What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. |

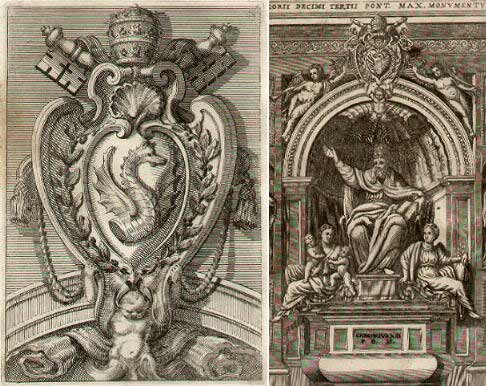

Gregory XIII Gregory XIII(dragon in the Monument to Maria Eleonora Boncompagni Ludovisi in S. Maria del Popolo) The Dragon Cardinal Ugo Boncompagni was elected pope on May 13, 1572 after a one-day conclave. His election was supported by Spain where Cardinal Boncompagni had been nuncio (ambassador) for several years. His coat of arms shows a dragon with a truncated tail (the evil part of this imaginary animal). This is not always evident in some coats of arms or in statues of the dragon. He was buried in St Peter's near the part of the church (Cappella Gregoriana) erected under his pontificate and the monument was topped by a coat of arms, which Filippo Juvarra included in his 1711 book on the coats of arms of the popes (in the drawing the dragon is looking to the right, while in the actual monument it is looking to the left). The coat of arms was lost a few years later when a new monument to the pope was designed by Camillo Rusconi (the dragon in the background of the page is part of this new monument). The dragon can also be seen in the coats of arms of the families Borghese and Del Drago.

Outside Rome Gregory XIII was born in Bologna in 1502 and he was always proud of his birthplace. He used to add Bononiensis to his name. In return Bologna in 1580 erected to the pope a gigantic bronze statue (by Alessandro Menganti) in the front of Palazzo Comunale. The coat of arms was not spared by the effects of the French Revolution in Italy. The coat of arms of the pope inside the palace was deprived of the papal attributes.

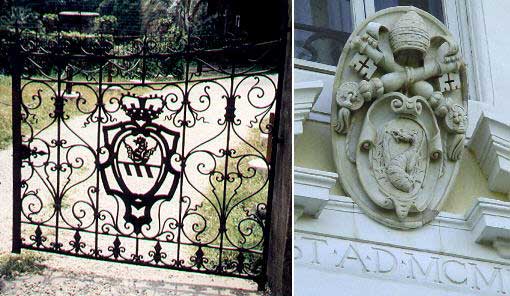

For the Holy Year called in 1575 Gregory XIII enlarged the port of Civitavecchia which allowed the pilgrims from France and Spain easy access to Rome by sea. The coat of arms celebrating the event was severely damaged when Civitavecchia was bombed during World War II (next to the coat of arms an inscription in honour of Pope Urban VIII). Coats of arms of Gregory XIII can be found in many towns of the papal state (see the gate in his honour in Visso).

Near Rome the coats of arms of Gregory XIII had better luck. In 1681 the Boncompagni inherited the possessions of the Ludovisi another family from Bologna (Pope Gregory XV) and the coat of arms was modified to include a reference to the heraldic symbol of the Ludovisi. The Ludovisi had a large Villa near Porta Pinciana in Rome and another Villa near Albano in the Castelli Romani. A coat of arms of Gregory XIII is also in Villa Taverna, the residence of the Ambassador of the United States near Monte Porzio Catone in the Castelli Romani (by courtesy of Mr Tom Wukitsch).

In Rome Gregory XIII was confronted with the challenge posed by the other Christian religions in northern and eastern Europe. He founded Collegio Germanico, Collegio Greco (near S. Atanasio) and Collegio Inglese (near S. Tommaso di Canterbury). He is considered the second founder of Collegio Romano (the University was named after him). He started the enlargement of Archiginnasio della Sapienza. He was a lawyer and promoted new legislation also in urban development matters. Some of the streets that were completed by his successor Sixtus V were initially designed under Gregory XIII (Via Gregoriana is named after him). His main initiative in Rome had bad luck: the new bridge he built near S. Maria in Cosmedin lasted only a few years and it is known as Ponte Rotto (broken bridge). He brought order to the relationships between the papacy and the formally surviving political bodies of the City of Rome. The tower of Palazzo Senatorio the symbol of communal life was erected under his pontificate and he was celebrated in a statue in the main hall of the building (the statue was moved in the late XIXth century to nearby S. Maria in Aracoeli). The statue shows on the side of the seated pope a dragon (with the appearance of a faithful dog): this idea was copied in similar statues showing Sistus V (with a lion instead of the dragon) and Paul V (with an eagle added to the dragon).

