What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in August 2011. |

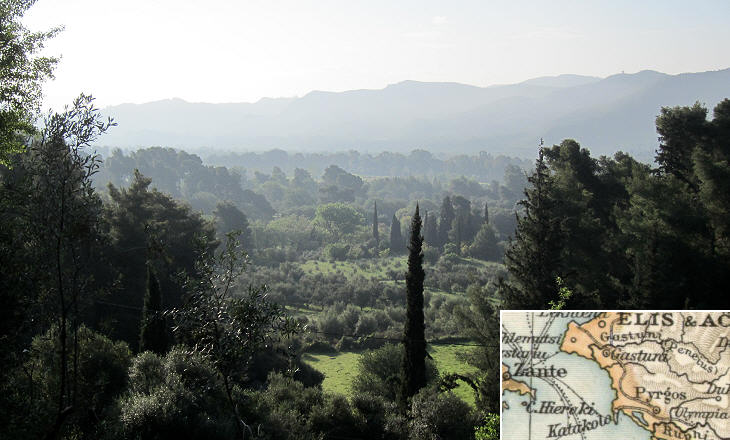

- Olympia: The Foundation of the Olympic Games - Olympia: The Foundation of the Olympic Games(Wrestlers in a relief at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens) Olympia is located in Elis, a region on the Ionian coast of Peloponnese facing the isle of Zante, which is named after the ancient town of Elis. This town was a member of the Peloponnesian League which was controlled by the Spartans, but in 420 BC Elis defected in favour of Athens; the Spartans invaded the region and in 397 BC they destroyed the town.

Today the agricultural sector is the backbone of the economy of Elis; the coastal plain is intensively farmed with large use of greenhouses; reforestation plans implemented by the Greek government have given an almost Tuscan appearance to the hills surrounding Olympia. In antiquity Elis was known for its cattle and horses and for the Fifth Labour of Hercules: the divine hero was asked whether he would be able to clean the stables of Augeias, King of Elis, in just one day; it was a very challenging task because the dung had not been cleared away for thirty years. Hercules undertook this labour with the promise of one tenth of the cattle as the reward; he then breached the walls of the yard and he diverted the Alpheius and Peneius Rivers so that their streams swept the yard clean.

According to the Greek poet Pindar (Vth century BC) the Olympic Games were founded by Hercules following the completion of the Fifth Labour and the slaying of King Augeias who refused to pay the promised reward. After the conquest of Elis, Heracles (aka Hercules) established the famous four-yearly Olympic Festival and Games in honour of his father Zeus. Having measured a precinct for Zeus and fenced off the Sacred Grove, he stepped out the stadium, named a neighbouring hillock "the Hill of Cronus", and raised six altars to the Olympian gods: one for every pair of them. (..) Being much plagued by flies on this occasion, he offered a sacrifice to Zeus the Averter of Flies, who sent them buzzing across the Alpheius River (Robert Graves - The Greek Myths).

Stadion is an ancient Greek unit of length equal to 600 feet and the same word designated a running race of such a length; the earliest record of the Olympic Games being held is dated 776 BC and the stadion was its only event; when other events were added the stadion remained the most important competition and the Games were named after the winner of this race.

Archaeologists have identified two racing grounds for the stadion which were utilized before the one shown above which was built in the Vth century when Olympia was enlarged; the audience sat on temporary timber structures which on their northern side exploited the natural slope of the hill; in the IIIrd century BC a vaulted passage was built for the athletes to make their entrance into the racing ground. Starting and finishing lines were also utilized as turning points in two other races which were added to the stadion: diaulos (twice the stadion) and dolichos (a long-race of maybe 18 stadion). The marathon is a long race which was introduced at the First Modern Olympic Games (1896) and which was unknown as a sporting event to the ancient Greeks.

