What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in March 2011. |

Leptis Magna: the Old Town Leptis Magna: the Old Town(Detail of a mosaic from Leptis Magna in the Museum of Tripoli) Similar to Oea and Sabratha, Leptis (aka Lepcis) was founded by the Phoenicians to support their trade routes along the coast of northern Africa. After the fall of Carthage in 146 BC at the end of the Third Punic War, the region of Leptis was included in the Kingdom of Numidia until 105 BC when the Romans absorbed it into the province of Africa. The appellation Magna (Great) was added to distinguish Leptis from another town by the same name, Leptis Parva (Small) which was located in today's Tunisia.

During the civil war between Caesar and Pompey, Leptis supported the latter, but its development did not suffer in a significant manner by its wrong choice: it was punished by having to provide Rome with a special delivery of olive oil. During the Ist century BC new quarters were added to the old town; they were designed according to traditional Roman layouts.

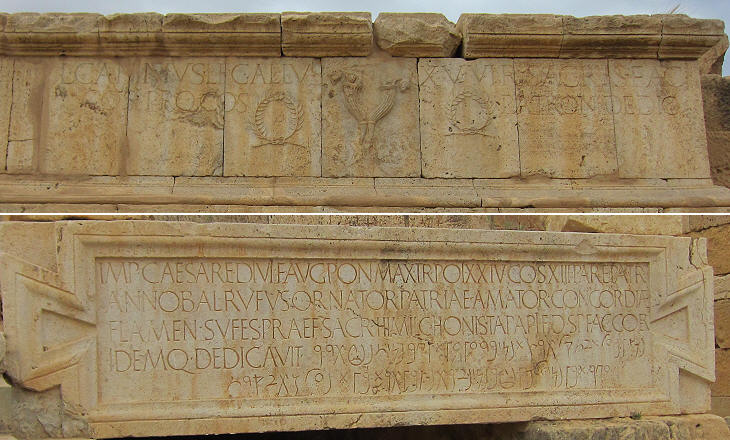

The Forum was designed at the time of Emperor Augustus on the former centre of the Carthaginian town; it was located very near the sea front and it was embellished by several small temples and decorated with gigantic statues of the emperors (now at the Museum of Tripoli); it is known as the Old Forum, because at the beginning of the IIIrd century AD Emperor Septimius Severus, who was born in Leptis, built a new forum which is discussed in page two.

The buildings of the forum were in part modified or restored during the reign of Augustus' successors; the presence of columns of grey granite from Egypt and of cipollino from Greece are an indication of Leptis' wealth; the improvements were made by Roman governors of the town or by rich local merchants.

The wealth of Leptis was based on extensive plantations of olive groves which surrounded the town; the yearly tax the town had to pay to Rome was levied in olive oil pounds; in return its inhabitants enjoyed a certain degree of freedom in local administration and appointed their suffetes, traditional Phoenician magistrates (Hannibal was a suffete of Carthage); often the names of the inhabitants were a mixture of Roman and Punic elements: Annobal Tapapius Rufus was a very wealthy merchant who financed the construction of the marketplace in 8 BC.

According to some historians the Latin word macellum, which means the market where fish and meat are sold, derived from a Punic word meaning the place where you eat; stalls were arranged along a circle or an octagon at the centre of which there was a basin where fish/meat and the knives employed for cutting them were washed. Expensive materials were involved in the construction of the marketplace and its buildings were accurately designed.

A miniature triumphal arch shows the ships which carried olive oil to Rome; that to the left has large sails and is very similar to ships which are depicted in a mosaic at Ostia, the harbour of Rome; that to the right shows a galley propelled by oars. Aediles were Roman magistrates in charge, among other duties, of ensuring the correctness of transactions at marketplaces; archaeologists have often found sets of standard measurements placed by aediles to fulfil this objective; the set of measurements shown above was probably used to check the length of fish (you may wish to see a similar set at Dion in Greece).

Annobal Tapapius Rufus, after having financed the construction of the marketplace paid for that of a large theatre; it is one of the first examples of a theatre which was not entirely excavated from a hill as the upper part of the stands is supported by masonry; it was completed a few years after Teatro di Marcello in Rome and it is just slightly smaller than the theatre of Sabratha (which was built at a much later time).

In his long dedicatory inscription Annobal Tapapius Rufus calls himself amator concordiae (lover of concord) and another similar inscription is decorated by two shaking hands; clearly the rich merchant was a keen supporter of friendly relations with Rome; new roads which linked Leptis to the interior were built by the Romans in the Ist century AD, thus increasing the area of the olive groves, to the detriment of the nomads, whose land was confiscated.

Iddibal, another member of the Tapapius family, completed the work and the political mission of Annobal, by building a large temple behind the theatre and by dedicating it to the first Roman emperors; relations between Rome and Leptis became so strong that many important inhabitants of the town were given Roman citizenship, which allowed them to pursue a political career and to be assigned to positions in the army.

At the time of Emperor Nero a quarry near the town was turned into a large amphitheatre; in the introductory page you can see an extremely fine mosaic portraying the gladiatorial fights which took place in this amphitheatre which was enlarged by Emperor Septimius Severus.

Chariot races took place between the amphitheatre and the sea shore; the circus was built at the time of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, but the site was most likely already used for races.

The amphitheatre and the circus formed a unique compound and the audience could easily move from one to the other; it is thought that performances were planned in order to make use of both facilities; in the centuries of abandonment which followed the decline of Leptis, the circus was plundered not just of its statues and decorations, but of the very stones by which it was built; the proximity to the sea made it easy to load them on ships.

In spring 128 AD Emperor Hadrian visited the province of Africa, of which Leptis was one of the key cities; his arrival coincided with a period of rain which ended a long drought; at the end of each visit the emperor used to make recommendations and he followed them up; this explains the large number of facilities throughout the Roman Empire which are named after him from Hadrian's Wall in Britain to the baths of Leptis Magna which were completed in 137, the year of the emperor's death.

The design of the baths is symmetrical along a north-south axis; halls and facilities are duplicated, with the only exception being that of the natatio; archaeologists believe that men and women could bathe separately at the same time with just the natatio being reserved to one sex.

A specially built aqueduct provided the baths with that ample supply of water which they required; several columns of grey granite and of cipollino were imported together with white marble for the capitals of the columns.

The baths were decorated with different kinds of marbles and with many statues, some of which are now displayed at the Museum of Tripoli; one of them portrays Antinous, Hadrian's young lover who accompanied the emperor in his journey to Leptis Magna and who drowned in the Nile two years later.

The baths were equipped with two large toilet rooms; their design is very similar to other such facilities which can be seen at Sabratha, Ostia and many other locations in the Roman Empire.

Serapis was a god with features deriving from Egyptian Osiris and Greek Zeus; he became very popular in the IInd century AD and Roman emperors such as Hadrian promoted his cult as they believed it would have strengthened the unity of the empire. The Temple to Serapis at Leptis was built at the time of Emperor Marcus Aurelius and it was decorated with columns of a rare marble having blue veins. The image used as background for this page shows a detail of a mosaic in the Museum of Leptis Magna. Go to Leptis Magna - the Age of Septimius Severus or to: Introductory page Oea (Tripoli) Sabratha SEE THESE OTHER EXHIBITIONS (for a full list see my detailed index).    |