What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in December 2014. |

- Roman Pola (Pula) - page two - Roman Pola (Pula) - page two(Longobard weapons at Museo Archeologico di Cividale) You may wish to read an introduction to this section or page one first.

The Amphitheatre is in many ways the most interesting example of that class of building which has come down to us from the Roman world. (..) Dr. Pietro Kandler (an archaeologist from Triest) calculates that if the upper gallery with its wooden floor were reserved for a promenade and not seated the amphitheatre would have accommodated 21,000 spectators. This enormous number is of course quite disproportionate to the population even of Roman Pola, and prove that the shows were intended not only for the city, but for the province. Sir Thomas Graham Jackson - Dalmatia, the Quarnero and Istria - 1887 Sir Thomas Graham Jackson (1835-1924) was one of the leading architects of his time. He visited Pola in 1885. Other excerpts of his book can be read in a section covering Diocletian's Dalmatia. The Amphitheatre is the best known monument of Pola and it was studied by many Renaissance artists, including Michelangelo. One cannot escape comparing it with the Colosseo or the Amphitheatre of Thysdrus (today's El-Djem in Tunisia).

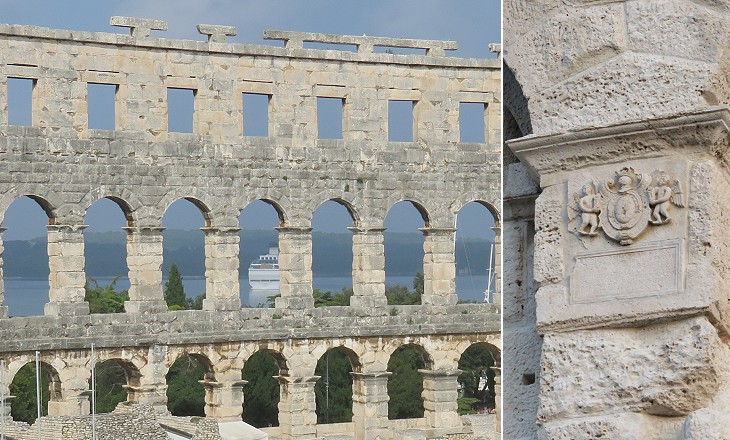

Like the theatre (see below in this page) it was built on the slope of a hill, and material was economized by making the natural formation of the ground serve instead of a substructure for the ascending tiers of seats on the landward side. Thus, while there are four orders or stories on the side next the sea, there are but two on that towards the land, the two lower stories being absorbed by the rising ground. (..) The most curious features of this amphitheatre are the stone balustrading round the top of the wall, below which are perfectly preserved the sockets and channels for the masts of the velum or awning, and the four rectangular projections - one can hardly call them towers - which break the regularity of the exterior ellipse. T. G. Jackson

These projections are extremely ornamental, but can hardly have been added merely for appearance, and their object has never been satisfactorily explained. If they contained staircases, for which some evidence exists, they must have been so cramped as to have been of no use to the public, though they may have served for the attendants who had the management of the awning. T. G. Jackson The purpose of the towers is still unexplained today. The Romans were always very careful in preventing a disorderly exit from a theatre/amphitheatre which could cause a stampede. They built vomitoria, large vaulted passages, to ensure this did not occur, so, as Jackson noted, it is unlikely the towers housed staircases for the public.

The tiers of stone seats in the interior, the vaulted corridors and radiating chambers that supported them, and the podium or enclosure of the arena have now entirely disappeared, with the exception of such slight fragments as serve to shew that they once did exist, and that they were not all constructed of wood as might at the first moment have been imagined. All that now remains is the exterior of the building, a vast elliptical wall pierced with arches in tier above tier, and enclosing a green meadow. (..) As to the age of this amphitheatre there are several opinions. (..) Dr. Kandler says it is certainly a building of the first century after Christ, probably built by Vespasian, the Flavian family having possessions in Istria. T. G. Jackson Today the prevailing opinion is that the amphitheatre was built at the time of Emperor Augustus and then enlarged by Vespasian.