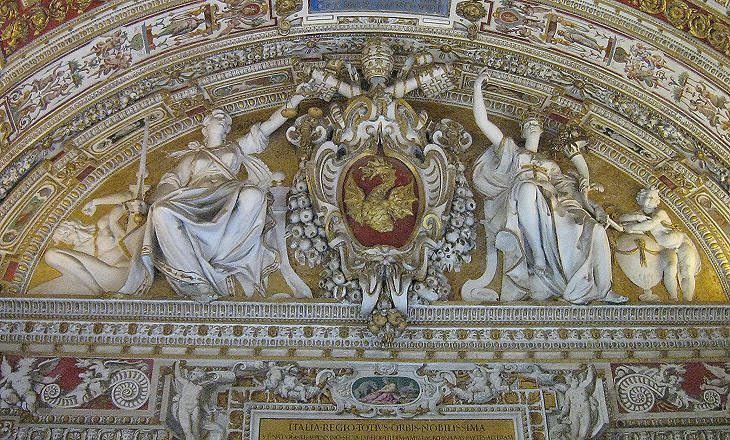

Gregory XIII was also supportive of the Church taking the lead in scientific matters. This statement is in contrast with the general view which sees the Church in a rearguard position in these matters, but in the late XVIth century and in the first part of the next century, at least until Galileo in 1633 was forced to abjure his astronomical theories, Rome was home to many scientists. An example of the progress made in topography is the Gallery of Maps in the Vatican Palace: the gallery is frescoed with detailed maps of Italy, including views of the main ports. The ceiling is full of stuccoes and paintings and the entrances to the gallery are decorated with the coats of arms of Gregory XIII.

Gregory XIII completed the first part of St Peter's (its NE corner), which is called after him Cappella Gregoriana, although it is not a chapel, but rather a part of the transept (in the layout of the basilica following its transformation into a Latin cross church). It was initially designed by Michelangelo and then completed by Vignola (who designed its dome) and Giacomo Della Porta. Gregory XIII had the final say in its decoration and his decision to have mosaics rather than frescoes had an influence on the overall decoration of St Peter's. A large circular mosaic with his coat of arms is at the center of the chapel (it was copied by the popes who built the other parts of St Peter's).

Gregory XIII was buried in St Peter's next to the chapel in a monument which was replaced by a new one in 1715-23. One of the purposes of this new monument was to celebrate the Reform of the Calendar, by which in 1582 Gregory XIII endorsed the recommendations of a group of scientists and established new rules for the leap year. The ancient civilizations had calendars based on the moon cycle, with various rules to relate it to the sun cycle (succession of years with 12 or 13 months). The Julian calendar named after Julius Caesar introduced a solar calendar of 365 days, every fourth year having 366 days. In the XVIth century a discrepancy between the dates of the solstices and the actual solstices became evident and research indicated that the solar year was slightly shorter than 365 days and 6 hours (as assumed in the Julian Calendar). The Reform of the Calendar introduced by Gregory XIII (hence Gregorian Calendar) cancelled the leap years at the end of the century (but not in those like 2000 which are divisible by 4). The Reform abolished the days between October 4 and October 15, 1582 to readjust the calendar for the past discrepancies. The Reform was introduced in the Catholic countries, but only in the XVIIIth century in England and in the XXth century in Russia (that's why the October Revolution occurred in November 1917). The Orthodox Church has never endorsed the Reform of the Calendar introduced by Gregory XIII and for this reason the Orthodox Christmas and Easter days fall some days later. VISIT THESE OTHER EXHIBITIONS (for a full list see my Detailed Index)

|