What's New! Detailed Sitemap All images © by Roberto Piperno, owner of the domain. Write to romapip@quipo.it. Text edited by Rosamie Moore. Page added in July 2011. |

- Palmyra - Introduction - Palmyra - Introduction

In 1753 the publication of The Ruins of Palmyra, otherwise Tedmor, in the Desart by Robert Wood revealed the existence of imposing ruins of that ancient city to the European public; until then Palmyra was known only through references included by historians in their books. Wood visited Palmyra in the course of a voyage he undertook with two gentlemen whose curiosity had carried them more than once to the continent, particularly to Italy. They thought that a voyage, properly conducted, to the most remarkable places of antiquity, on the coast of the Mediterranean, might produce amusement and improvement to themselves, as well as some advantage to the publick, as he stated in the preface to his book.

The three English travellers agreed that a fourth person in Italy, whose abilities as an architect and draftsman we were acquainted with, would be absolutely necessary. We accordingly wrote to him (Giovanni Battista Borra), and fixed him for the voyage. The drawings he made, have convinced all those who have seen them, that we could not have employed any body more fit for our purpose. As a matter of fact the success of the book (published in English and French) resided in its illustrations based on drawings by Giovanni Battista Borra (you may wish to see some of them - external link). The discovery of Palmyra and of its monuments inspired painters (Gavin Hamilton - external link) and architects (Robert Adam - see the ceiling he designed at Wynn House which was based on that of the Temple of Bel - external link).

The ruins of Palmyra were given a second boost in popularity in the early XIXth century when they were visited by Lady Esther Stanhope, niece of William Pitt the Younger. She embarked on a long tour of the Levant to forget a love disappointment; she arrived at Palmyra dressed as an Ottoman officer and she so impressed the local sheiks that she was acclaimed Queen of Palmyra; the following is the account of the event in the American Railroad Journal (1835): It was at this last station (Palmyra) that numerous tribes of wandering Arabs, who had assisted her in visiting these ruins, united around her tent, to the number of forty or fifty thousand, and charmed with her beauty, her grace and her magnificence proclaimed her Queen of Palmyra and delivered firmans (edicts) to her, by means of which it was agreed that any European, protected by her, might come in safety to visit the desert and the ruins, provided he engaged to pay a tribute of a thousand piastres.

Palmyra became a popular destination for western travellers; Philip Van Ness Myers extensively described its ruins in Remains of Lost Empires which was published in 1875. He was professor of history at Cincinnati University and his books had a wide circulation as he knew how to intrigue his readers: Doubtless many a weary traveller, as the city rose upon the desert, looked upon all this grandeur, flitting in the quivering air along the horizon, as only another illusion of the mocking mirage. In its closing history it indeed looms up, and then disappears, like the phantom of the desert.; the book indicates also the initial steps taken by the Ottoman government to protect the site and its visitors:... owing to the isolated situation of these ruins, lying in the midst of the Syrian desert, entirely out of the line of modern caravan routes, they have been seldom visited by travellers. The exorbitant blackmail exacted by the Bedawin has also, till quite recently, been a serious obstruction to such an undertaking. But a few years since the Turkish government, finally aroused to a sense of the strategic importance of the control of the springs of Palmyra in dealing with the Arab tribes dependent upon those fountains, established a garrison there; so now the ruins may be visited, from Damascus, under the protection of a Turkish escort.

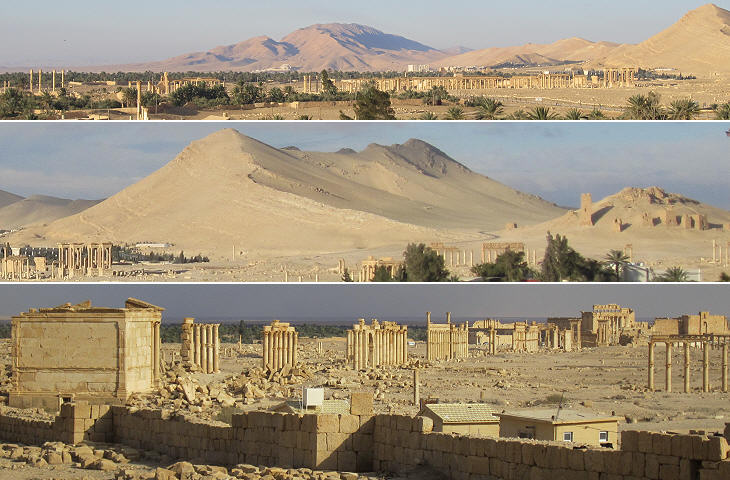

The oasis of Palmyra is located almost midway between the Orontes River, which empties into the Mediterranean Sea, and the Euphrates River, which empties into the Persian Gulf; the climate of the city is not completely dry: snow and hail are not uncommon in winter and the oasis is surrounded by steppe rather than by sand dunes. The name of Palmyra is thought to be a translation of Tadmor, meaning palm in Aramaic; Tadmor is the name Syrian authorities have given to the modern town near the archaeological site.