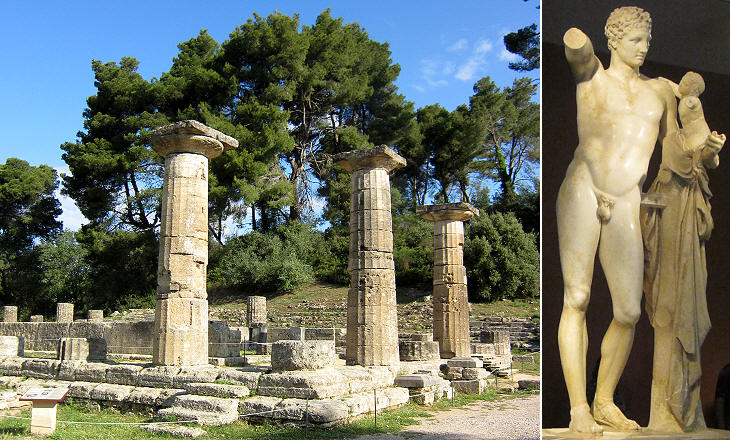

According to the mythological account Hercules dedicated a Sacred Grove to Zeus; it was a piece of land reserved for the worship of the god; the trees of the grove were most likely oaks, similar to what can be seen at Dodoni, one of the most ancient Greek oracles. Over time sacred groves were replaced by temples with columns representing the trees; at Olympia this occurred in 468-456 BC; the cell containing the statue of Zeus was surrounded by 34 Doric columns (6 on the two fronts and 11 on the sides); the entrance was placed on the eastern side.

The temple was built with local limestone coated with plaster to give it the appearance of marble; in 426 AD Emperor Theodosius II ordered the destruction of the temple, but this probably did not affect its structure which collapsed in the following century when two earthquakes struck the region; over time landslips and floods covered the ruins with a thick layer of mud.

In 1829 a French team initiated excavating the site and found some reliefs which were brought to Paris. The anonymous sculptor is referred to as the "Olympia Master" or the "Master of the Temple of Zeus".

The Temple to Zeus housed a chryselephantine (made up of gold and ivory parts) statue of the god by Phidias which was made in a workshop built for the purpose and which had the size of the cell. The statue consisted of a wooden structure covered by slabs of ivory and sheets of gold leaf; the ivory represented the flesh while gold was used for garments and hair (and precious stones for details such as the eyes); chryselephantine statues had a very high status in the ancient world; Phidias also made the chryselephantine statue of Athena in the Parthenon of Athens. The precious materials of these statues caused their destruction; that of Zeus (which was included among the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World) was transferred to Constantinople when Emperor Theodosius II decreed the destruction of the temple; it was used to embellish the house of Lausus, his powerful eunuch (and this says a lot about the true objective of Theodosius' decision); it was eventually destroyed in a fire in 475 (a Roman copy in marble and bronze can be seen at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg - external link).

