What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. |

Change and tradition in the papal transition to  Part one Foreword This page contains minor remarks and curiosities related to the events and ceremonies associated with the death of Pope John Paul II on April 2, 2005. For a page covering aspects of the appointment of his successor click here. The Prophecies of Malachy The Irish hermit Maelmhaedhoc O'Morgair (1094-1148) (his name was Latinized as Malachy) is the assumed author of a list of attributes of the future popes, starting from Celestinus II (1143-44). The document was most likely written in the late XVIth century; each pope is identified by a couple of words. For the successor to John Paul II, the prophecy states De Gloria Olivae (Glory of the Olive). Certainly if these words had been written for the successor of Pope Urban VIII, they would have been taken as an indication in favour of Cardinal Giovan Battista Pamphilj, because his coat of arms showed a dove bearing an olive branch (the small image at the top of the page shows a Pamphilj dove in S. Agostino). Because the olive is a symbol of peace, the general thought is that the prophecy is a good omen and that the new pontificate will mark a period of peace. A disturbing aspect of these prophecies is that the list is coming to an end: after De Gloria Olivae there is only one prophecy left: Petrus Romanus and the reference to the first pope is clearly meant to indicate the end of a cycle.

Names of the Popes The first pope who changed his name at the moment of appointment was John II in 535. His original name was Mercurius or Mercurialis and it obviously had a too clear reference to the pagan god. In 955 another John (XII) changed his name for similar reasons: his original name was Octavian and he thought that bearing the name of the great Roman Emperor Augustus did not suit his papal role. Yet another John (XIV) in 983 abandoned his original name: on this occasion his name, Petrus, was too demanding. Soon after the change of name became the rule: in 996 the Emperor Otto III imposed on the Romans the election of his 24 years old cousin Brunone; the young man, the first German pope (Gregory V), changed his name to that of a great Roman pope to signify he was now a Roman citizen and his foreign origin did not matter any more. After him, almost all the following popes adopted a new name. Nec nomen mutabo, nec mores, Marcellus fui, Marcellus ero ("Neither name nor behaviour I will change: I was Marcellus, I will be Marcellus"). In 1555 Cardinal Marcello Cervini broke the tradition and retained his name. This deviation remained isolated, maybe because poor Pope Marcellus II passed away just 27 days after his election. Very often the new pope chooses the name of his predecessor or of the pope who appointed him cardinal. Thus everybody was caught by surprise in 1958 when Cardinal Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli chose to be called John XXIII, a name which had not been selected for more than 500 years, partly because there was uncertainty whether Cardinal Baldassarre Cossa, elected in 1410 with the name of John XXIII by a conclave in Bologna should be regarded as a pope or an anti-pope. But Cardinal Roncalli by interrupting the series of Pius who had ruled the Church for nearly two centuries, wanted to send an early indication of his desire for innovation.

Nationality of the Popes

In the early centuries of Christianity some of the Bishops of Rome were chosen among members of the Syrian and Greek communities, because in these countries the new faith had many more followers than in Italy: this trend continued till the VIIIth century (when out of 12 popes 6 were of Greek or Syrian origin) for a different reason: Rome had become a remote province of the Eastern Roman Empire and the appointment of the pope required the approval of the Emperor, located in Constantinople. The Byzantine influence in Italy was replaced by that of Charlemagne. In the XIth century 8 popes were of German or French origin. In 1305 Philip the Fair, King of France imposed the election of the French Bertrand de Got (Clement V) who never set foot in Rome and established his residence in France, eventually in Avignon; the next 6 popes were all French. The return of the Papal See to Rome was followed by a period of great confusion with two or even three popes at the same time. In 1417 a Council held in the German town of Constance led to the appointment of Martin V and since then all the popes have been of Italian origin with the following exceptions: Calixtus III - Alfonso Borja (Borgia) - 1455-1458 - Spanish Alexander VI - Rodrigo Borgia - 1492-1503 - Spanish Adrian VI - Adriaan Florisze - 1522-1523 - Dutch and obviously John Paul II - Karol Wojtyla - 1978-2005 - Polish. Many popes came from the other Italian States, in particular from Tuscany. From Slippers to Shoes