The disappearance of the interior masonry without injury to the outer circuit is explained by the entire separation that must have existed between the two, even when the building was perfect. The gallery or corridor that ran all round the outer circuit on each floor was not vaulted; no arches of masonry spanned the passage between the outer ellipse and that next within it; but on examination it will be found that there are holes in the outer wall at the floor levels, which received massive joists of timber for a wooden floor; and at one level there is a set-off in the wall as if stone slabs had been laid across. The decay of these slight floors would leave the outer wall detached from the whole interior construction, and while they respected the architectural beauty of the outer ring, the Polesi felt no scruple about demolishing the interior structure and using the materials in their town walls and private houses. (..) Excavation has revealed in the centre of the arena a long and wide trench (today it houses a small underground museum), some ten or twelve feet in depth and formed with sides of regular masonry, in which were two rows of stone pillars, which probably carried a wooden floor level with the rest of the arena. T. G. Jackson

The amphitheatre was built outside the walls of the town on a hill overlooking the harbour. In the late XVIth century the Venetians debated whether the building could not impair the defence of the town by providing Ottoman assailants with a sheltered site where they could easily set their camp and place their guns. Senator Gabriele Emo successfully opposed the destruction of the amphitheatre and, as a sign of gratitude, the citizens of Pola placed a celebratory inscription and his coat of arms on one of the towers. By mere coincidence in that same period the Colosseo was close to being pulled down by Pope Sixtus V who wanted to open a new street across it. The project was eventually abandoned.

Of the theatre popularly known as "Zaro", which stood outside and to the west of the town walls, nothing unfortunately remains, but the excavation hollowed in the rocky hill-side for the seats of the auditorium. Although it had been injured by a hurricane, the building remained in a tolerably perfect state till 1636; but in that year it was destroyed, and the stones were used by Antony de Ville, a French engineer, to build the fortress on the Capitol. T. G. Jackson The fortress was built on the top of the hill on the site of the (lost) Roman Capitolium, a temple to Jupiter, Juno and Minerva (you may wish to see the impressive Capitolium of Sufetula in Tunisia). Pola had a second theatre inside the walls, right below the fortress, which is shown in this page. Jackson might have confused the two when he made reference to the fortress being built with the stones of the theatre.

Serlio, who saw the theatre in the first half of the sixteenth century, has published a plan, sections, and elevations of it which give an idea of its magnificence (it opens in another window). He says it was of the Corinthian order, very richly ornamented with sculpture di "pietra viva"(carved into the stone), and that the scene was handsomely designed with columns above columns. The inside was much ruined even then, but the outside was so well preserved that he was able to make measured drawings of it. He mentions the economical ingenuity with which the architect had made use of the fall of the ground to save the substructure of the auditorium.T. G. Jackson Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554) is best known for his treatise on architecture and for a type of window named after him.

A large mosaic was unearthed during the construction of a modern building on the site of one damaged by WWII bombing. It is rectangular, fairly large (12x6m/40x20ft) and with no signs of walls dividing it. The design however shows a section with mainly hexagonal geometric motifs and another one with nine small square panels, as if the two sections had different uses.

The mosaic is dated IIIrd century AD most likely because of the panel which portrays the Punishment of Dirce. A gigantic statue (it opens in another window) depicting the same event embellished the baths built by Emperor Caracalla in 212-217 in Rome and it might have been "copied" by the author of the mosaic. The statue was found in 1545 and it was moved to Palazzo Farnese, hence it is known as the Farnese Bull. It is now in the Archaeological Museum of Naples. Antiope, a widow, was brought to Thebes by Lycus, her uncle. After giving birth in a wayside thicket to the twins Amphion and Zethus, whom Lycus at once exposed on Mount Cithaeron, she was cruelly ill-treated for many years by her aunt Dirce. At last, she contrived to escape from the prison in which she was immured, and fled to the hut where Amphion and Zethus, whom a passing cattleman had rescued, were now living. But they mistook Antiope for a runaway slave, and refused to shelter her. Dirce then came rushing up in a Bacchic frenzy, seized hold of Antiope, and dragged her away. After having been enlightened by the cattleman about who the running woman was the twins at once went in pursuit, rescued Antiope, and tied Dirce by the hair to the horns of a white bull, which made short work of her. Robert Graves - The Greek Myths - 1955