According to the Bible King Solomon gave importance to the oasis of Palmyra and he established a caravanserai there (built Tadmor in the wilderness - II Chronicles 8:3-4 ), but not all archaeologists agree on Palmyra being the Tadmor of the Bible. The oasis was not located on a traditional main route between the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf; to the north of Palmyra the Euphrates River which was navigable from Birecik to the sea, provided merchants with a safe route and to the south there were other popular trade routes across today's Jordan and between the Gulf of Aqaba in the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf.

Biblical Tadmor disappeared from chronicles and historical accounts until the Ist century BC when the Romans established firm control over Syria; in 64 BC Pompey deposed the last Seleucid king and founded the Roman province of Syria. At that time Palmyra was probably an encampment rather than a town, because when Mark Antony moved towards Palmyra to sack it, the inhabitants fled into the desert with all their goods and the Roman general found the site empty.

Palmyra became a veritable town when the Romans implemented a long term strategy for reducing the control nomadic herdsmen had on the steppe between Mesopotamia and Syria; they favoured the expansion of farming by assigning land to the veterans; they built a series of small forts to control the movements of the nomads; they undertook expeditionary campaigns to retaliate for raids on farms and towns. In this frame of improved security a straight trade route between Syria and Mesopotamia through the oasis of Palmyra became viable. From inscriptions it appears that merchants from Palmyra were present in ports on the Persian Gulf and that they organized caravans there which reached their city; at Palmyra the goods were sold to merchants from major cities of the Roman Empire such as Antioch or Apamea. Palmyra therefore was not just a resting place for caravans, but a major trading centre which offered many opportunities for enrichment. Syrian authorities are keen on asserting that the inhabitants of Palmyra were Arabs; it is a not very meaningful statement: Palmyra from a cultural viewpoint was divided between the influence of the Greco-Roman world and of the Parthian (Persian) one. Palmyra had monuments similar to those of many other cities of the Roman Empire, but its inhabitants wore (at least for their funerary statues) ornate Persian dresses (embroidered tunic and trousers) and were known for being skilled archers (similar to the Parthians).

The prosperity of Palmyra depended very much on the political relations between the Romans and the Parthians; it was damaged by the war waged by Emperor Trajan and it had a long period of growth after Emperor Hadrian signed a lasting peace; the emperor himself visited Palmyra in 129 AD and added his name to it (Palmyra Hadriana); he also granted special privileges (free town) which were probably more of a fiscal nature than of a political one.

The major part of the monuments of Palmyra were built or completed between the reign of Emperor Hadrian and that of Emperor Septimius Severus. Overall during this period there was a balance of power between the Romans and the Parthians; things changed when the Arsacid dynasty which ruled the Parthian Empire was replaced by the Sassanid dynasty; Shapur I, the second member of this dynasty, followed an aggressive policy of expansion and he waged several successful wars; in 244 Emperor Philip the Arab agreed to pay an enormous amount of money in return for a peace agreement and in 260 Emperor Valerian was taken prisoner by Shapur. This period of Roman history is known as the Military Anarchy because of the many emperors who reigned for only a few years.

The Sassanids were eventually defeated and forced to abandon all their conquests owing to the intervention of Odaenathus, chief of Palmyra, who was rewarded by Emperor Gallienus with the title of totus Orientis imperator, a sort of imperial representative for the eastern part of the Empire; Odaenathus was killed by a nephew in 267; his wife Zenobia, building upon the title given to her husband, declared herself Queen of Palmyra, by this intimating she controlled all the Roman territories in Asia and Egypt, and even ruled as Augusta (Empress) on behalf of their young son; for a while the Romans did not react, but eventually Emperor Aurelian in a series of battles defeated the armies sent by Zenobia and finally conquered Palmyra; the queen escaped, but she was captured and brought to Rome. The name of Zenobia became strictly associated with Palmyra: Palmyra's history possesses a tragic interest, and the name of a woman lends to it a glow of romance. A tragic interest, we say, for although Palmyra enjoyed for a period imperial favour, still her own ambition and the envy of Rome rendered her at last the Carthage of Asia; and we speak of romance, because the story of Zenobia, the gifted and beautiful "Queen of the East," is a large part of the city's history. (P. V. N. Myers - introduction to the description of Palmyra). Zenobia was portrayed by many modern artists (see a statue by Harriet Hosmer - external link) and she is celebrated in Syrian bank notes and in the name of many Syrian restaurants throughout the world.

Emperor Diocletian placed a Roman garrison on the former site of Zenobia's palace; Palmyra declined into a provincial town as the continued wars between the Romans (and after them the Byzantines) and the Sassanids impoverished both empires; the town slowly slid into obscurity; it was probably completely abandoned in the early XIIIth century when the Mongols invaded the region.

The image used as background for this page shows a typical decorative motif (rosettes) of the monuments of Palmyra. Go to: Temple of Bel Colonnade Other monuments Funerary monuments Map of Syria with all the locations covered in this website     |