What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page revised in January 2011. |

- The Triumph of Life - The Triumph of Life

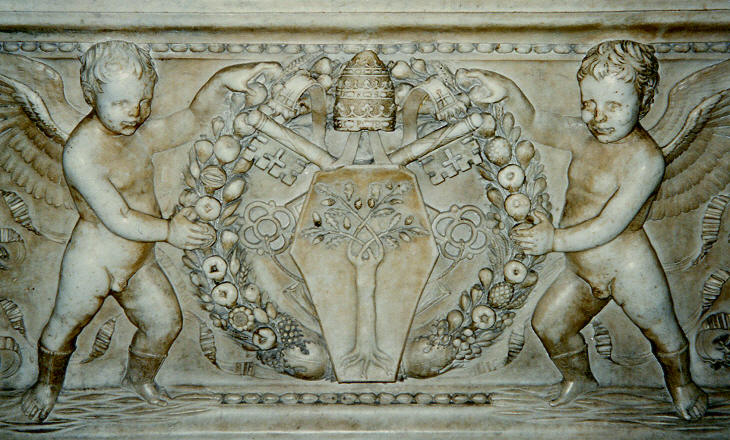

The Renaissance flourished in Rome later than in other Italian cities such as Florence and Venice; Pope Sixtus IV in view of the 1475 Jubilee Year promoted several initiatives which attracted many artists from other Italian regions; among them Andrea Bregno and Mino da Fiesole who were very talented bas-reliefs sculptors and who decorated Cappella Sistina and S. Maria del Popolo with some very elegant coats of arms of the pope and other members of his family. In the image above the coat of arms is placed in a wreath of fruit, a symbol of abundance and it is held by two angels; this "format" was introduced by Pope Paul II in a coat of arms in Palazzetto Venezia, a few years earlier.

During the annexation of Rome to Napoleon's Empire, the French troops garrisoned in Castel Sant'Angelo erased all the coats of arms of the popes on the exterior of the fortress, including that of Pope Alexander VI on its front; luckily they spared a well in one of the courtyards; although meant for a fortress, the well was finely decorated with the papal coat of arms and with other heraldic symbols of the pope (which a sharp eye can detect on the border of his uncle's - Pope Calixtus III - coat of arms at Ponte Milvio). The cow which appears in the coat of arms gave the name to an inn (Albergo della Vacca) near Campo dei Fiori which was owned by Vanozza Cattanei, the pope's mistress.

In some cases, rather than placing their coat of arms, the popes fostered a decoration based on their heraldic symbol; Pope Julius II was a member of the Della Rovere family; rovere indicates a particular species of oak (sessile or durmast oak) and the coat of arms of the pope (identical to that of Pope Sixtus IV, his uncle) showed an oak with reversed branches. When Pope Julius II promoted the completion of a large church to house Madonna della Quercia, a sacred image which was placed on an oak (It. quercia) in the outskirts of Viterbo, the fašade was decorated with a relief showing that tree which was at the same time a reference to the sacred image and to the heraldic symbol of the pope.

During the first two decades of the XVIth century Rome took the lead as the main Italian artistic centre; Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo and many other artists were called by the popes to design and decorate new churches and palaces; Donato Bramante designed a (lost) coat of arms of Pope Leo X which we know through an etching by Filippo Juvarra; the work of these great artists was supported by a number of skilled artisans who took care of ensuring that all the details were executed at a high standard. The coats of arms and the heraldic symbols of the popes became a recurring decorative motif.

The shape of the papal coat of arms was modified by Michelangelo when he designed that of Pope Paul III in Palazzo Farnese (you may wish to see it in an etching by Filippo Juvarra); the size of the keys and of the overall coat of arms became colossal and the heraldic symbol was no longer placed on a shield but on a more elaborate support which gave it a three-dimensional aspect. These gigantic coats of arms acquired a specific function in the overall design of palaces and churches and they were no longer a mere decoration.

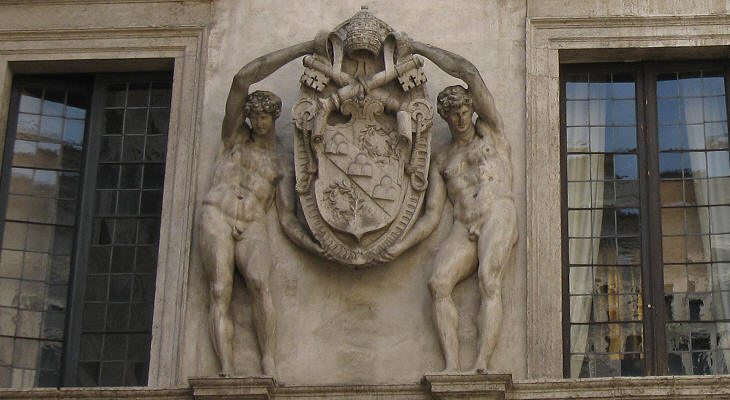

During the XVth and the XVIth century many classic statues were unearthed in the ruins of the ancient monuments; their nakedness impressed the artists of the Renaissance who started to compete with the ancient masters in portraying the naked human body; this led to replacing the angels which held the coats of arms of the popes with young men; Pope Julius III did not find inappropriate the decision of Cardinal Girolamo Capodiferro to have his coat of arms supported by two bodybuilders (see a page with other coats of arms of this pope). See a directory listing the Renaissance monuments of Rome.

SEE THESE OTHER PAGES (or return to the introductory page)

|