Dante made reference to a Roman necropolis near Pola having open sarcophagi. The location of the necropolis is unknown, but tombs were built outside the town in line with the Roman law. An octagonal mausoleum was recently found when enlarging the modern road along the walls. Although there is no evidence about it, one cannot fail to think it might have housed the body of Crispus. Hither was brought under a strong escort Crispus, the eldest son of Constantine the Great, and here in 326 he perished by a death as mysterious as the charges which had excited the jealousy of his father, and which were proved too late to be groundless. T. G. Jackson According to tradition Fausta, second wife of Emperor Constantine told her husband that Crispus, her stepson, had tried to seduce her (a story which recalls that of Hippolytus and Phaedra). Shortly after the death of Crispus, Constantine had Fausta killed by a (too) hot bath. Christianity has long claimed Constantine as one of its own. For the Greek Orthodox Church he is a saint and there is no lack of paintings and statues celebrating the emperor in the churches and palaces of Rome. The fact that he killed his second wife, his eldest son, his father-in-law and two of his brothers-in-law is regarded as a venial sin.

S. Maria in Canneto. No greater loss has befallen Pola, except perhaps that of the theatre, than that of the famous abbey church of S. Maria in Canneto, built by St. Maximian, the archbishop of Ravenna under whom so many buildings were erected in that city during the reign of Justinian. S. Maria in Canneto was consecrated in 546. It was a basilican church with a nave and aisles, the aisles being raised two steps above the nave. The nave ended with an apse, but the aisles instead of having apses terminated each in a circular chamber, of which Dr. Kandler saw the ruins. Two chapels in the form of a Greek cross stood right and left of the eastern end, one of which remains in the garden of a modern house and is still used as a church. It is quite plain. (..) The rest of this magnificent basilica, with its marble columns, mosaic pavements and Byzantine sculpture, has entirely disappeared, and the very site is covered with houses, gardens and workmen's yards. Its ruin began with the Genoese invasions in the fourteenth century; in the next century its marbles and bronzes were carried to Venice for the adornment of the churches there, and there is documentary evidence that at a still later date, in 1545, Sansovino was sent by the Senate to take away the marble columns of S. Maria Formosa (di Canneto) and bring them to Venice. (..) Its spoliation however was not yet complete, for in 1605 the Venetians transported hence the four magnificent columns of oriental alabaster that now stand against the apse wall of St. Mark's behind the high altar, which are well known to modern travellers from the trick of the "custodi", who strike a match behind them to shew their transparency, and unblushingly aver that they belonged to the temple of Solomon at Jerusalem. T. G. Jackson In Canneto, the name by which the Basilica was referred to, indicates that the area where it stood became marshy (it is very near the sea). Most likely this was the cause of its abandonment and decay. The design of the remaining chapel strongly resembles the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia at Ravenna. The history of Pola after the fall of the Western Roman Empire (476) is linked to that of Ravenna. It was conquered by the Ostrogoths in 493 and by the Byzantines in 538. It became part of the Exarchate of Ravenna and its harbour housed the Byzantine fleet. The medieval and Venetian monuments of the town will be covered in a separate page. Return to Roman Pola - page one: The Gates and the Forum or see its churches or its Venetian monuments or move to: Introductory page Roman Aquileia - Main Monuments Roman Aquileia - Tombs and Mosaics Early Christian Aquileia Medieval Aquileia Chioggia: Living on the Lagoon Chioggia: Churches Chioggia: Other Monuments Roman and Medieval Cividale del Friuli Venetian Cividale del Friuli Grado Palmanova Roman and Byzantine Parenzo (Porec) Medieval and Venetian Parenzo (Porec) Pomposa Roman Ravenna Ostrogothic Ravenna Byzantine Ravenna: S. Apollinare in Classe Byzantine Ravenna: S. Vitale Byzantine Ravenna: Other Monuments Medieval Ravenna Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Walls and Gates Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Churches Venetian and Papal Ravenna: Other Monuments Rovigno (Rovinj) Roman and Medieval Trieste Modern Trieste     |