Pope John XXIII drastically reduced the pomp which previously marked papal appearances including those related to the body of the deceased pope (you can read a description of that pomp by clicking here). A further step in this direction was made by showing the body of Pope John Paul II wearing shoes rather than the traditional red slippers. The slippers were a reminder of the traditional act of devotion which consisted of kissing the pope's slipper, which was embroidered with a golden cross. The statues portraying the pope sitting on his throne always show a slipper protruding from the gown (this is very evident in the bronze late XVIth century of Sixtus V shown above).

Novem Dies In 1274 the Council of Lyon at the request of Pope Gregory X issued the constitution Ubi Periculum (a decree) setting the rules for the election of the pope, which to a great extent are still followed. The need for such a decision came from the incredible delay before the cardinals had elected the last pope: it had taken them three years to make their choice: they had met in the Papal Palace of Viterbo so many times that in the end the inhabitants of the town, to force them to stop their inconclusive bickering, walled up the gates and windows of the palace, opened the roof, and supplied the cardinals with just bread and water. One of the rules provided for an interval between the funeral of the pope and the beginning of the conclave of ten days. Later on in the XIVth century it was established that the deceased pope would be mourned for nine days after his funeral, during which time his body was honoured and suffrage masses were said each day. As a matter of fact this practice was copied from the mourning ceremonial of the Byzantine emperors.

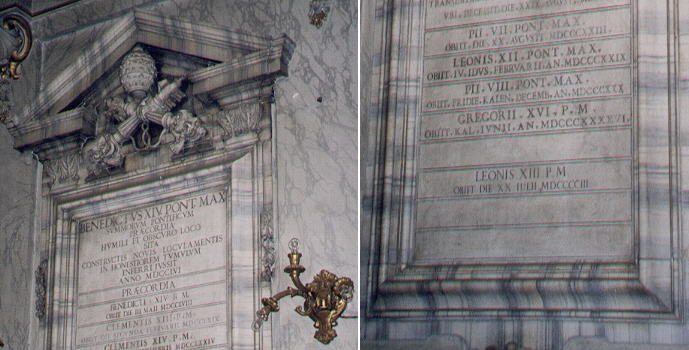

The long interval between the death of the pope and his burial led to some form of embalming of his body: the inner organs (liver, heart, lungs) were removed to avoid their deterioration. So while the bodies of the popes are buried in St. Peter's or in other important churches (see my page on the Monuments to the Popes), the inner organs (in Latin Praecordia) are kept in a small church at the foot of Palazzo del Quirinale. This practice went on until 1903 (death of Pope Leo XIII). In 1914 Pope Pius X expressly prohibited it in his burial and successive popes have supported his decision. Since the end of the XVIth century the popes set their residence in this palace and the funeral consisted in the transfer of the body to St. Peter's where it was laid on an elaborated catafalque. Charles de Brosses described the catafalque erected in honour of Pope Clement XII in 1740 with these words: The catafalque in St. Peter's is magnificent and of very good taste, decorated with statues and medallions (round reliefs), inscriptions and paintings, showing the main events of the pontificate and the monuments erected by the pope; it is hard to believe that such a catafalque, which for its dimensions is actually a building, could be erected in such a short time. In this case the catafalque had been designed by Ferdinando Fuga the preferred architect of the pope and it was assembled just in a few days because all its components had been already prepared well ahead under the direct supervision of the pope himself. In 1622 the catafalque of Pope Paul V was decorated with 16 statues and 20 angels some of them sculpted by the then very young Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The great architect designed in 1669 the catafalque for Pope Clement IX, while Giovanni Antonio De Rossi designed in 1676 the catafalque for Pope Clement X.

