What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in June 2015. |

- Manisa - its Ancient Past - Manisa - its Ancient Past(bust of Ayse Hafsa Sultan and the mosque she built)

The view of Magnesia on approaching the town is the finest I have yet seen in Asia Minor. The steep ridge of Sipylus terminating abruptly at the left again reminded me of Sagalassus. Francis Vyvyan Jago Arundell - A Visit to the Seven Churches of Asia - 1826 Tomorrow (February 22nd, 1838) I leave Smyrna for Magnesia. I was to have started this morning, and the horses were brought to the door; but the wind from the north-east, in which direction we were to travel, was so high and so intensely cold that we could not face it. Ice covers every pool, and even the streams are frozen. (..) The town of Magnesia lies along the foot of a fine range of hills, backed by the almost perpendicular face of a rocky mountain (Mount Sipylus), whose top is now slightly capped with snow. Charles Fellows - Journal Written during an Excursion in Asia Minor in 1838

I had an inclination to see the inland situation of (A)Natolia before I left its coasts and therefore set out on the ninth of March for Magnesia which is 8 hours travelling from Smyrna. I set out at sun rise accompanied by a Drogman (interpreter), an Armenian servant and a guide. We were all well armed which is customary in this country and frequently necessary in the shortest journey. We took horses from the caravan which goes every Wednesday and Sunday from Smyrna to Magnesia. (..) I seized the opportunity to see what plants the spring had brought forth. Saffron (Crocus Sativus Linn.) was the first and the most remarkable I found. The Hyacinth (Hyacinthus Orientalis) and Star Flower (Ornithogalum) were the other spring flowers I found here. Fredrik Hasselquist - Voyages and Travels in the Levant in the Years 1749, 50, 51, 52. Translated into English in 1766. Hasselquist was a Swedish botanist and a scholar of Carolus Linnaeus. He travelled in the Levant to gather information about the natural history of the region.

Achilles then went back into the tent and took his place on the richly inlaid seat from which he had risen, by the wall that was at right angles to the one against which Priam was sitting. "Sir," he said, "your son is now laid upon his bier and is ransomed according to desire; you shall look upon him when you (take) him away at daybreak; for the present let us prepare our supper. Even lovely Niobe had to think about eating, though her twelve children - six daughters and six lusty sons - had been all slain in her house. Apollo killed the sons with arrows from his silver bow, to punish Niobe, and Diana slew the daughters, because Niobe had vaunted herself against Leto; she said Leto had borne two children only, whereas she had herself borne many - whereon the two killed the many. Nine days did they lie weltering, and there was none to bury them, for the son of Saturn turned the people into stone; but on the tenth day the gods in heaven themselves buried them, and Niobe then took food, being worn out with weeping. They say that somewhere among the rocks on the mountain pastures of Sipylus, where the nymphs live that haunt the river Achelous, there, they say, she lives in stone and still nurses the sorrows sent upon her by the hand of heaven. Therefore, noble sir, let us two now take food; you can weep for your dear son hereafter as you are bearing him back to Ilius - and many a tear will he cost you." Homer - The Iliad - Book XXIV - Translation by Samuel Butler

Manisa stands on the site of Magnesia ad Sipylum, so called to distinguish it from the Magnesia on the banks of the Meander (near Priene). It is mentioned by Strabo as being a free town under the Romans, and subject to earthquakes. It was one of the twelve cities of Asia that were thrown down by earthquakes in the reign of Tiberius. George Keppel - Narrative of a Journey across the Balcan in the Years 1829-1830 The Byzantine walls on the hills south of the town are the main evidence of Manisa's past, because the location of the Roman monuments has never been identified.

The Byzantine walls were built in different periods; the oldest ones are those in opus caementicium, a sort of concrete which has proved very solid and was faced with small bricks. Eventually other walls were built making use of materials taken from ancient buildings. See a page on Roman construction techniques.

Manisa is situated in the valley of the River Gediz (ancient Hermos) which is a natural passage between the Aegean Sea coast and the tableland. Its Archaeological Museum houses many interesting reliefs and statues found in ancient towns in the River Gediz valley, chiefly at Sardis.

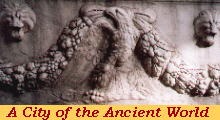

The common decorative features of the series to which our sarcophagus belongs are the repeated design of garlands of fruit or foliage. The festoons are bound by ribbons held up by animal heads or cupids standing on brackets or pedestals. The space above the garlands might be carved with rosettes or Medusa heads, and the pendant consists of a bunch of grapes. Anna Marguerite McCann - Roman Sarcophagi in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York - 1978. During the IInd/IIIrd century AD many sarcophagi were made by workshops in Asia Minor and then sold in other parts of the Roman Empire. Their manufacturing/marketing process is an early example of factory production (rather than made to order) system. Sarcophagi with festoons, because of the genericity of their decoration, had a wide market and constituted the commonest type of expensive sarcophagus of the time. You may wish to see similar sarcophagi found at Iasos and in Libya.

Small gravestones were usually made to order and their decoration had references to the age, sex and status of the dead. They often included inscriptions which shed light on the life of the deceased and on interesting aspects of society.

The image used as background for this page shows an ancient capital in Ulu Camii, one of the three Great Mosques of Manisa which are covered in page two. Clickable Map of Turkey showing all the locations covered in this website (opens in another window).     |