more than a dozen pieces.

From thence we descended amidst the ruins of private habitations, into a narrow lateral valley, on the other side of which we began to ascend the mountain, upon which stands the tomb of Aaron. There are remains of an ancient road cut in the rock, on both sides of which are a few tombs. After ascending the bed of a torrent for about half an hour, I saw on each side of the road a large excavated cube, or rather truncated pyramid, with the entrance of a tomb in the bottom of each. Here the number of sepulchres increases, and there are also excavations for the dead in several natural caverns.

A little farther on, we reached a high plain called Szetouh Haroun, or Aaron’s terrace, at the foot of the mountain upon which his tomb is situated.

The sun had already set when we arrived on the plain; it was too late to reach the tomb, and I was excessively fatigued; I therefore hastened to kill the goat, in sight of the tomb, at a spot where I found a number of heaps of stones, placed there in token of as many sacrifices in honour of the saint. While I was in the act of slaying the animal, my guide exclaimed aloud, “O Haroun, look upon us! it is for you we slaughter this victim. O Haroun, protect us and forgive us! O Haroun, be content with our good intentions, for it is but a lean goat! O Haroun, smooth our paths; and praise be to the Lord of all creatures!” This he repeated several times, after which he covered the blood that had fallen on the ground with a heap of stones; we then dressed the best part of the flesh for our supper, as expeditiously as possible, for the guide was afraid of the fire being seen, and of its attracting hither some robbers.

August 23rd, 1812 - My guide insisted upon my speedy return; (..) I therefore complied with his wishes, and we returned by the same road we had come. The image used as background for this page shows the most common decoration of tombs. Return to page one or read notes and comments on Petra. Move to: Introductory Page Ajlun Castle and Pella (May 3rd, 1812) Amman and its environs (July 7th, 1812) Aqaba "Castles" in the Desert (incl. Qasr el-Azraq) Jerash (May 2nd, 1812) Madaba (July 13th, 1812) Mt. Nebo and the Dead Sea (July 14th, 1812) On the Road to Petra (incl. Kerak and Showbak) (July 14th - August 19th, 1812) Umm al-Jimal Umm Qays (May 5th, 1812)

|