John Paul II passed away after having had all reasonable medical care, assisted by loyal and faithful doctors and by a group of nuns, whom he regarded as his "family". The last days of other popes were more difficult. Pope Pius XII had offered of himself a very different image than that of Pope John Paul II: either because of his shyness or because he believed it was appropriate to his role, he rarely appeared in person and when he did so it was with all the pomp of the past centuries. It was even more unfortunate that some pictures of the dying pope were sold to a magazine by his disloyal doctor who, in 1958, had taken these with a hidden camera. Pope Pius IX had reigned for 32 years, proving false the prophecy that no pope could stay in office for more than 25 years, which was the assumed period spent by St. Peter in Rome. But his long pontificate had been very controversial and his repression of the Italian patriots, which included the death penalty for those accused of conspiracy, was not forgotten. He passed away in 1878 and in his will he expressed the desire to be buried in the Basilica di S. Lorenzo fuori le Mura, but the political situation (the Holy See did not recognize the Italian annexation of Rome) suggested delaying the transfer of the body. A few years later, with the agreement of the Italian Government, arrangements were made to move the body at night by just a simple carriage and in a very secret way: nevertheless the news leaked and a group of anticlericals managed to block the carriage on Ponte Sant'Angelo and the body of the pope very narrowly escaped being thrown in the Tiber. It reached its destination and it was eventually placed in a lavishly decorated chapel in the oldest part of the Basilica. Pope Pius VI passed away in 1799 in the French town of Valence, where Napoleon had confined him and only in 1802 the emperor allowed the transfer of his body to Rome. The death of his predecessor Pope Clement XIV in 1774 is generally attributed to poisoning by the Jesuits, whose order he had abolished the previous year at the request of kings and emperors, envious of the role and influence achieved by the Order in their countries.

Charles de Brosses wrote in 1740 with some disappointment: They told me that usually at the death of a pope, a mob moves from Trastevere to Piazza di Spagna in an outbreak of lawlessness. I spent all day at my window hoping to see the show of such a tumult: unfortunately nothing happened... In the previous centuries very often the death of the pope meant a temporary collapse of the institutions: in 1559 the riots at the death of Pope Paul IV led to the destruction of all the symbols of his pontificate and not a single coat of arms of this pope was spared. Pasquino

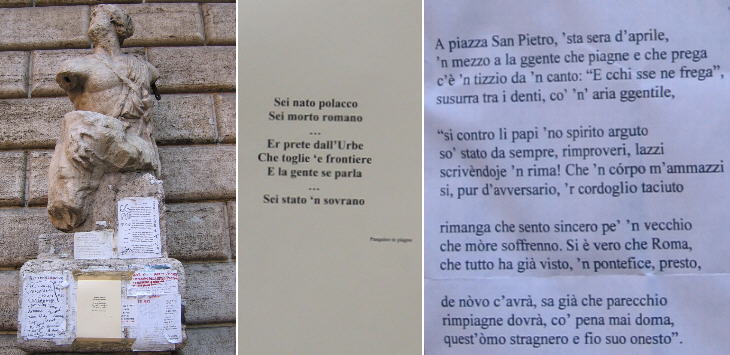

Pasquino the only surviving talking statue of Rome paid tribute to Pope John Paul II: "You were born a Pole; you passed away a Roman. (you were) the priest (who) from Rome took away the borders and let people speak. You have been a sovereign." And in the fine print: "Pasquino mourns you". The sonnet conveys the same message especially in the last verses (Rome knows she will miss... this foreign man and her honest son). But Pasquino was not so gentle with other popes: Benedict XIII - 1730 - Più che amator di santi/protettor di briganti (more than lover of saints/(he was a) protector of brigands) Clement XIV - 1776 - Venne da volpe, mendace;/regnò da lupo, impostore;/morì da cane, empio. (He came as a fox, a liar;/He ruled as a wolf, a swindler;/He died as a dog, impiously.). Gregory XIV - 1846 - Più che di Cristo, adorator di Bacco (More than Christ, he worshipped Bacchus). The image used as a background for this page is a detail of a XVIIth century print portraying the Monument to Pope Martin V in S. Giovanni in Laterano. SEE THESE OTHER EXHIBITIONS (for a full list see my Detailed Index) |