What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in July 2011. |

- Palmyra - Other Monuments - Palmyra - Other Monuments

This page covers temples (other than the Temple of Bel), public facilities and some other monuments of Palmyra. If you came to this page directly, you might wish to read an introductory page first.

Baal Shamin was a deity of Phoenician origin; it had the epithet of Lord of Heaven, in the sense that the weather depended on its mood; for this reason its cult spread toward the Hauran region in southern Syria which was intensely farmed and where lack or excess of rain were very important; the cult of Baal Shamin reached Palmyra probably because Phoenician merchants settled there. The Temple of Baal Shamin was built shortly after the visit made by Emperor Hadrian to the city in 129 AD (this is known from an inscription where a donor for the erection of the temple indicates he paid for the stay of the emperor's retinue at Palmyra). Dedicatory inscriptions celebrating the construction of altars, columns and courtyards which surrounded the temple date from 23 AD to 106.

In most of the inscriptions Baal Shamin was referred to with a second name Du-Rahlun, the god from Rahle, a location which has been identified as Mt. Hermon in the Anti-Lebanon Mountains. The devotees of Baal Shamin settled at Palmyra after other ethnic groups and this explains why the temple they built was located at a certain distance from the Colonnade, the heart of the ancient city. Baal Shamin was eventually worshipped together with the other deities as the following inscription demonstrates: This is the relief that Shewira son of Taima and Male son of [ … ] have made for Bel and Baal Shamin and for Aglibol and for Malakbel and for Astarte and for Nemesis and for Arsu and for Abgal, the good and rewarding gods for the life of themselves and the life of their sons. In the month Kanun of the year 464 (= November 152 AD). Peace!

The temple dedicated to Nebo was built approximately at the same time as that to Baal Shamin, but it was erected in a much more prestigious location i.e. between the Great Arch of the Colonnade and the Temple of Bel; Nebo was a deity of Babylonian origin; archaeologists have found out that festivals were held at this temple; in bilingual inscriptions Nebo was usually associated with Apollo and it appears that priests of Nebo issued oracles similar to those at Greek sanctuaries dedicated to Apollo, such as Delphi and Delos. The image used as background for this page shows a decorative element found near this temple.

A series of temples were located at the opposite end of the city to those of Bel and Nebo. This second group of temples was dedicated to Arab deities and in particular to Allat, a goddess who was associated to Athena. These temples were in part modified when Emperor Diocletian built the camp for of a Roman garrison near them. Allat, similar to Athena, was portrayed as a warrior goddess, but also seated between two lions or with a lion at her side (see a relief found at Palmyra - external link); this iconography was interpreted as a symbol of victory or dominance and it appeared on the back of coins issued by Roman emperors; it eventually became the traditional representation of Britannia in the heydays of the British Empire. The name of the young son of Queen Zenobia was Wahb Allat which means Gift of Allat.

The main entrance to Palmyra was located to the south of the city; it was the arrival point of caravans coming from the valley of the Euphrates River and carrying goods from the ports on the Persian Gulf; it seems that the merchants of Palmyra had total control of the trade along this route, while merchants of other towns took care of shipping the goods westward to their final destinations.

The Palmyra Municipality levied a tax on all goods which entered or exited the city; clearance of duties occurred in a hall near the Agora; archaeologists have found tablets of tables of the time of Emperor Antoninus Pius which stated the duties which were to be paid. The tablets are now in St. Petersburg - external link; they provide an interesting insight into the economy of Palmyra and more in general into that of the Roman Empire (amounts were expressed in Roman denarii, silver coins). From them we learn that a male slave paid a duty of 22 denarii, a camel-load of aromatic oil 25 denarii and a camel-load of olive oil 10 denarii. The purpose of the inscription was that of granting transparency to the taxation in order to avoid quarrels between merchants and tax collectors.

The commercial heart of Palmyra was a quadrangular walled area surrounded on the inside by a portico, the columns of which had pedestals with small statues of emperors and members of their families, city officers, wealthy merchants and caravan leaders. The Agora, similar to the Roman Forum was the meeting place of the most important citizens, who in Palmyra were merchants; it is unlikely that camels and donkeys were admitted into the Agora, so the reference to it as a marketplace is correct only in the sense that trade agreements were reached there.

A hall on one side of the portico was used for banquets, either for official ceremonies or for business meetings; the attendees lay on benches along the walls in the posture we see in many funerary monuments. Apparently many aspects of life at Palmyra revolved around banquets, which, although they often took place in halls adjoining temples, were not necessarily related to religious ceremonies. The many reliefs, statues and paintings found at Palmyra indicate that its inhabitants had a predilection for banquets and they were very rarely involved in other activities such as exercising or making sacrifices.

Another small hall adjoining the Agora is commonly known as the Senate, because of a small horseshoe bench; it was most likely a meeting room for the officers in charge of the Agora, but, because, at least initially, the society of Palmyra had a tribal structure, it could also have been the hall where the chieftains met. The Senate and the Agora were located near the Tetrapylon which marked almost exactly the midpoint of the Colonnade which crossed Palmyra.