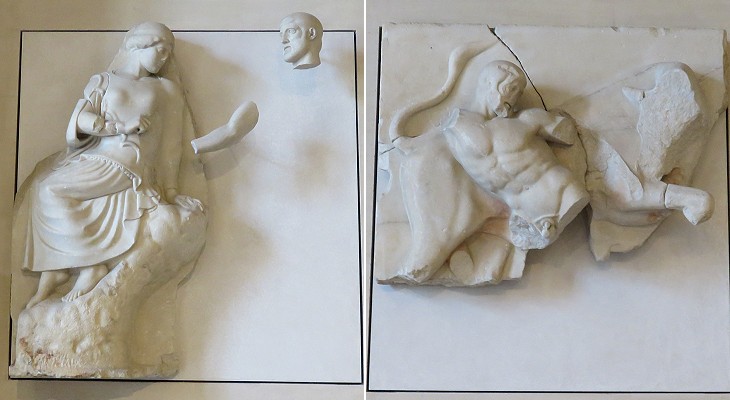

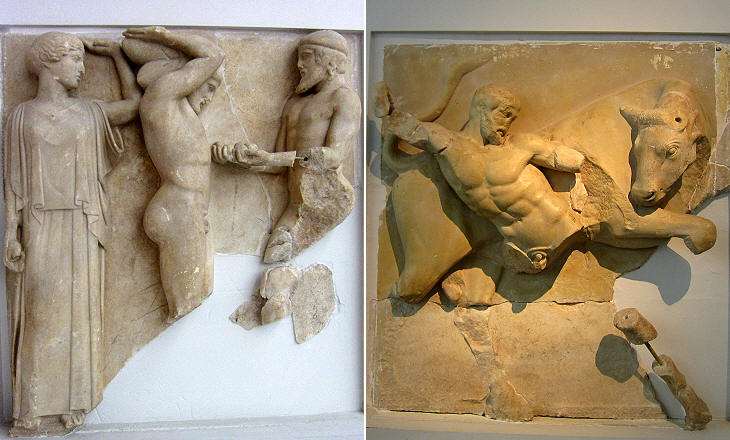

The decoration of the two fronts occurred soon after the construction of the temple; the overall meaning of the two scenes is a celebration of justice and impartiality, perhaps an appeal to the athletes to compete fairly. The statues on the eastern front are associated with another myth related to the foundation of the Olympic Games: they show Zeus acting as impartial arbiter in a chariot race between Oenomaus and Pelops; Oenomaus was told in a prophecy that he would be killed by his son-in-law; he therefore decreed that Hippodamia would marry the man able to beat him in a chariot race; he took no risks because his mares were the best in Greece. Thirteen pretenders had already failed to win the race when Pelops sued for the hand of Hippodamia; he managed to bribe Oenomaus' charioteer who tampered with the axles; during the race Oenomaus' chariot broke apart and the king was killed; Pelops won the race, married Hippodamia, founded a large kingdom to which he gave his name (Peloponnese) and started the Olympic Games.

According to tradition (and Homer: Phoebus, the long-haired god - Homeric Hymn to Demeter - 133) Apollo had long hair reaching his shoulders, but the god portrayed at Olympia has the neatly arranged snail curls of the athletes (see the icon and the image in the background of this page); similar to Zeus on the other front Apollo appears as being impartial in the fight; it is a very unusual portrait of the god whose iconography shows him in active roles from slaying Marsia to playing the cither or chasing Daphne.

The statues were executed in marble from Paros and were attributed to several different sculptors, but they are now thought to be the work of a local Master of Olympia. The statues were meant to be seen from below and at some distance; from this respect their current positioning in the Museum of Olympia is slightly misleading.

The metopes on the exterior of the temple were plain, but those inside the front (pronaos) and rear (opisthodomos) porticoes were decorated with reliefs depicting the Labours of Hercules, who was involved in the foundation of the Olympic Games.

In the 1958 Introduction to The Greek Myths, Robert Graves wrote: ... an educated person is now no longer expected to know (for instance) who Deucalion, Pelops, Daedalus (..) may have been. (..) at first sight this does not seem to matter much, because for the last two thousand years it has been the fashion to dismiss the myths as bizarre and chimerical fancies, a charming legacy from the childhood of the Greek intelligence, which the Church naturally deprecates in order to emphasize the greater spiritual importance of the Bible. Yet it is difficult to overestimate their value in the study of early European history, religion, and sociology. Hera (Juno) in the common knowledge is a sort of desperate housewife continuously upset by discovering that Zeus (Jupiter), her husband, is spending his time on seducing nymphs and boys. At Olympia however the temple dedicated to Hera was erected before that to Zeus, which indicates that the goddess was venerated at least as much as her husband; female deities as symbols of fertility prevailed in the ancient Greek society which was made up of herdsmen and farmers until the country was invaded by warrior tribes (chiefly the Dorians) who introduced male deities. The classic Greek pantheon indicates the compromise reached by the two cultures: six gods and six goddesses headed by Zeus and Hera.

While the worship of Hera dates from antiquity, that of Hermes developed at a later time; according to the myth he was the twelfth and last Olympian god; the unearthing in 1877 of a statue of Hermes in the Heraion indicates that the building at one point was turned into a pantheon where several gods were worshipped. The statue is thought to be a Roman copy of an original traditionally attributed to Praxiteles; the god was portrayed in the act of holding infant Dionysus. A similar statue of Hermes was found in Rome in the XVIth century; it was highly praised by Gian Lorenzo Bernini and it influenced many of his works.

It was customary for important towns to build small temple-like treasuries in locations which were representative of the overall Greek world; buildings of this type housed votive offerings. While at Delphi, with the exception of Taras (today's Taranto in southern Italy), the treasuries were built by towns in mainland Greece or on the Aegean islands, the treasuries at Olympia were built mainly by towns at the periphery of the Greek world such as Byzantion (Constantinople), Cyrene in Libya and Syracuse, Sybaris, Selinus, Metapontium and Gela in Sicily or southern Italy. The treasuries were built in a row to the north of the first racing ground.

Honorary columns were a particular type of votive offerings; the statue of Nike (Victory) was a gift to Olympia made in 425 BC by the Messenians, the inhabitants of a town near today's Kalamata, and by those of Nafpaktos. The flying goddess was portrayed in the act of landing and in order to emphasize the dynamic impact of the statue it was placed on a triangular pedestal. It is the only work which can be attributed to Paeonius of Mende and it marks a moment of the passage between Classic and Hellenistic sculpture; it probably influenced the design of the Nike found at Samothrace.

Go to page two: Hellenistic and Roman periods Clickable Map of the Ionian and Aegean Seas with links to other locations covered in this website (opens in a separate window)

|