The Theatre is located near the Agora and it was built on flat ground in the IInd century AD; it was never completed and this explains the lack of proportion between the width of the stage, which is almost as wide as that of Bosra, and the limited number of rows where the audience sat, even assuming that there were more than those reconstructed.

The main entrance to the stage had a small terrace on its top; most likely the original design of the theatre included a higher "proscaenium", the decorated wall behind the stage; some sources claim that the theatre was greatly damaged when Emperor Aurelian conquered the city in 273 and that it was reconstructed only in part.

Usually Roman baths are among the buildings which have best stood the ravages of time; this however did not occur at Palmyra, probably because the Roman construction techniques based on fired bricks and mortar were not employed, nor were used arches and vaults to strengthen the large halls of these buildings; the entrance to the baths was preceded by a portico with four granite columns which were erected at the time of Emperor Diocletian. These heavy columns could not be transported using camels or donkeys; it was necessary to arrange an ox train which needed seventeen days to reach Palmyra from Emesa (today's Homs) and even more from Damascus.

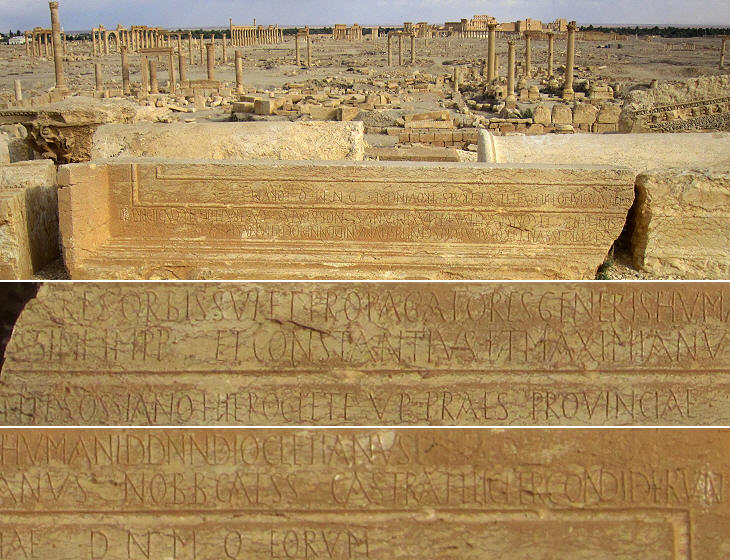

Palmyra enjoyed a large autonomy in the frame of the Roman Empire and Emperor Hadrian gave the city the status of free town, which granted ample latitude of authority to its magistrates. After the rebellion of Zenobia, however, Roman control over Palmyra became more stringent and Emperor Diocletian ordered the construction of a castrum, a permanent military town, on the site of Zenobia's palace. The standards of the garrison were placed on display in a large apse near the headquarters.

The Latin inscription celebrating the foundation of the camp by Sossianus Hierocles, Governor of Syria, is interesting because it mentions the names of all four Tetrarchs: Diocletian and Maximian (imperatores) and Constantius and Maximianus (Galerius) (caesares); the inscription however shows the greater role of Diocletian by mentioning him in the first line. The two imperatores were given the epithet of propagatores generis humani which indicates how far Diocletian had pushed his policy of deification of the living emperor.

With the exception of the Temple of Baal Shamin all the area to the north of the Colonnade between the Tetrapylon and the Funerary Temple was occupied by a vast residential quarter which included some rich houses with imposing porticoes; other residential quarters have been identified near the Temple of Bel, but they were of a smaller extension; an investigation of the area south of the Colonnade is currently being performed by a joint Syro-Italian team (external link).

Syria housed some of the earliest and most important Christian communities and it retains many early churches from those at Ezra, near the border with Jordan, to those in the Byzantine Dead Towns, near the border with Turkey. From this respect, Palmyra has little to show, with the exception of the Temple of Bel which was turned into a church and the remains of two small churches in the residential quarter.

Mark Twain in the Innocents Abroad mentioned ironically that the local guides attributed almost all the monuments of Rome to Michelangelo; had he visited Palmyra Twain would have noted the same approach with Zenobia replacing Michelangelo; the "Walls of Zenobia" were actually built at the time of Emperor Diocletian; the decision was part of a new military strategy which was developed after raids on major cities of the Empire such as Athens by tribes of Goths and which led to the construction of the walls of Rome. The walls of Palmyra incorporated the towers of a necropolis at the north-western end of the city. The walls were restored by Emperor Justinian in the VIth century.

The Arab Castle stands on a barren hill to the west of Palmyra and it appears in many spectacular views of the city. The current castle is actually a XVIIth century fortress which was built by a local emir who was trying to establish an autonomous kingdom in the region which was part of the Ottoman Empire; under the building archaeologists have found evidence of an ancient acropolis which was fortified in the XIIth century and eventually abandoned. Go to: Introduction Temple of Bel Colonnade Funerary Monuments Map of Syria with all the locations covered in this website     |